Can faster conversion of farmland provide a solution to Hong Kong’s housing problem?

Converting farmland to residential seen as feasible solution for a government starter home scheme in partnership with private developers

The 20-minute journey by minibus from the MTR’s Tai Po station traverses the narrow two-lane Tung Tsz Road, passing abandoned vehicles on both sides of the road, reaching a wooded area dotted with a small number of villages. The farmland, vacant for more than 20 years and owned by Wheelock and Co, which has taken legal action against the tenant because of containers and construction waste allegedly being stored there without the group’s consent.

Yet this remote spot could be where Hong Kong’s young families are finally able to afford their own home in what could become the city’s biggest private-public housing estate.

The farmland has come under the spotlight after Wheelock sought government approval to convert it into residential use for a 2,705-unit housing estate.

“There are numerous agricultural sites in Tai Po, Yuen Long and Tuen Mun in the hands of developers that have been left idle for 30 or 40 years,” said Lee Wing-tat, former chairman of the Democratic Party and now chairman of think tank Land Watch.

The application process to convert farmland into residential land, some of which is zoned as green belt under the city’s environmental protection ordinance, could involve more than 10 government departments. “Besides land premium negotiations, approvals by different departments including the town planning board will be a pain for developers,” he said.

Even the biggest developers find it too difficult. Henderson Land Development, Hong Kong’s

biggest farmland owner with 44.9 million square feet of land, hasn’t been able to to satisfy town planning board requirements for the past 20 years for its private housing estate in Nam Shang Wai private housing estate, a wetland north of Yuen Long.

Neglected for decades, vast tracts of farmland in different parts of the New Territories have suddenly been thrust into the limelight amid calls for Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor’s new administration to increase the supply of subsidised housing to help contain runaway home prices.

When the city’s new chief executive unveiled her “Starter Homes” scheme on September 7 to help young families climb on the property ladder, the idea was quickly followed by numerous calls for the government to team up with private developers to build mixed private-public housing.

Adding momentum to the debate on the housing shortage in Hong Kong, already the world’s most expensive urban centre, is the new housing minister Frank Chan Fan, who has also floated various ideas to provide homes to needy families, including container homes and authorised subdivided rental flats.

But market watchers believe conversion of farmland for homes could provide a key long term solution for Hong Kong’s housing problem, whereas other alternatives are just seen as interim measures.

“[Farmland conversion] is certainly one of the easiest and fastest ways to increase land supply for housing and has the advantage of scale in that the agricultural holdings in question are very large and could produce a significant supply of new housing,” said Nicholas Brooke, chairman of Professional Property Services.

“It also has the advantage that the process...is totally within the control of the government [through] the Lands Department,” he said.

Given the mounting opposition to land reclamation and unwillingness by many to give up country parks for housing, analysts believe farmland conversion would be a feasible solution to support Lam’s “Starter Homes” scheme via partnerships with private developers.

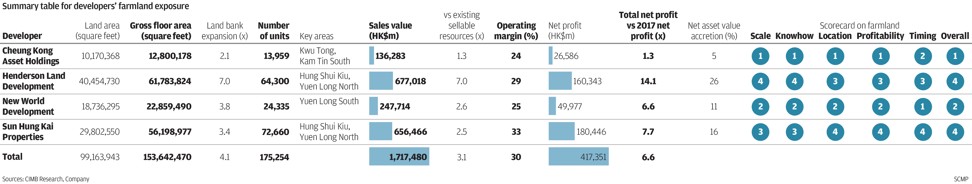

The four key farmland holders are Henderson Land Development, Sun Hung Kai Properties, New World Development and Cheung Kong Property (Holdings), which was renamed CK Asset Holdings on September 15.

“This potential supply represents about eight to nine years of housing demand in Hong Kong and could solve the housing problem if the government speeds up the approval process of farmland conversion,” he said.

Cheng estimates that after the farmland is rezoned as residential land the new housing projects could be launched within two to five years.

“We estimate that this could translate into HK$10 billion to HK$50 billion in annual sales starting from 2020, depending on the developer,” he said.

Brooke believes a “carrot and stick” approach could accelerate the land use conversion and quicken the pace of supply.

“The incentive [carrot] has to be a premium adjustment to reflect the requirement that the developer provides a certain percentage of affordable units, say 35 per cent within the overall of development which will be priced differently and only offered to certain pre-qualified purchasers,” he said. “The stick is the prospect of resumption if the developers fail to respond to the urging from the Chief Executive.”

Brooke said several major developers have indicated they have agricultural sites available for this new initiative. Wheelock Properties, a subsidiary of Wheelock & Co, has said it was willing to set aside 40 per cent of its proposed residential project on 860,000 square feet of farmland in Tung Tsz Road – equivalent to half the area of Victoria Park – for affordable homes.

South of Wheelock’s proposed project, Henderson Land has filed an application to build a 795-unit private-public housing estate at Cheung Shue Tan, near Sino Land’s upmarket Providence Bay. The developer has proposed setting aside 36 per cent of the project, or 289 units, for subsidised housing.

Carrie Lam’s home starter scheme for young families who cannot afford private housing but earn too much to qualify to rent public flats will be outlined in her maiden policy speech on October 11.

Developers who have openly supported the scheme include Sun Hung Kai Properties chairman Raymond Kwok Ping-luen and Adrian Cheng, executive chairman of New World Development.

But whether these housing solutions will be able to contain runaway prices is an open question.

While the policy of converting farmland to residential use will help relieve demand pressure, the number of units available in the initial years would be no more than 10 per cent of the current annual supply each year, according to Lau Chun-kong, international director at JLL in Hong Kong.

The government’s annual target is about 46,000 units – 18,000 private homes and 28,000 subsidised ones.

Lau said the government needs to be more proactive in handling conversion applications, including provision of the required infrastructure and the approval process for a public-private partnership.

Lee of Land Watch agreed, adding that land premiums should be reduced if applicants require heavy investment in infrastructure.

“For instance, if the government asked for a HK$1 billion land premium to convert farmland into residential but the developer needed to spend HK$500 million to build a four-link road to access the site, it is fair to reduce the premium to HK$500 million,” Lee said.

He said the challenge faced by the government was to establish a fair and transparent system when assessing land premiums for developers taking part in mixed private-public projects to minimise criticism.

“[Developers] have to show their projects will have greater benefit to the general public than to self interest. For instance, allocating 60 to 70 per cent of flats as affordable homes to be built on farm sites that require taxpayer money to improve roads and other infrastructure,” he said.