A look back at 115 years of letters to the editor at the South China Morning Post

Empires rise and fall, governments come and go, economies soar and sink, but some reader gripes are eternal

The most important people for a newspaper are always its readers. The relationship between the two parties has been transformed as media companies reinvent themselves for the digital age. However, the fundamental dynamic remains: it is never an exaggeration to say that without the readers, there would be no newspaper.

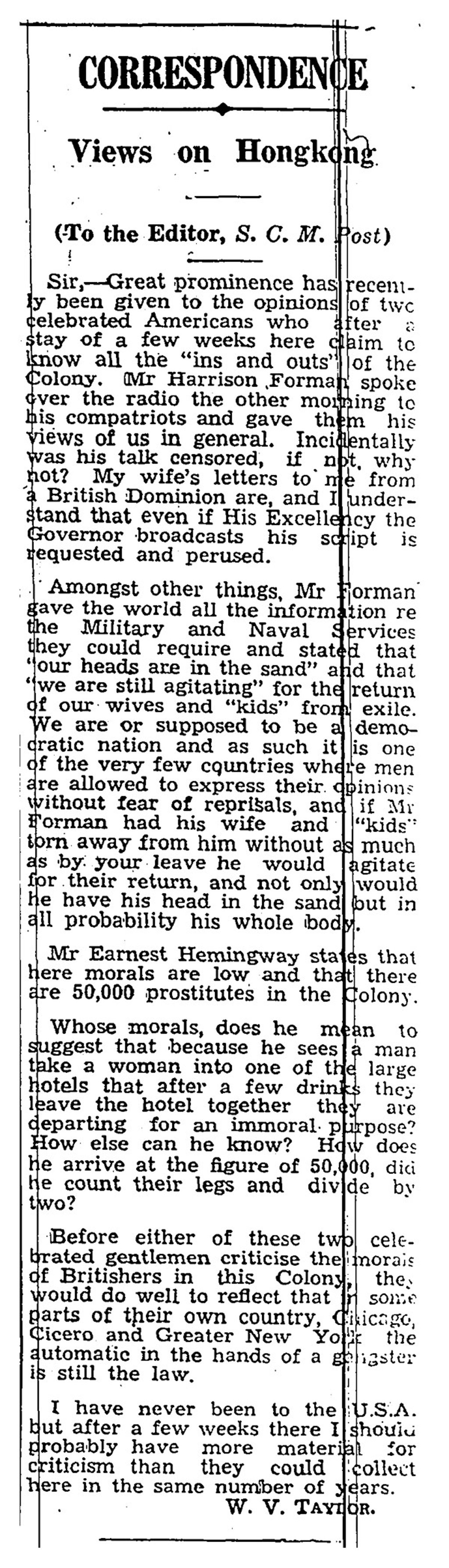

Since it was founded in November 1903, the South China Morning Post has been running letters. They were published as “Correspondence” for years, until the section was renamed “Letters to the Editor” on April 11, 1967.

To date, the Post is the only newspaper in Hong Kong running a letters to the editor page.

The first batch were published on November 25, 1903. The writer of one letter that day titled “China railways” called for early construction of the Kowloon-Canton Railway connecting Hong Kong with Guangzhou.

“If not, then we shall, of a surety, be behind all the important cities, both in the north and south,” said the writer, using the pseudonym “progress”.

His plea bears heavy resemblance to warnings more than 100 years later. In recent years Hong Kong officials have repeatedly cautioned that the city risked being left behind without construction of the latest rail link to Guangzhou.