Why are ethnic Chinese leaving South Korea in their thousands?

- The Chinese diaspora – or ‘huaqiao’ – in South Korea has dwindled to less than 20,000, prompting warnings that the community faces ‘extinction’

- Many blame lingering legal restrictions and prejudices that date back to the 1960s

When Ma Jian-xian and his wife converted a cattle shed in a suburb of Seoul into a modest restaurant specialising in pork bone soup in 1989, they had just one customer on their first day of business.

But within a few weeks hundreds of people were queuing up to taste the couple’s speciality dish, known locally as “pyeo haejang guk”. Today, nearly 30 years later, the success of that dish has served the couple well. Ma, now 68, owns assets worth more than US$10 million.

“You may call it a successful China-Korea joint venture,” says Ma as he explains that his Korean wife had adapted a recipe used by his Chinese mother.

It’s the sort of rags-to-riches tale that has inspired countless entrepreneurs among South Korea’s Chinese diaspora – or huaqiao – over the years, but success stories such as Ma’s are becoming far less common. In recent decades the huaqiao population has dwindled from 40,000 people in 1970 to just 18,000 as of last year (a figure that does not include the estimated one million short-term contract workers from mainland China who are employed at places such as restaurants, factories and construction sites).

As Kuo Yuan-yu, the secretary general of the Chinese Residents’ Association in Seoul, puts it: “South Korea is the only country in the world with a huaqiao community facing the danger of extinction.”

Many huaqiao blame the situation on lingering legal restrictions and prejudices that were introduced and stoked by authoritarian governments in the 1960s and 1970s and have never been fully addressed.

In Ma’s case, a combination of his wife’s culinary skills, his acumen for sales, and a secret ingredient or two in the broth meant they could overcome such obstacles. “My Chinese mother-in-law was good at making broth from the pig bones disposed of by a restaurant where her other son was working,” Ma’s wife Kwon Ok-sang recalls. “I took her recipe for this broth and added doinjang [fermented bean paste], vegetables and Korean condiments to make pyeo haejang guk.”

Ma spread the word by handing out coupons giving 50 per cent discounts to taxi drivers, who then told their passengers and the restaurant’s success snowballed. Today, the Wondanghun restaurant in Goyang City is a patented brand and Ma and his wife have built a large real estate portfolio.

THE BAD OLD DAYS

Life was much tougher for Ma’s parents, who left Shukwang county in Shandong province, mainland China, in the 1930s. When they arrived in Korea, the whole peninsula was under Japanese colonial rule.

It took them decades of work as landless farmers to save enough money to buy a 6,600 square metre plot but even when they did so they had to register it under the name of some Korean friends because back then, in the 1960s, foreigners were not allowed to own land.

A decade later, one of the Korean friends died and his children claimed the land as inheritance. Ma’s parents lost half the land in the ensuing court battle that Ma believes led to his father’s death soon after.

Restrictions and prejudices against the huaqiao intensified under the authoritarian rule of presidents Syngman Rhee in the 1950s and Park Chung-hee in the 1960s and the 1970s.

In 1950, Rhee’s government barred foreigners from using warehouses at ports as part of a campaign to curb imports of foreign goods and encourage domestically produced goods.

This measure hit the huaqiao hard as many were merchants and traders. Many went bankrupt, while others sought refuge in the restaurant business.

A further blow came in 1962 when Park Chung-hee, who had seized power through a military coup the previous year, banned the ownership of land by foreigners, forcing many Chinese to sell at dirt cheap prices and give up farming entirely. In 1970, the restriction was eased and foreigners were allowed to own up to 165 square metres of land per person for business and 661 square metres for a house.

Even so, as Kuo of the Chinese Residents’ Association, notes: “This was barely enough to open a Chinese restaurant with four or five tables.”

According to Kuo, the Park government had “feared the huaqiao would expand their economic power and emerge as a potent economic force, as in Southeast Asia”.

When the Park government was staging a campaign to reduce rice consumption and increase that of barley and wheat to cope with rice shortages in 1970, authorities singled out Chinese restaurants and banned them from selling rice-based dishes. Chinese restaurants were also subjected to tight food price controls and were taxed heavily. As a consequence, hundreds of Chinese restaurants folded and moved to the United States.

The land ownership restrictions remained in force until 1999 when the Asian foreign exchange crisis hit and South Korea went in search of foreign capital.

HOME IS WHERE?

Most of the Chinese diaspora in South Korea identifies with Taipei rather than Beijing, but when they travel abroad matters can be complicated because in most cases their ancestors came from Shandong province on the Chinese mainland and they may have no direct relatives living in Taiwan – a requirement for getting a full Taiwanese passport. Instead, Taipei issues them a type of passport that confers only limited privileges.

“This is particularly problematic when our children employed by companies need to travel abroad for business purposes,” says Kuo. “In reality, it is next to impossible for our children hired by companies here to live without acquiring South Korean citizenship.”

Even Ma, who has both Korean citizenship and a Taiwanese passport, has encountered problems. When he travelled to Taiwan two years ago, immigration automatically granted his wife a 90-day visa on the grounds that she was Korean, but kept him behind to fill out more forms.

