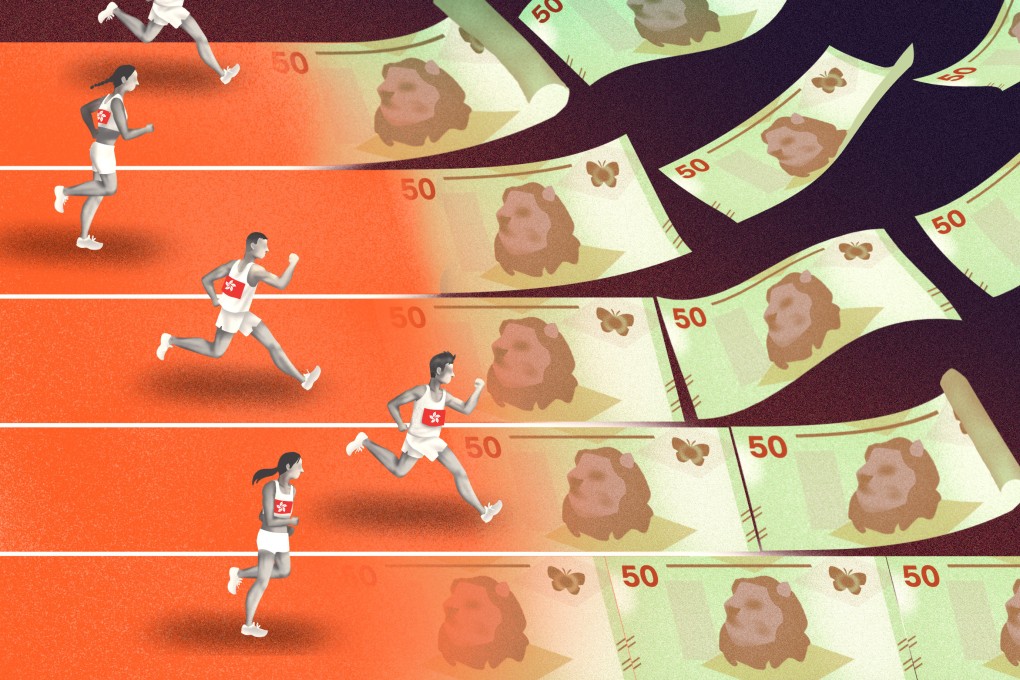

Investment in Hong Kong or wasted billions? Inside the city’s HK$7 billion publicly funded hunt for sporting gold

- As another Olympic year dawns, taxpayers are once again forking out hundreds of millions of dollars on the city’s athletes

- With government backing rising, is sporting glory for Hong Kong worth the money spent on it?

When the head of Hong Kong’s Asian Games delegation, its chef de mission Kenneth Fok Kai-kong, hosted a lunch for journalists in October, he did not speak except to issue the instruction: “Let’s eat.”

Three weeks earlier, Fok had answered only two questions at a briefing at the end of the Asiad, deflecting talk of performance reviews and road maps to greater things.

Secrecy and silent stars

He would not be alone in diverting queries. At the centre of efforts to keep the curve heading upwards is the Hong Kong Sports Institute (HKSI). Supporting its athletes has cost the government at least HK$7.4 billion (US$945 million) in the past decade.

Asked last month whether rising investment came with more responsibility to achieve better results, an HKSI spokesperson initially sent the Post a verbatim chunk of promotional text about musculoskeletal evaluations.