Opinion | Tokyo 2020, Kenneth To and Poon Ching-chiu deaths and cancellations dominate Hong Kong sport in 2019

- The deaths of Poon Ching-chiu and Kenneth To overshadow a turbulent year for local sport

- The city’s sporting calendar takes a hit due to unstable political climate, with high-profile events falling victim

Our writers look back at the year just gone and the one ahead.

A tragic year offers lessons for Hong Kong Sports Institute

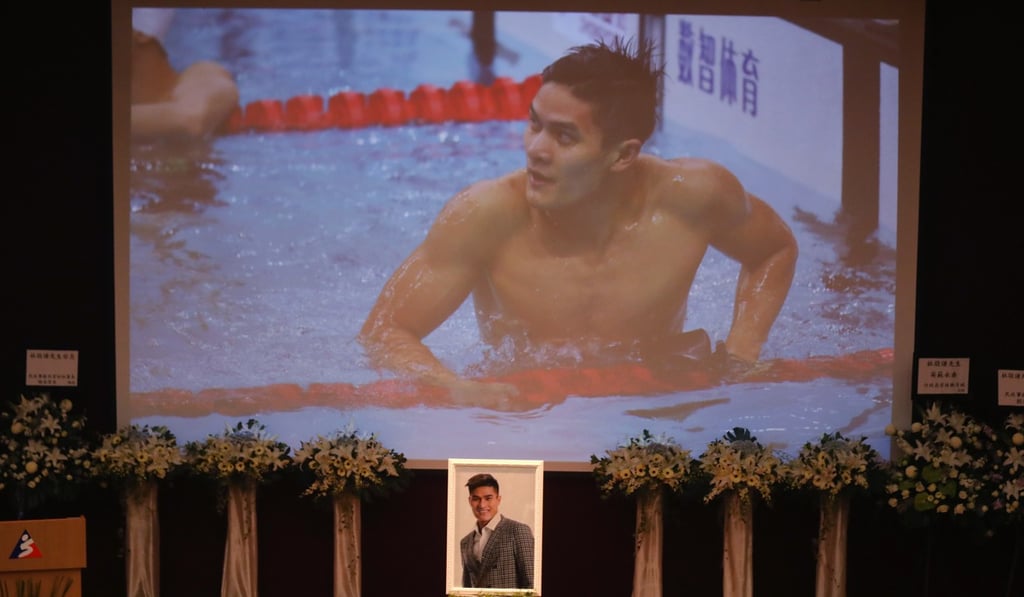

We can’t help but be reminded of the saddest moments of the year with the passing of two elite athletes – swimmer Kenneth To King-him and snooker player Poon Ching-chiu.

Record-breaking To died suddenly at the age of 26 during a training camp in the United States in March. He felt unwell in the locker room after a practice session and was taken to hospital where he later died. He had been undergoing a three-month training programme with the famous Gator Swim Club of the University of Florida.

To had claimed Hong Kong records in 17 events, short and long course, individual and relay, all in less than three years since returning to the place of his birth in Sydney, where he was raised from the age of two.