Women are no longer a novelty in China’s e-sports scene but challenges remain for pro gamers

Competitive electronic sports, or e-sports in short, have grown rapidly in popularity as digitally savvy millennials and Generation Z spend more time playing online games

It is a balmy March evening in Hainan, the sun-soaked island province that has earned a reputation for being China’s answer to Florida or Hawaii for wintering snowbirds escaping the frigid north.

At the cavernous convention centre in the provincial capital, where a weeklong electronic sports tournament is being held, a steady stream of people are leaving the venue in search for dinner.

But food will have to wait for Fang Dongmei and her fellow teammates of LLG, an all-women e-sports team competing at the World Electronic Sports Games (WESG), a multi-event competition structured much like the Olympics with preliminary heats and finals.

They remained seated in front of their Dell monitors in the training area, tapping intently at their keyboards. The team captain, Yang Ting, a 32-year-old from Hunan province, barked orders into her headset, directing her team of five to advance on the enemy in Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (CS: GO).

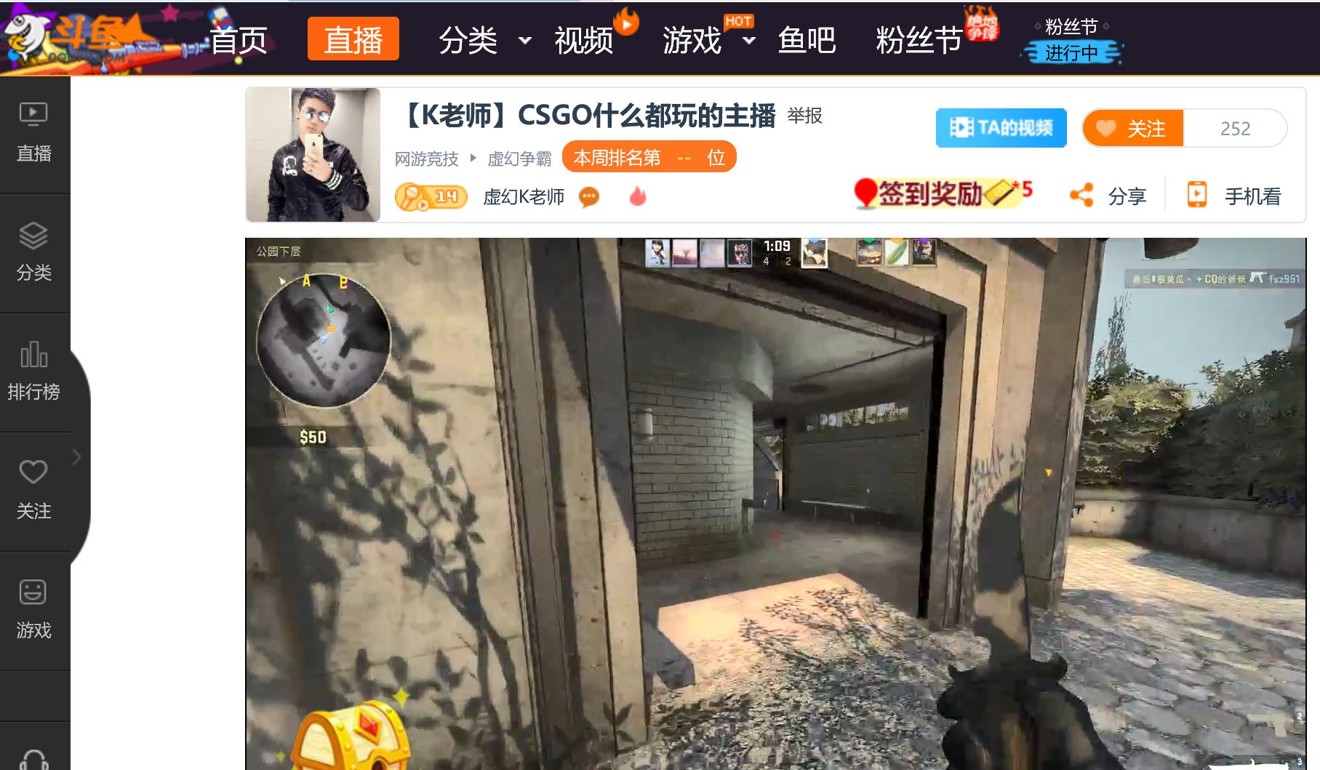

For the uninitiated, CS: GO is what is called a first-person shooter video game that is somewhat like virtual paintball. When contact is made, Fang’s screen lights up in a hail of bullets and exploding grenades. Hand-to-hand combat ensued, Rambo-like serrated blades drawn, every avatar for itself.

