Analysis | Tokyo 2020 Games will have record number of women taking part but are they really the first ‘gender equal’ Olympics?

- Organisers claim almost 49 per cent of those competing at the games this year are female

- Saudi Arabia only allowed its first female athlete to compete at Olympics in 2012

Our Tokyo Trail series looks at key issues surrounding the 2020 Olympics, which are scheduled for late July.

“The important thing is not to win, but to take part,” said the founder of the modern Olympics Baron Pierre de Coubertin.

This year – 125 years after the first modern Games in Athens in 1896 – we will come somewhere close to a level field it terms of participation.

“Almost 49 per cent of the athletes participating will be women, according to the IOC quota allocation,” they said, adding that there will be a record number of women competing in the Paralympics, too.

Covid-19 restrictions a headache as dope Tokyo 2020 testers remain on high alert to catch drug cheats

The question should be, is that enough?

“Numbers are just one small item: where are their voices?” asked Dr Jorge Knijnik, associate professor in the School of Education, a researcher at the Institute for Culture & Society at Western Sydney University, and author of The World Cup Chronicles: 31 days that Rocked Brazil.

“Where are the mechanisms that guarantee that women and gender diverse people have the support and the ability to break into the sporting glass gender ceiling? Gender refers to broader social issues than this superficial discussion on men X women.”

Knijnik was clear that these Games should be cancelled, with the risk of them becoming a superspreader event too big a cost, with women and gender diverse members of society the most at risk.

As Japan’s Olympics tourism boom turns bust, once-hopeful businesses count the cost

Those behind the Games are still dreaming big.

That would be some legacy and even if it were not to be realised it is fair to say that the Olympics have come a long way in a century and a quarter, not least with regard to women.

When the modern Olympics was first convened under De Coubertin, women were not welcome, just as at the ancient Games.

The Frenchman’s view was clear: “an Olympiad with females would be impractical, uninteresting, unaesthetic and improper.”

Fours year later, the patriarch of the modern Olympics was making concessions and the first women were allowed in, but in limited numbers.

Since Hélène de Pourtalès of Switzerland in 1900 became the first woman to compete in an Olympics as part of a 22-strong female contingent, the breakthroughs have kept coming.

Montreal in 1976 saw women make up more than 20 per cent of athletes for the first time, while London 2012 was the first time that every delegation had at least one woman.

Saudi Arabia was one of the countries that only allowed a female athlete to compete for the first time at that Games. This came after calls from IOC members such as Anita DeFrantz, chair of the International Olympic Committee’s Women and Sports Commission, for the country to be banned until women were allowed to compete.

“It has been more of a marathon than a sprint, but female Olympians are at last catching their male counterparts in the numbers game,” the IOC said in March 2020, after confirming that all 206 teams at the Tokyo Games – as planned before the pandemic postponement – would have full gender representation.

This year, all participating countries have to send at least one male and one female athlete. Similarly, a new rule allows one male and one female athlete to carry the flag at the opening ceremony. They are also encouraged to do so.

“When it comes to equity and inclusion in sports, the world has come a long way, but we still have a long way to go,” the US-based Women’s Sports Foundation told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in March 2020.

“The IOC’s announcement is warranted and encouraging; it signals great progress toward the ultimate goal of full equality in the Olympic Games, which continues to be a long journey.”

Even the IOC website notes the struggle: “Great progress has been made in terms of balancing the total number of athletes participating at the Games, however, many other challenges and gaps remain.”

The last 16 months have certainly been a long journey when it comes to gender equality as we saw with the scandal around the Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games (TOCOG) president Yoshiro Mori in February.

Mori, a former Japanese prime minister, said that “women talk too much” and meetings with women take too long. The scandal proved too much – eventually.

Public opinion had turned on Mori and with that threatening to make the Olympics look bad, he had to go. It appeared that the initial decision was to allow Mori to continue after he apologised, with the “issue closed” as far as the IOC were concerned.

While he had apologised amid calls for him to resign, he had said he would not stand down. More than 1,000 Games volunteers quit in protest in the two weeks after the comments.

