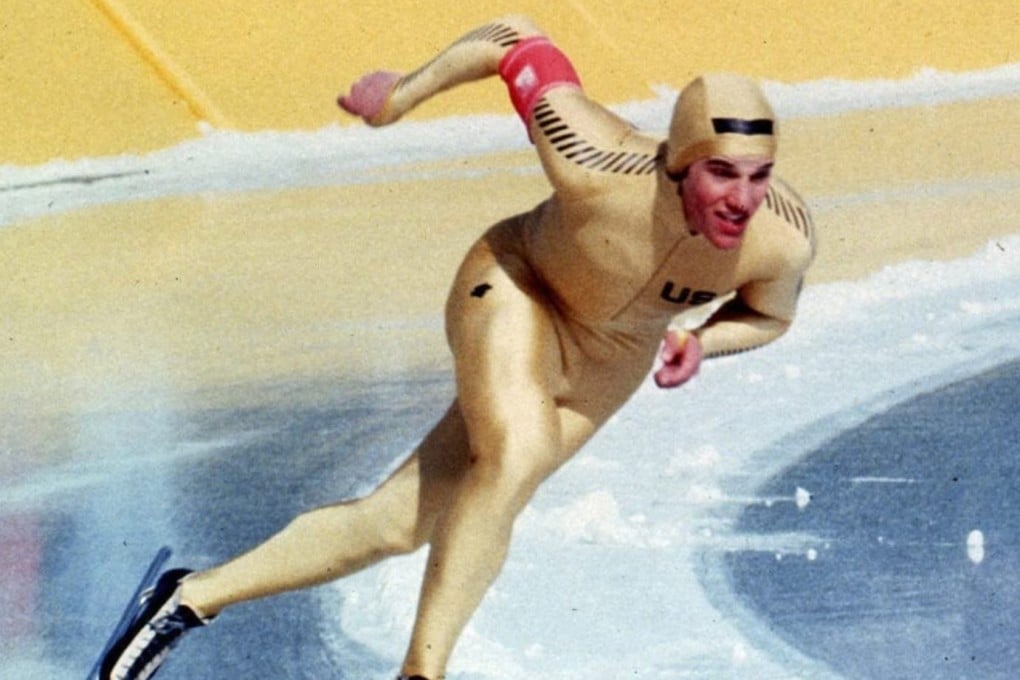

Profile | Winter Olympics: Eric Heiden, the greatest of all time, ‘imagine Usain Bolt winning the 200m, middle distances and 10,000m in a single Games’

- At the 1980 Winter Olympics, the 21-year-old American speed skater made a historic clean sweep of five track gold medals in a performance yet to be matched

- He went on to pursue a successful career as a cyclist before entering Stanford University and qualifying as a medical doctor

Post-punk and potentially pre-apocalyptic, that was pretty much the state of play in 1980 as Eric Heiden travelled to Lake Placid to make Winter Olympics history. The Cold War had reached freezing point and the world was skating on thin ice over a potential world war.

For young American skater Heiden, his battle was of different kind.

The tall, well-educated and humble speed skater was heading into his second Olympics. First time around he had been a comparative outsider in a sport dominated by northern European nations. But by 1980, he truly made his mark in the sport even before the Olympics, having won several world titles.

What he was about to achieve during those following 14 days was pure sporting history. That feat had never been accomplished before – or since. Heiden won gold in every one of the five skating events he entered, which firmly labelled him as one of the greatest athletes of all time.

To put this into perspective, imagine Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt winning the 200m, the middle distance races and the 10,000m on the running track in a singles Games.

Did Heiden honestly believe this was possible at the time? “Leading up to those Olympics in 1980 I had already proven I had the abilities to will all of those races,” Heiden told the Post. “I’d won the world sprint championships three or four times, I’d won the all-round championships, I think three times.”

He knew it was a huge ask but he also knew his intense training regimes were feared by his teammates. “Physically, I think if you looked at my make-up I was probably a good power sprint athlete,” he said. “The easiest races for me were the 1,000 and 1,500 metres, which were basically one to two-minute races.