Japanese designer Sou Fujimoto on 'blurring the boundaries' between nature and architecture

Quirky project by the award-winning Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto shows his passion for 'blurring the boundaries'

Japan's fascination with toilet design is legendary, so it is perhaps no surprise that one of Sou Fujimoto's favourite projects is a tiny public toilet within a landscape garden next to Itabu station in Ichihara city, Chiba.

The Tokyo-based architect was in Hong Kong recently for Business of Design Week, where his intriguing design solution addressing the timeless issues of personal privacy, public space and nature drew spontaneous applause.

"That was a funny project," he said with a laugh. "The requirement was for a public toilet on a site that looked like a natural field. A public toilet is interesting because it is both very private and public at the same time.

Fujimoto has received numerous awards, including The Architectural Review AR Award in 2006 for his Children's Centre for Psychiatric Rehabilitation in Hokkaido, Japan; and another AR Award in 2007 for his House O, an ultra-contemporary weekend retreat two hours' drive southeast of Tokyo, where he designed the living and dining areas, a bedroom, study and bathroom in one continuous tree-like space that maximises the site's panoramic sea views.

"Working with diverse scales is very exciting for me," said Fujimoto, who was born in Hokkaido and moved to Tokyo to study.

"In Japan young architects have a great opportunity to start work on small homes, but I also enjoy working outside of Japan in different countries and with different programmes." In 2012 Fujimoto was awarded the Golden Lion for his participation at the Japan Pavilion at the International Architecture Exhibition - La Biennale di Venezia.

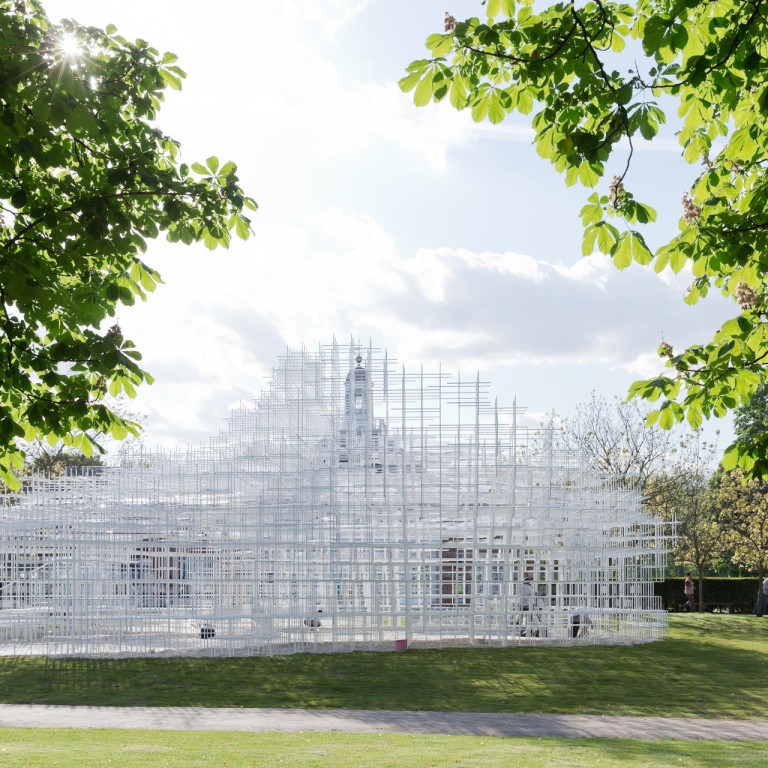

And last year he won fame throughout the United Kingdom thanks to the phenomenal success of his summer pavilion for London's Serpentine Gallery. Here, in an effort to "create something that would melt into the green" of Kensington Garden's lush landscape, he created a delicate latticework cloud of white-painted 20mm-thick steel bars. The grid - a recurring theme in his work - varies in density and has circles of transparent polycarbonate to protect it from rain.

Although unapologetically artificial, the ethereal structure perfectly captured Fujimoto's long-held preoccupation with creating something "between architecture and nature".

"It is a very simple and fundamental concept," he said. "Nature and architecture, outside and inside, are always blurred. This is not a superficial Japanese style - it is more of a fundamental concept."

Sou Fujimoto Architects has several projects in China including a museum in Shanghai and an art gallery in Guangzhou.

He laughed again when asked how this experience compares with Japan, where contractors are famously efficient.

"Ten years ago it was quite different, but now there are many architects working in China and the architectural quality is getting to be very good. [Japanese architect] Kengo Kuma has many architectural projects there and he has done very well in controlling quality so it is possible to achieve."

He said: "In Japan we work with the contractors very easily. Even during the process we can discuss and update where necessary but in China I have found that on construction sites the designer can't touch anything."

Fujimoto said working closely with innovative engineers had proved critical in achieving innovative designs.

"Structural issues can restrict architecture, but for me these restrictions inspire and stimulate me to make things. I like to push these boundaries. It is not about fighting, but dissolving the boundaries."

The designer still prefers to use what he calls "simple means" such as sketches and models at the creative stage of a new project. His fluid sketches usually resemble loose organic lines hinting at an architectural form instead of highly structured drawings. This process, he explained, allows the architecture to emerge or be nurtured.

"Sometimes the ideas are beyond possibility for that project, but the concept will be there in my mind for a long time until a time comes when I can recreate it," he said.

"Every stage of architecture has its own exciting part, but for me the best point is the starting point when I can think freely about the potential of the project. That is when I think I can do anything."