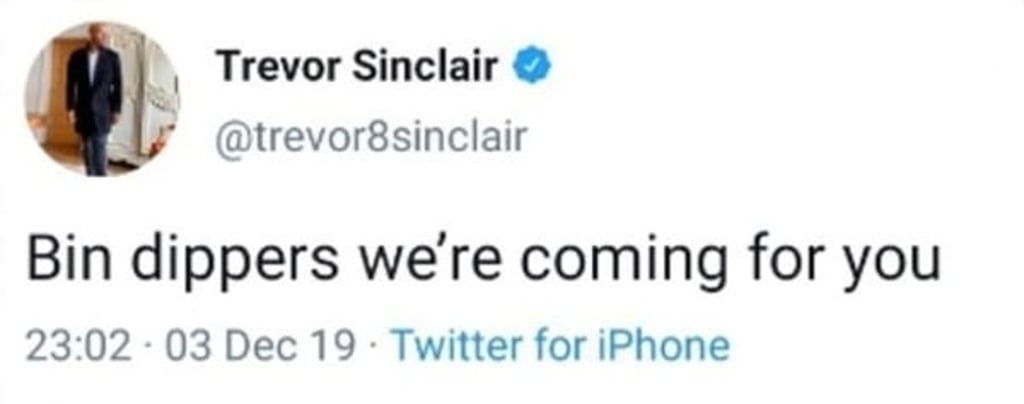

Opinion | Trevor Sinclair’s ‘bin dippers’ jibe shows even poverty is not off-limits in the widespread anti-Merseyside aversion

- The former Manchester City player, who has since apologised for the remark, initially branded those offended ‘so sensitive’

- Sinclair made the comments after a Manchester City midweek victory

Liverpool and Everton supporters are used to being called insulting names. “Bin dipper” is a common form of abuse. This week it was used by Trevor Sinclair, the former Manchester City and West Ham United winger. He wrote the pejorative term for Scousers in a tweet about City closing the gap at the top of the Premier League to eight points after their 4-1 victory over Burnley. “Bin dippers we’re coming for you,” he said.

Sinclair is 46. Old enough to know better. Initially he doubled down, calling those who objected to the insult “so sensitive”. Then, as reality dawned, he apologised, explaining that he is a “working class lad”.

The phrase comes from a terrace chant that developed in the 1970s and 80s. Opposing supporters adapted In My Liverpool Home, a well known song, changing the lyrics. “You look in the dustbin for something to eat,” they chorus, “you find a dead rat and you think it’s a treat ...” It alludes to poverty on Merseyside. So much for Sinclair’s class solidarity.

The city of Liverpool is no longer an outlier in terms of deprivation in the way it was four decades ago. Back then it was visibly poor. Now it is little different to the rest of the United Kingdom. Homelessness has grown hugely across the nation and the sight of people searching through rubbish in desperation is no longer uncommon.

Liverpool and Everton have been at the forefront of football’s attempt to address some of the problems associated with poverty. Both clubs operate food banks where supporters can drop off donations for those who cannot make ends meet. Trent Alexander-Arnold has been especially active in this area and this week the 21-year-old England full back launched Liverpool’s Christmas appeal with a visit to St Andrew’s Community Centre where 25 per cent of the food donated is left before matches at Goodison and Anfield.