Why do Hong Kong, China and Taiwan have separate teams at the Olympic Games?

- Taiwan have marched under the name of ‘Chinese Taipei’ since the 1984 Olympic Games after a long political battle for recognition with the mainland

- After the 1997 handover, Hong Kong are known as ‘Hong Kong, China’ in international sports under ‘one country, two systems’

As the Hong Kong team marched into the Maracana Stadium in Rio for opening ceremony of the 2016 Olympics, someone in the crowd asked: “Why does Hong Kong have a separate team to China?”

A generation ago, that would never be asked because the memory of the former British colony’s handover to China in 1997 would be fresh, along with the deal between the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and China that Hong Kong would be allowed to compete as a separate sporting entity under “one country, two systems” and under the name “Hong Kong, China”.

Mainland and Hong Kong athletes who win gold would stand on the top podium to the Chinese national anthem, while the Olympic anthem and special flag is raised for Taiwanese winners. China’s official Olympic history goes back to 1932 in Los Angeles, while Hong Kong’s first Olympics as a British colony was in Helsinki in 1952 when China also made its first appearance under communist rule. Taiwan’s history is a bit more complicated, having represented “China” for two decades while mainland China boycotted the Games.

In the beginning

This special arrangement for multiple China teams is a product of the twists and turns of the country’s modern history, a legacy first of colonialism in China, and then the Chinese civil war.

Its evolution traces the decades-long battle between Beijing and Taipei to secure international recognition as the legitimate representative of “China” – and how Beijing ultimately came out on top.

There are historical disputes over when exactly China was first invited to participate in the Olympic Games. One popular tale holds that it was invited to attend the inaugural games in Athens, Greece, in 1896, but the then-ruling Qing court did not understand what was meant by the term Olympics, and dismissed it.

Other historians dispute this, saying that the Chinese National Olympic Committee was only recognised by the IOC in 1922, and was first extended an invitation to send an observer to the 1928 Games in Amsterdam.

Nonetheless, it would take over three decades since the first Olympic Games for China to send its first official delegation.

The 1932 Summer Games: China’s first Olympian

Through the help of an 8,000 silver dollar donation from northern warlord Zhang Xueliang, China fielded a six-person delegation. Although Liu failed to make it past the preliminary races, he went down in history as the first Chinese athlete to ever compete at the Olympics.

The outpouring of pride created by Liu’s journey pushed the ruling Republic of China government to turn out big for the Games that followed. Sixty-nine athletes went to the 1936 Berlin Games, where pole vaulter Fu Baolu became the first Chinese athlete to ever make the finals in an event.

A smaller delegation also joined the 1948 Games in London, although not a single athlete made the finals – and the group had to borrow money to finance their journey home. It would also mark the last time that a single team would compete on behalf of all of China.

What happened after the 1949 revolution?

