- Mexico 1968’s Black Power salute is the most iconic podium protest but it was far from the first

- From apartheid to Cold War, politicisation of Games has been constant from IOC, countries and athletes

There is a long history of protest around the Olympic Games, experienced by residents who do not want the city to host them, the IOC and governments, as much as the athletes themselves.

Tokyo 2020 is likely to be little different, despite the International Olympic Committee’s announcement of new guidelines banning athletes from making political, religious and ethnic demonstrations.

The first response came from Global Athlete, a group looking to represent Olympians, on Twitter. It called out the IOC’s own politicisation of sport and called for athletes to stand together. “Silencing athletes should never be tolerated,” it said.

US football gold medallist Megan Rapinoe made as much clear when she responded to that news on social media. “We will not be silenced,” she wrote on Instagram along with an image of raised fists within the Olympic rings.

The raised fist is a particularly poignant image as it evokes one of the most iconic photographs in Olympics history, arguably the most defining image of the Games.

That came in Mexico City in 1968, of course, but it was far from the first. Here we take a look at that and other protests that have helped define the Games.

Mexico 1968

The medal ceremony for the men’s 200m saw Americans Tommie Smith and John Carlos joined by Australia’s Peter Norman. The two US runners each raised a black-gloved fist during the playing of The Star-Spangled Banner and held it aloft until the anthem was finished.

The pair also went shoeless (to highlight African-American poverty) and Carlos had beads to symbolise lynchings. All three on the podium wore badges promoting human rights.

Carlos and Smith did not compete in another Olympics but were welcomed in the NFL, although injury cut Carlos down.

In 1972, Norman was overlooked by the Australia team and he was still not welcome by the time of the 2000 Sydney Games. He died in 2006, with Smith and Carlos pallbearers, and received a posthumous apology from the Australian government. Norman intimated he would have made the decision again.

The IOC’s official website has the podium protest among the video highlights, although it has changed its description of the incident. “Over and above winning medals, the black American athletes made names for themselves by an act of racial protest,” it said for many years.

At the same Olympics, Czech gymnast Vera Caslavska protested the Soviet occupation of her homeland.

She won a tied gold on the floor and a silver on the beam amid controversial judging, sharing and losing to Soviet athletes in both cases.

Caslavska turned her head away when the Soviet anthem was played.

Munich 1972

An oft-forgotten protest came four years later at the Munich Games from two more US runners: Vincent Matthews and Wayne Collett. Matthews won gold in the 400m and was joined by a barefooted Collett, who came second, on the top of the podium.

The pair raised their fists, stroked their chins and twirled their medals during the anthem after the 400m, actions pilloried by the press. They were also banned for life by the IOC and the US team were unable to defend their 4x400m relay gold from Mexico City.

Athens 1906

Going much further back in the history of the modern Olympics was Peter O’Connor. The Irishman, who competed for Britain in Athens, was the first to protest from the podium. He climbed a flagpole and then raised a flag with the legend “Erin Go Bragh” (Ireland Forever).

He got the flag out again after his gold in the hop, step and jump two days later but did not clamber up the flagpole that time.

London 1908

Two years later, the British occupation of Ireland was highlighted by athletes taking the decision to not risk a podium protest by not going to the Games.

Only a handful of Irish athletes competed, with the majority refusing to attend.

Berlin 1936

The Nazi-hosted Games led to calls for boycott, but no countries declined the invitation to compete in Germany. Pleas for the athletes to protest on the podium were sent but never reached their targets as the Gestapo intercepted them. Jesse Owens, who won gold in the 100m, was one of the athletes not to get a letter.

That’s not to say there were no protests. Before Hitler and the Nazi regime saw the OIympics as a propaganda opportunity for their race politics, many were opposed to the internationalism of the Games. A group of students styling themselves as the Fight Against the Olympic Games dug up the track at the Olympic Stadium.

Tokyo 1964

The 2020 host was also the host of the 1964 Summer Games, the first where the IOC refused to allow South Africa to take part because of its apartheid policy.

All sport in South Africa was racially segregated and as such their de facto Olympic team was all-white. An ultimatum from the IOC demanded South Africa renounce racial discrimination, but, while South Africa did pick seven non-white athletes among 62 to go to Tokyo, they were banned, while the South Africans complained that the IOC was bringing politics into sport.

This ban remained in place until the Barcelona Olympics in 1992.

Moscow 1980

The US-led boycott of the Soviet-hosted Games saw more than 60 countries refuse to go behind the Iron Curtain.

The Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan was the official reason for the boycott.

