Hong Kong’s home prices are the world’s highest. Can the city fix it?

A housing market that has become the world’s least affordable seven years in a row now stands atop the list of policy imperatives of the city’s chief executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor.

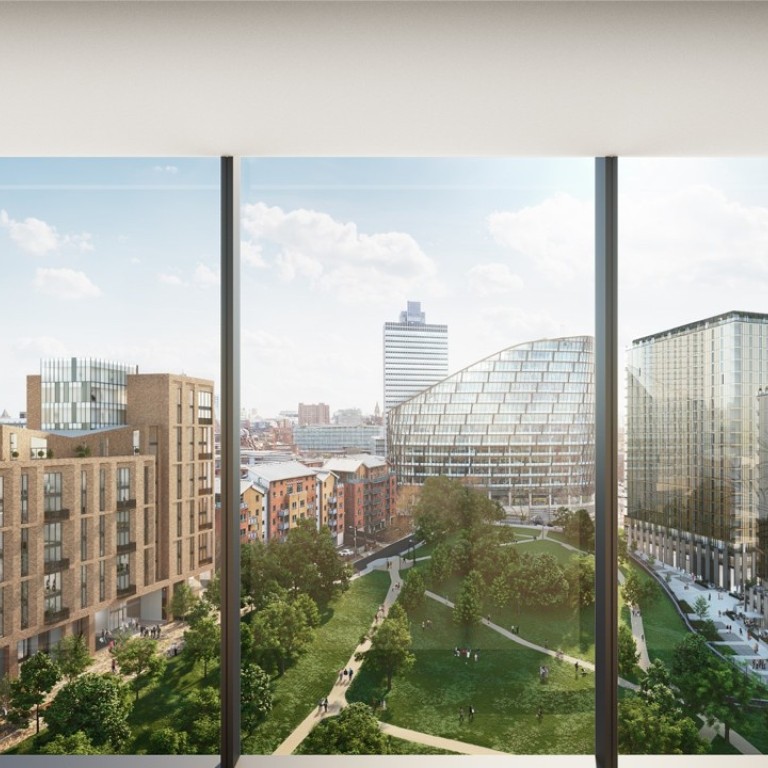

When Far East Consortium International, a Hong Kong developer valued at one-36th of the city’s biggest builder, won a tender to build 10,000 homes in Manchester, it did so neither by the heft of its order book, nor by the size of its financial war chest: it was a comprehensive master plan that beat out five global bidders in an open tender.

The £1 billion (US$1.3 billion) project - equivalent nearly to Hong Kong’s Taikoo Shing township in size and scope - will be jointly developed with the Manchester City Council over the next decade, emphasising on design quality, sustainability, open space, with walking and cycling routes. The city council described the plan, which cover 120 hectares (296 acres) of an area littered with industrial sites, as the most ambitious housing-led regeneration project ever undertaken in Manchester.

The success by Far East in punching above its weight is one example of how developers can balance their shareholders’ interest with social needs to arrive at a happy medium, where homes can be built with quality, but at prices affordable by medium-income families.

The example is particularly pertinent for Far East’s home base in Hong Kong, where a housing market that has become the world’s least affordable seven years in a row now stands atop the list of policy imperatives of the city’s chief executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor.

Since 2003, home prices in Hong Kong have soared 430 per cent, making the city the most expensive place in the world to buy a home among 406 urban centres tracked by the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey.

The median price for a typical Hong Kong flat is HK$5.42 million (US$692,700) in 2017, at least 74 per cent higher than a comparable apartment in uptown New York, 18 per cent more than London and 148 per cent more expensive than Tokyo, Demographia said.