LLG is doing some last-minute prep for the next day, when they play teams from Brazil, Russia and Singapore. There are eight teams competing in the women’s category of CS: GO and the winner takes home US$100,000.

Competitive electronic sports, or e-sports in short, have grown rapidly in popularity as digitally savvy millennials and so-called Generation Z spend more time playing online games.

In China, that has been a lucrative business for leading games publishers such as Tencent, NetEase and Perfect World. Now the world’s biggest gaming market, the industry raked in an estimated US$27.5 billion in revenue last year, according to Newzoo.

The growth of gaming has boosted investments in related businesses, creating an eco-system that includes tournament organisers, online video companies that live-cast and replay competitions, purpose-built e-sports stadiums, smartphone makers and digital games developers.

“I've been playing Counter-Strike since I was 12, for 6 or 7 hours each day,” said Fang, who goes by the moniker “Leo” when playing CS: GO. “Becoming a full-time e-sports player has always been my dream.”

Like with other professional sports, the rewards are heavily skewed to the best teams and players, with top-earners pulling in seven-figure sums in prize money and sponsorship. For those striving to break into the elite ranks, catching that big break can take years of training and competing in smaller tournaments while trying to make ends meet, without a guarantee of success.

In China, the focus at this stage of development is on building successful and profitable tournament franchises, infrastructure and game titles, according to interviews with players, tournament organisers and analysts. Against that backdrop, player welfare and creating sustainable career paths for pro players rank lower down on the priority list.

Fang, who is 22, moved to Shanghai in November to join LLG, where she drew a monthly stipend of 5,000 yuan (US$793), or half the average salary of that city. Even though that is more than double what she earned working in the finance department of a company in Guangzhou, the living costs are also higher in Shanghai, one of China’s richest and most cosmopolitan cities.

That compares with top male players, who can make upwards of 10,000 yuan (US$1,591) in monthly salary in a professional team, according to interviews with several pro gamers. But the real money is in tournaments. Open-category competitions, which are open to both men and women, have much bigger payouts than women-only events.

At the WESG, the total prize money for the women’s category in online collectible card game Hearthstone was US$51,000, compared with US$150,000 for the open category.

The disparity arises from gaming being historically a male-dominated sphere, but things will improve as the sport matures, according to Macquarie analyst Zhang Jiang.

“Better female representation will come and will be necessary for the professionalisation as well as the legitimacy of the industry”, said Zhang, who is based in Toronto and follows the technology and gaming industries. “However, this will not happen overnight and changes will be gradual.”