There are signs things are getting better. In South Korea, prior to 2002, huaqiao had to renew their residence permits every three years. Now the permits last up to 10 years.

Even so, many Chinese in the country say that even with stable jobs and incomes they are unable to borrow from banks and are blocked from accessing the low-interest housing loans so popular with Koreans.

HOPE FOR THE FUTURE?

Problems such as these have encouraged many huaqiao to leave the country, a trend that is highlighted in schools.

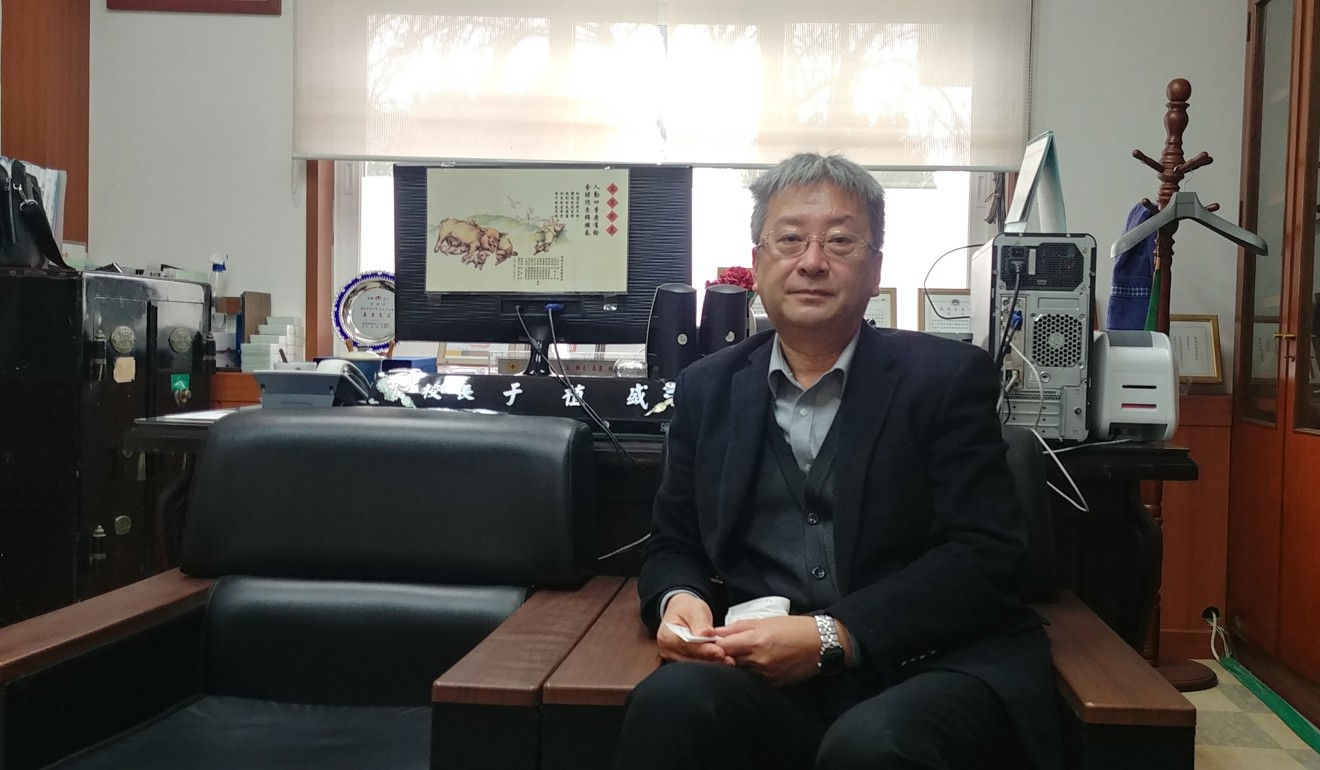

Woo Sik-sung, who heads a Chinese school in Seoul, said there were now just 400 pupils, down from a peak of 2,900 in 1970.

“We actively invite students from mainland China to make up the shortfalls. One third of my students are currently from mainland China,” he says.

“Aside from free textbooks provided by the Taiwanese government, we have to rely entirely on tuition fees [the school charges US$3,990 per year per student] and private donations to keep afloat.”

There are bright spots – last year a benefactor donated US$800,000 that meant the school could undergo long-overdue renovation works – but many see the overall climate facing huaqiao as stifling and oppressive.

“There is nothing like the huaqiao in South Korea. We are not taken care of by either [mainland] China or Taiwan or the host country,” says Kuo of the Chinese Residents’ Association.

Jiang Jia-shang, a spokesman for the Taiwan Representative Office in South Korea, says Taipei is aware of such complaints.

“We’ve been conveying their complaints to Taipei but it will take time to amend laws and regulations to address their problems,” he says.

Still, even if such problems can be addressed, as Ma points out, pieces of paper and official documents don’t solve everything.

Holding up his South Korean ID card, Ma says the immigration authorities “gave me this ID card on the condition that I only use it and I don’t use the Taiwan passport as long as I am in this country”.

“But I am proud of my roots as a Chinese and I still feel like a Chinese, even if I was born and raised here.”