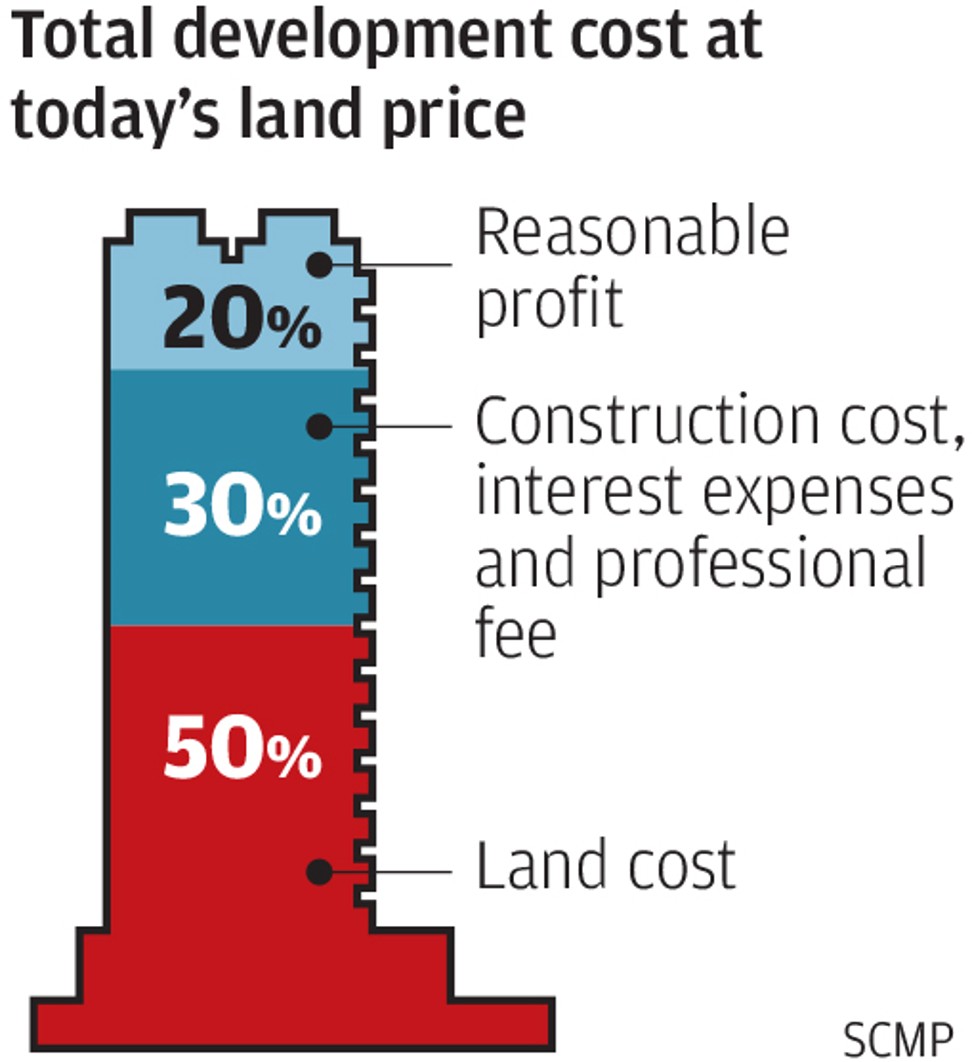

A major contributor to the exorbitant housing price is Hong Kong’s high land cost. That could make up between 60 per cent to 70 per cent of the total project cost, more than double the 20 per cent to 30 per cent range seen outside Hong Kong, said Far East’s managing director Chris Hoong Cheong Thard.

The 45-year old company speaks from experience, as it has found itself being priced out of its home turf in the last two years in its quest for land parcels for building homes. It hadn’t won a single parcel of land since 2016, compared with its previous batting average of winning one plot out of every six on offer.

“The real competition is cash when bidding for government land in Hong Kong,” said Hoong. “Small developers are hardly able to gain access to any sizeable development.”

What’s changed was the emergence of deep-pocketed developers from mainland China in the last two years, such as the HNA Group, which had no hesitation in bidding 50 per cent above market valuation to grab land. HNA paid HK$27.2 billion to buy four plots of land from the Hong Kong government at the former Kai Tak airport site over four months last year.

That has forced Far East to hone its design concepts instead of its financial heft to expand its order book. The company is now developing the biggest residential project in the central business district of Melbourne in Australia.

Highest-bidder-wins-all is no longer the mainstream land sale policy in most countries, especially for plots located in city centres, said Christopher Law, founding director of Oval Partnership, a Hong Kong architecture firm. The UK government, for instance, awards tenders to contractor who can check several boxes, including economic value, job opportunities, and the promotion or arts and culture.

The city’s former Marine Police Headquarters in Tsim Sha Tsui was developed into the 1881 Heritage commercial complex in 2003 by tycoon Li Ka-shing’s CK Asset, in a HK$352.8 million tender. In 2007, the new cruise terminal in Kai Tak was awarded to Dragages based on an assessment that was 70 per cent based on quality, and 30 per cent based on premium.

But for now, public tender based on the bidding price is still the most appropriate policy because it is “fair, just, competitive and transparent to dispose of land in an efficient manner,” the Hong Kong Development Bureau wrote in a December 15 reply to the South China Morning Post.