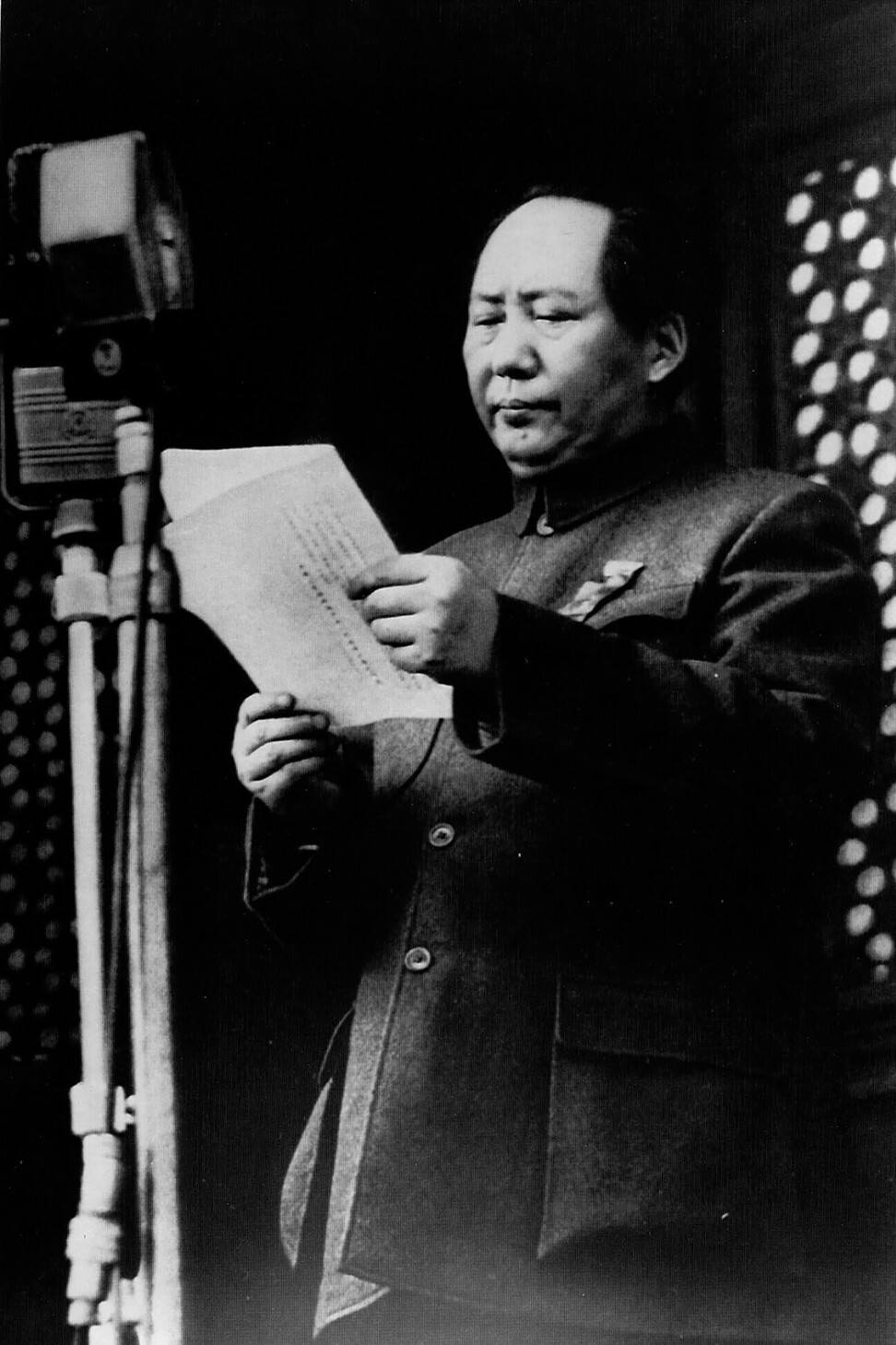

Following the victory of Mao Zedong’s Communist forces in the civil war, and the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, remnants of the ROC fled to Taiwan. This included 19 of the 25 members of the Chinese National Olympic Committee, who reconstituted themselves in Taipei.

Meanwhile, what remained of the committee on the mainland moved its headquarters from Nanjing to the PRC’s new capital in Beijing, now operating under the name All-China Sports Federation.

This marked the start of a decades-long battle between Beijing and Taipei to have their respective committees recognised by the IOC as the sole representative of Greater China.

In the lead-up to the 1952 Games in Helsinki, Finland, the IOC decided to play safe by extending invitations to both parties and delay a final decision on IOC recognition.

Taipei took the decision – and the fact that they were named in the invitation as China (Formosa) – as a snub and withdrew in protest. Beijing, however, did not pass up the opportunity.

The PRC’s first Olympics: The 1952 Helsinki Games

Receiving the invitation only two days before the Games were set to start, Beijing quickly put together a delegation of a basketball and football team, as well as swimmer Wu Chuanyu. At a meeting on the eve of the delegation’s departure, then-premier Zhou Enlai remarked: “It is a victory for the PRC when its flag is flying at the [Helsinki] Olympic Games. Being late was not our fault.”

Wu ended up being the only athlete to make his event in time, but the PRC’s new national flag was indeed hoisted for the first time ever at the Olympic Village that July. The 1952 Games also marked the start of a new era for the then-British colony of Hong Kong.

The IOC recognised Hong Kong’s Olympic Committee in 1951 and invited them to attend as a separate entity from Britain and Chinese teams. Competing under its own name, Hong Kong fielded four athletes.

Two years of political infighting later, and the IOC finally voted to recognise the All-China Sports Federation as the Chinese Olympic Committee (COC). Nonetheless, Beijing was not yet satisfied.

1956-1980: Beijing’s two-decade Olympic boycott

Despite the apparent victory for Beijing, Taipei’s Chinese National Olympic Committee still retained formal recognition as a member of the IOC. Taipei also received an invitation to join the 1956 Games in Melbourne, Australia, where they would compete under the name “Republic of China”.