The IOC later said that Mori’s comments were “absolutely inappropriate” and that they were “in contradiction” to the “commitments and the reforms of its Olympic Agenda 2020”.

That an 83-year-old was leading the Games says something of how distant sports administration can be from its athletes and target audience.

In the aftermath of Mori’s remarks, Tokyo 2020 chief Toshiri Muto did note that TOCOG had too few women employed in leadership roles and not one at the level of vice-president. He also downplayed the importance of gender, saying: “We simply need to choose the right person.”

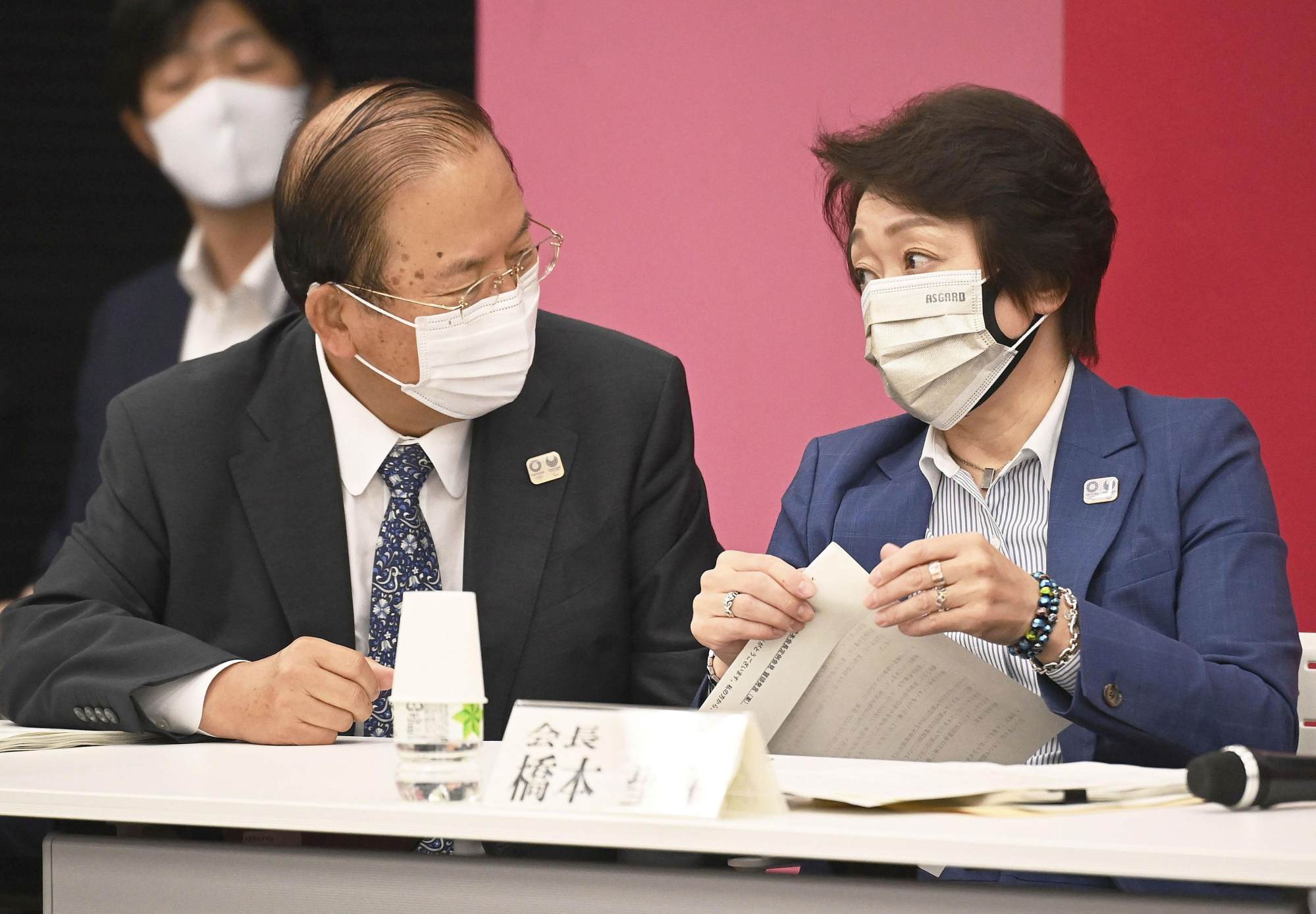

The right person was a woman, of course. Mori was replaced as president of the organising committee by Seiko Hashimoto. She swiftly announced a new committee on gender equality and described the circumstances to the Olympic Channel as “an opportunity to change the mindset of the entire nation”.