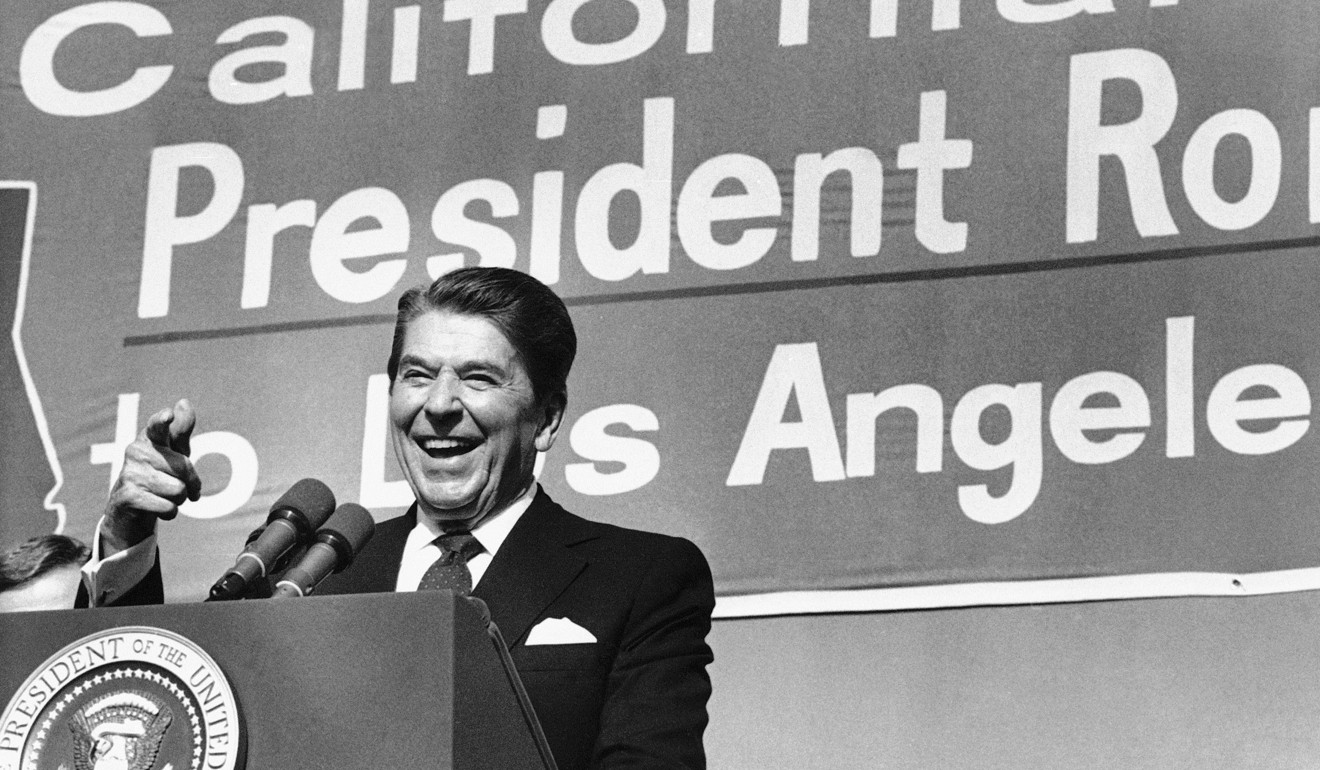

Los Angeles 1984

To the surprise of no one, the Cold War boycotts continued four years later when the Games went west.

The Soviet Union called for an Eastern Bloc boycott and only Romania attended. In addition, both Iran and Albania refused to attend, just as they had in 1980, to stand out as the only two countries to miss both Cold War-protested Games.

Sydney 2000

Cathy Freeman, the dominant 400 metres runner of the time, lit the cauldron at the opening ceremony, signalling how far Australia had come since her gold at the 1994 Commonwealth Games when the runner was treated a pariah for the “crime” of carrying the Australia and Aboriginal flags on her victory lap.

The face of the Sydney Games lived up to her billing and won the 400m. She celebrated shrouded in both the Australian and Aboriginal flags, but this time there was no reaction from Australia or the IOC – neither of which recognises the flag.

Beijing 2008

Where to start with what was always going to be one of the most controversial hosts of the Games There were protests along the Olympic torch relay route as human rights and Tibetan independence campaigners disrupted the journey to Beijing.

There were also a number of protests in Beijing ahead of the Games relating to issues such as the displacement of migrants and forcible removal of people from their homes.

