China shines the spotlight on soccer spending spree as the soap opera takes a new twist

The Chinese government has ticked off investors for ‘irrational investments’ in football. But what does that mean?

This phraseology has hung around the vicinity of Chinese football throughout 2017 without the government having ever publicly clarified what it means. Having spoken to several officials associated with football during a recent visit I made to China, I now have a stronger sense of its meaning. Likewise, I have been able to better understand the reasons why some football investors appear to be in the spotlight, whilst others are not.

At the same time, it is felt that companies such as Wanda and Fosun have funded their overseas investment programmes by incurring considerable domestic debt, which in turn has exposed China to significant financial risk. This is problematic as Chinese economic growth has slowed considerably in recent years.

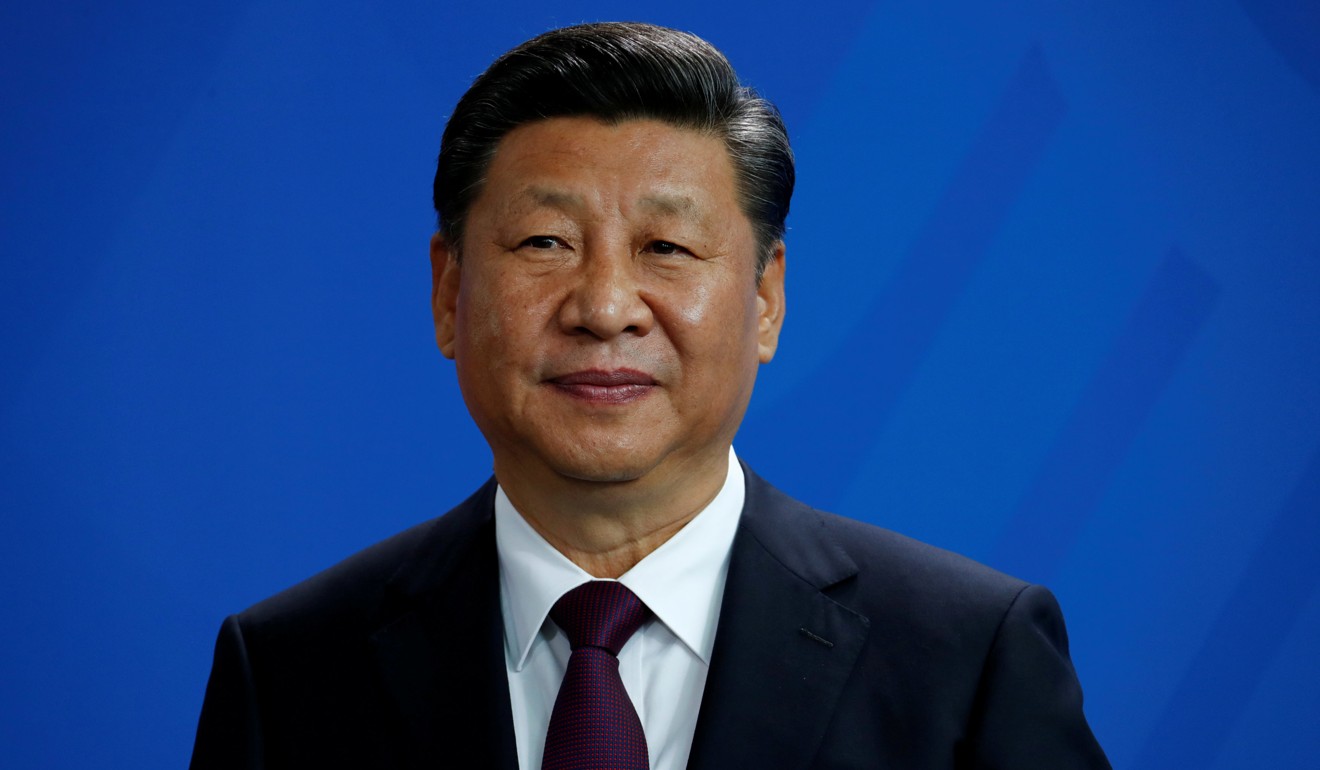

China’s president Xi Jinping has made the eradication of corruption one focus for the legacy of his term in office, and he wants nothing to undermine it. Being accused of activity that may consequently be deemed as ‘corrupt’ is therefore not only deeply concerning for those in positions of wealth or power (they could be imprisoned), it is also publicly embarrassing for them too.

Thus far, Suning has been a largely respectable high street and online electrical retailer. However, the company’s forays into sport have posed some financial challenges for it.

Yet this was not the only chapter of Chinese football’s unfolding financial story. The following week, the CSL announced that 13 clubs face expulsion from the league due to unpaid debts. As clubs have stuttered and stumbled through their responses to the CSL’s request, the sense we are left with is of Chinese football’s wild days of excess being moderated and its clubs being pulled into line by the state, at least for the time being.

With Wanda, Fosun and now Suning all seemingly being monitored by the Chinese government, this raises some interesting questions. Why does Alibaba not seem to be in trouble? How has Zhejiang Luosen so far escaped significant scrutiny? The latter is especially intriguing because, as more modest spenders have been reigned-in by the state, Luosen has taken AC Milan on an extravagant player transfer spending spree.

One is that asset yields on acquisitions undertaken by some investors have been greater than those undertaken by others. Alongside this, companies such as Alibaba have engaged in business development activities that have been more consistent with a ‘China first’ policy; that is, investments at home. Sport industry insiders believe, however, there are other reasons for the state becoming more invasive in its approach to football investments.

The likes of Wanda have spent fast, big and widely on the sport, going way beyond what Xi expected. In government, such autonomy has been perceived to be a growing threat to Xi’s autocracy, especially at a time when the president has otherwise been systematically removing his rivals from important government positions. Similarly, it would appear there are significant divisions within the ruling communist party, with some of the football investors now being investigated or threatened by state apparatus apparently heavily associated with anti-Xi factions.

The English normally refer to things ‘kicking-off’ in the context of players fighting or rival hooligans goading each other. It seems that China is at least having an impact on the world game by reinterpreting the terminology and recasting it as a political (and indeed economic) football.

This piece is published in partnership with Policy Forum, an academic blog based at the Australian National University’s Crawford School of Public Policy.