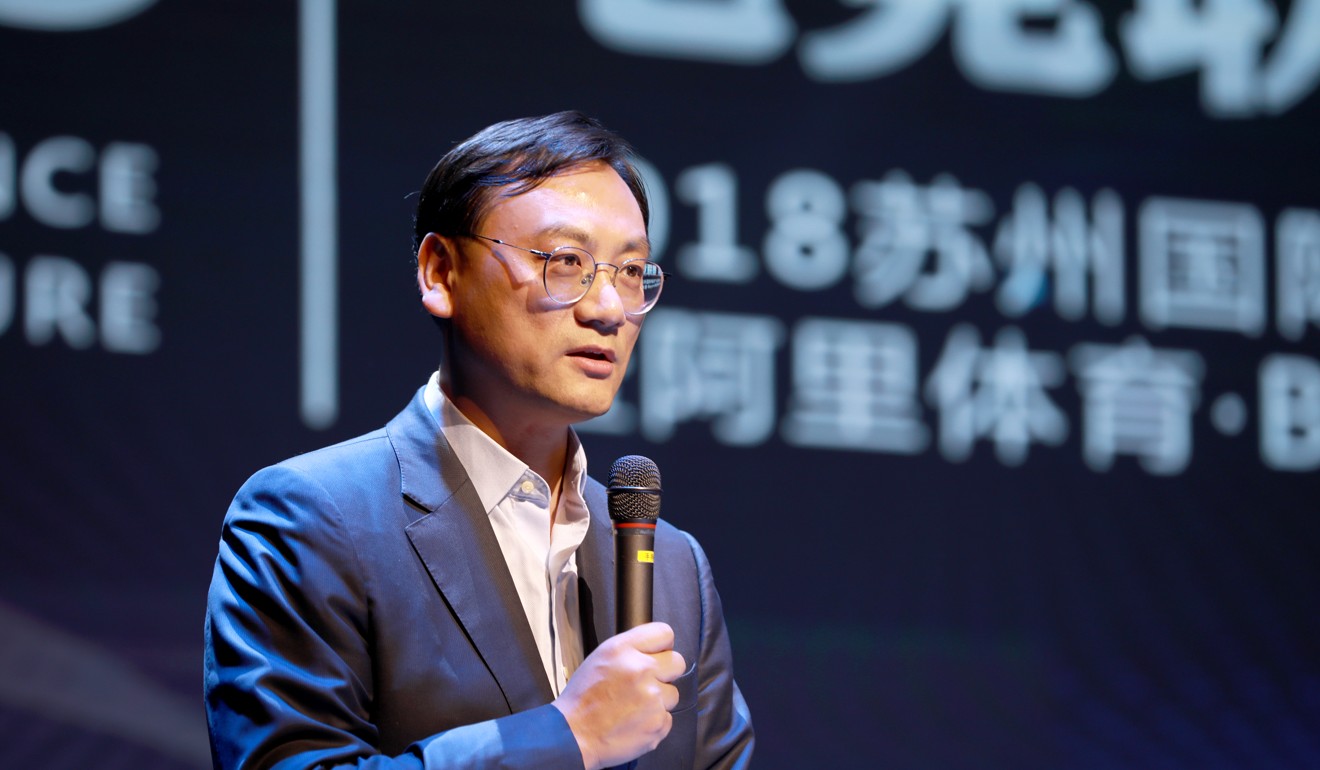

To promote female participation at the top levels of e-sports, Alisports is hosting competitions like WESG and creating women-only categories to ensure they get more exposure, according to chief executive Zhang Dazhong. Other competitions that have women-only categories include the Intel Extreme Masters in Katowice, Poland and the annual Copenhagen Games in Denmark.

E-sports will be a medal event at the 2022 Asian Games, which will be held in the city of Hangzhou, where Alisports’ parent Alibaba Group is based. Alibaba owns the South China Morning Post.

Besides professional gamers, the popularity of e-sports has given rise to new careers such as gaming referees and commentators.

Wang Xuewen, 22, is one of the few female officials at the WESG. Rushing around the halls to referee matches for DOTA 2, a multiplayer battle arena game, the final-year undergraduate from Henan province is hoping to make a career out of officiating e-sports.

“I love DOTA 2 and have been playing it for a few years, but I don’t have plans on becoming an e-sports player as I’m not playing at that high of a standard,” said Wang, who is paid a daily rate for her refereeing, which she declined to disclose.

“When I graduate, I hope to pursue a career in the e-sports industry and help legitimise this as a sport, even if my parents may not be happy with my decision”, she said.

Some competitors, though, are paying their own way and taking part for the love of the sport.

Chen Yuxi, 23, who goes by the username “GLHuiHui” when she is playing Hearthstone, has been honing her skills at the online collectible card game since she entered university five years ago. She borrowed money from her mother to participate in a tournament in Guangzhou last year.

“I felt like my social circle was too small and wanted to join competitions to meet friends and like-minded people,” said Chen, who won two Hearthstone tournaments organised by game developer Blizzard in China last year, where she competed against men.

At the WESG, the Suzhou resident won US$30,000 and has set herself a goal of competing at the world’s biggest Hearthshone tournament some day.

For Fang, the LLG player, the late dinners and extra training that week in Haikou paid off with a runner-up placing in the women’s category. After deducting costs, Fang’s share of the spoils came to about US$3,200. The team disbanded after the tournament.

She plans to leave Shanghai and return to Guangzhou, where she will start playing games on live-streaming platforms while she contemplates her next move. Viewers can reward skilful players with digital “gifts” that can be redeemed for money.

“My parents worry about the stability of my career as an e-sports player,” Fang said. “If e-sports does not work out, I want to learn how to code and switch careers. I'm not keen on going back to accounting.”