After Hashimoto’s appointment, there was a new look to the executive board with 12 more women appointed.

There are now 19 women among the 45 members. That 45 per cent female make-up does not tell the whole story, though. The committee had to be expanded from 35 to 45 members, while several spaces were made because of resignations.

Could the restructure only coming after the high-profile resignation be seen as indicative of a battle for gender equality off the pitch?

“Very indicative,” said Maureen Smith, a professor at Sacramento State and co-author of the “History of gender and gender equality in the Olympics and Paralympics” chapter of the Routledge Handbook of Sport, Gender and Sexuality.

“Leadership teams do not include anywhere close to an equal number of women within their memberships. The IOC does not require 50/50 female/male participation in leadership. I believe the IOC could be much more proactive in promoting and supporting women in leadership roles in sport, and as a result, could influence other sport organisations to follow their lead.”

This is not an issue of there being a shortage of women, it’s an issue of their being a lack of opportunities for women.

This is not an issue of there being a shortage of women, it’s an issue of their being a lack of opportunities for women

Knijnik agreed that an increase in gender diversity in senior roles is important but noted that increase does not ensure equity.

“What if these appointed women keep doing the old same stuff to block women’s and gender diverse people’s full acceptance within the sports realm? Do they have a feminist approach to sports? Will they be able to change IOC’s culture, to challenge the key tenets of the Olympic movement? Will these women be brave enough to realise that in the current conditions, the Olympics are a totally unsustainable event that cannot occur any more? That competitions need to go local?”

Perhaps greater equality within Tokyo 2020’s leadership structure only happening as an afterthought proves that gender equality is still a relatively new concern.

The Rio 2016 Games were the first where gender equality was mentioned among the legacy goals, with a focus on encouraging participation.

The IOC’s gender equality review was only launched in March 2017, looking for a “tangible outcome” before the Tokyo Olympics in 2020. The only goal at the outset? To reach 50 per cent female participation at the 2020 Games.

Yet gender equality has been enshrined in the Olympic Charter since 1996, where Rule 2, paragraph five states: “The IOC strongly encourages, by appropriate means, the promotion of women in sport at all levels and in all structures … with a view to the strict application of the principle of equality of men and women.”

While it might have long been on the books, gender equality is definitely now on the agenda. Quite literally. Earlier this year it was made one of the primary focuses of “Olympic Agenda 2020+5”, their new strategic road map.

The IOC said it is “leading by example in gender equality”. It points to increases in female IOC membership (37.5 per cent from 21 per cent), female representation on the IOC executive board (33.3 per cent from 26.6 per cent) and female members on the IOC’s commissions (47.8 per cent from 20.3 per cent).

Smith wants to see an even split of men and women in IOC leadership – “I would set 50 per cent as the benchmark and meet it,” she said.

“There are so many well-qualified women across sports and around the globe. This is not an issue of there being a shortage of women, it’s an issue of their being a lack of opportunities for women,” Smith said.

The IOC says that the next focus is on coaches – another area Smith highlighted – of which around only 10 per cent are women, while Paris 2024 will have genuine gender equality in its 50-50 split of athletes.

Perhaps Hashimoto had it right when she said, “We resolve to make the Tokyo 2020 Games considered as a turning point in history when looking back many years later.”

We might, but not how Hashimoto hopes. Smith argues that the coronavirus pandemic may have the final word.

“It’s hard to gauge these Games,” she said. “Some countries may not send teams, altering numbers. Some athletes will choose not to attend based on IOC/Tokyo restrictions on families being able to attend.

“If anything, these Games are falling short on Covid.”

Maybe De Coubertin was right that it is all about taking part.