Beijing rejected what it called the IOC’s “Two China” policy, leading it to boycott the Games.

Two years later, the COC were ordered to withdraw from 11 international sports organisations that continued to recognise Taipei as a member, marking the start of Beijing’s two-decade boycott of the entire Olympic movement.

From then on, Taipei would serve as the sole representative for China at the Games. Its Olympic committee was forced to rename itself “Olympic Committee of the Republic of China”, while its team competed under the name “Taiwan” until it switched to “Republic of China” in 1968.

Over this period, Taipei set a milestone for Chinese sport when decathlete Yang Chuan-kwang became the first Chinese athlete to ever earn a spot on the Olympic podium, at the 1960 Games in Rome. The Hong Kong team also continued to compete over this period, but failed to produce any medallists.

How did Beijing’s boycott end?

Throughout this time, Beijing’s isolation on the international stage began to gradually recede and countries started recognising the mainland over Taipei, eventually clearing the way for China’s re-entry into the Olympic world.

Support had always been strong among the developing world – in 1963, Indonesia organised and invited Beijing to the “Games of New Emerging Forces” in a deliberate snub to the IOC – but events took on a momentum once Beijing took over Taipei’s seat at the United Nations in 1972.

The true watershed moment came at the 1976 Olympic Games in Montreal, Canada.

Ottawa had established formal diplomatic relations with the PRC six years earlier and, under pressure from Beijing, declined to allow Taipei to continue its decades-long practice of competing under the name “Republic of China”.

Although Ottawa offered a last-minute compromise to Taipei – it could use the ROC flag and anthem at all ceremonies, but still needed to compete under the “Taiwan” label – Taipei boycotted the Games for the first time since 1952. Growing political pressure forced the IOC to act, eventually resulting in the 1979 “Nagoya Resolution” that laid the foundation for the arrangement that has continued to this day.

Why was the 1979 “Nagoya Resolution” so important?

At a 1979 meeting held in Nagoya, Japan, the IOC voted overwhelmingly – 62 for, 17 against, and 2 abstentions – to invite both Beijing and Taipei to the 1980 Winter and Summer Games. Although relations between Washington and Beijing had improved markedly by this time, among those voting against the resolution were both US members of the IOC.

According to the resolution, Taipei’s Olympic committee was to be recognised as a provincial body, and renamed the “Chinese Taipei Olympic Committee”. It could also no longer use the ROC flag and anthem at Olympic events and would have to compete under the name “Chinese Taipei”.

Only three months after the vote, Beijing participated in its first Olympic Games in 28 years at Lake Placid, USA. Twenty-four athletes attended but they failed to win any medals. However, owing to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan, an anti-Soviet bloc that included Beijing chose to boycott the Summer Games in Moscow. Hong Kong also failed to send a team for the first time since 1952.

Taipei boycotted both Games and its status in the Olympics would not be clarified until it reached an agreement with the IOC in 1981. That year, Taipei agreed to the terms of the Nagoya Resolution and would use the new emblem and flag of the Chinese Taipei Olympic Committee at the Games.

When were all three Chinese teams first reunited at the Games?

Taipei’s acceptance of the Nagoya Resolution paved the way for China, Taiwan and Hong Kong to compete at the same Olympics at the 1984 Games in Los Angeles – the same city where China first participated in the Games 62 years earlier.