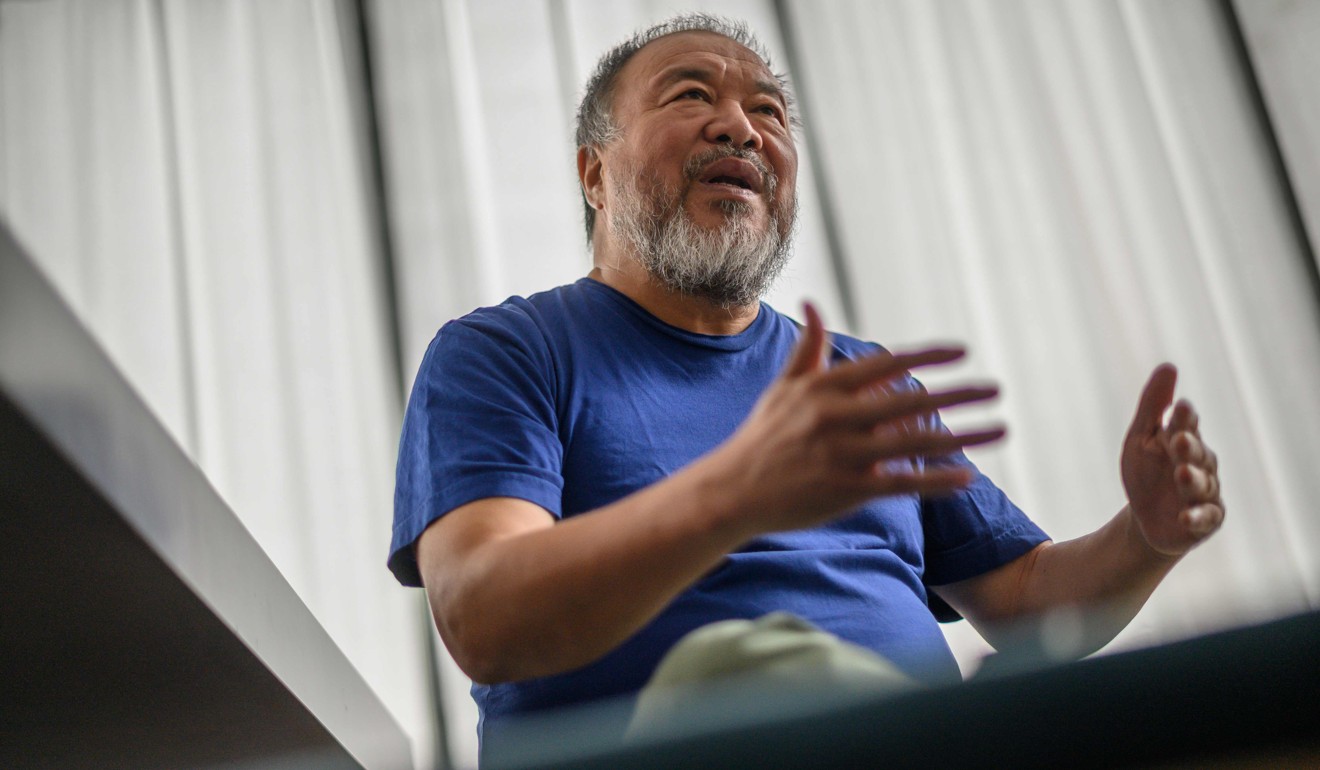

Artist Ai Weiwei, who helped design the National Stadium, better known as the Bird’s Nest, refused to attend the opening ceremony in protest at authoritarianism

As for the Games themselves, Iran’s Mohammad Alirezaei pulled out of a 100m breaststroke race that would have seen him share the pool with Israel’s Tom Be’eri, while Sweden’s Ara Abrahamian snubbed his bronze in wrestling to protest the judging.

Before all of that, FC Schalke 04, SV Werder Bremen and FC Barcelona took the IOC to the Court of Arbitration for Sport in the hopes of keeping hold of star players called up to the Olympic football squads.

Fifa eventually appealed to the clubs to cooperate and the likes of Lionel Messi played.

Rio 2016

The Brazilian Olympics was arguably the most-protested by citizens of the host country – despite the poverty gap, these Games came two years after the Fifa World Cup – and protesters were dealt with in no uncertain terms by the state security forces.

However, it was a foreign athlete who grabbed the headlines. Ethiopian marathon silver medallist Feyisa Lilela crossed the line with his wrists crossed as if shackled to highlight the incarceration of Oromo demonstrators. The Oromo are the country’s largest ethnic group but were marginalised under the then-government.

Lilela lived in exile for two years but returned to Ethiopia under a new leadership last year. He posed with Prime Minister Ahmed Abiy and President Sahle-Work Zewde for a photograph showing his hands unshackled.