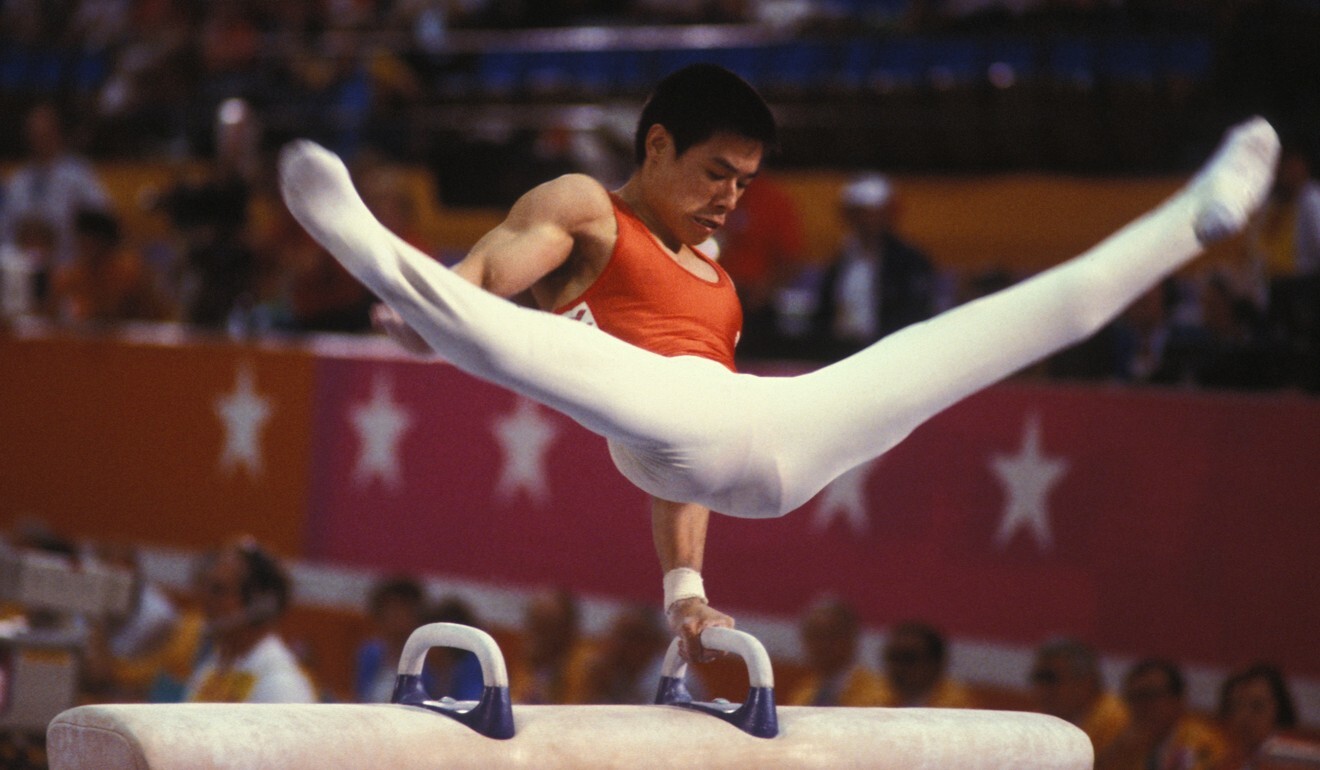

It would prove a historic coming-out party for Beijing. Fielding 215 athletes, the Chinese team took home its first gold medal ever – 15 of them in fact, in shooting, weightlifting, fencing, gymnastics, volleyball and diving.

One notable breakout star was gymnast Li Ning. Li took home six medals including three golds, a record for any Chinese athlete that stands to this day. The women’s volleyball team also defeated the hosting USA team.

The much smaller Taipei and Hong Kong delegations, fielding 38 and 47 athletes respectively, did not fare as well. Only one Taiwanese athlete earned a spot on the podium, with weightlifter Tsai Wen-yee taking home bronze.

The new normal: from 1984 through today

Following its successful experiment in Los Angeles, this special arrangement would remain in place for all subsequent Games, albeit with some modifications along the way.

Taipei realised that while the English name for its Olympic committee was a lost cause, it still had some flexibility with the Chinese translation. It entered negotiations with Beijing, asking that the translation read zhonghua taibei rather than zhongguo taibei, which they thought implied subordination to the COC.

A series of secret meetings were held in Hong Kong to hash out the dispute, and Deng himself finally agreed to Taipei’s translation in 1989. Nonetheless, some media outlets on the mainland continued to refer to the former translation, causing a minor dust-up before the 2008 Olympics in Beijing.

Another dispute arose the following decade, when organisations in Taiwan called on the IOC to allow “Taiwan” to be used at the 2020 Tokyo Games, but the IOC struck it down. Nonetheless, Taipei went on to compete in every Olympics since 1984 alongside the mainland team.

It earned its first gold medals at the 2004 Games in Athens, Greece, in both the men’s and women’s flyweight taekwondo events.

Hong Kong after the handover

Hong Kong’s handover from British to Chinese sovereignty in 1997 also brought a minor change in the formula.

On July 3, 1997, two days after the handover, Hong Kong and the IOC signed an agreement adding “China” to the team’s name, so it would now read “Hong Kong, China”.

Hong Kong’s new flag would be flown, while the Chinese national anthem would be played at all medal ceremonies.