How Chinese tech start-ups are cashing in on country bumpkins

Almost half of China’s 1.3 billion people remain unconnected to the internet, providing tech companies with a potential new market as spending by richer, tech-savvy urban residents levels off

Dai Wei, a 55-year-old retired worker whose main responsibility is taking care of her grandson, has suddenly been thrust into the spotlight of China’s latest internet trend.

With no job, no spending money to speak of and only one year’s experience using a smartphone, Dai, who lives in a small county in northern China’s Hebei province, is being courted by some of China’s hottest internet start-ups, even one-upping her tech-savvy daughter in Beijing by becoming an early adopter of two trendy new apps.

Chinese news app Qutoutiao has been giving Dai small cash rebates to encourage her to browse its lowbrow comedy videos and social news content, while social e-commerce app Pinduoduo is offering heavily discounted and even free goods if she finds more than five friends or family members to take part in the Groupon-style online purchases.

The marketing promotions signal a new wave in China’s rapidly evolving internet landscape, in which the so-called diaosi – the Chinese equivalent of country bumpkins – are now sought after as spending by higher income, tech-savvy urban residents has levelled off after years of rapid growth.

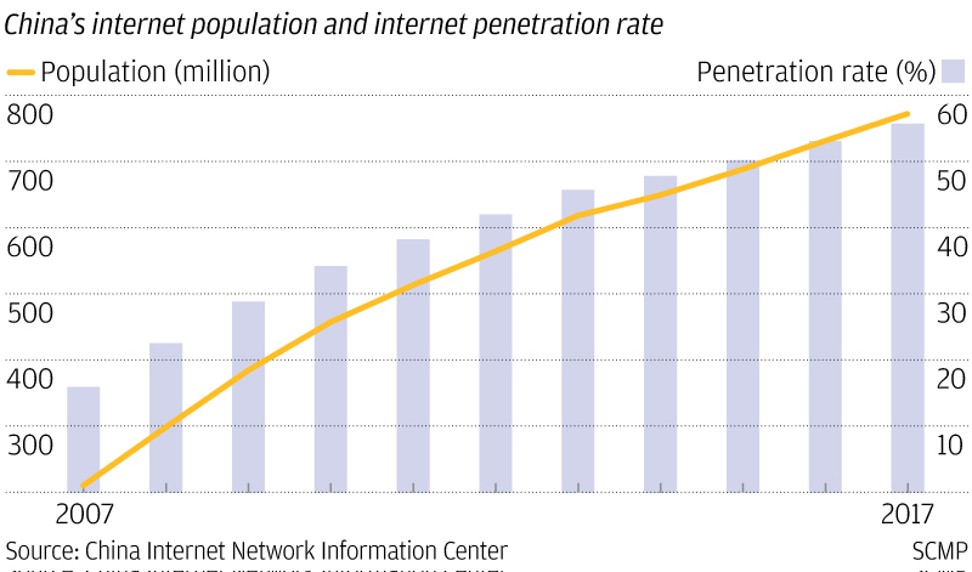

With 772 million online users at the end of 2017, China’s internet population is bigger than that of India and the US combined.

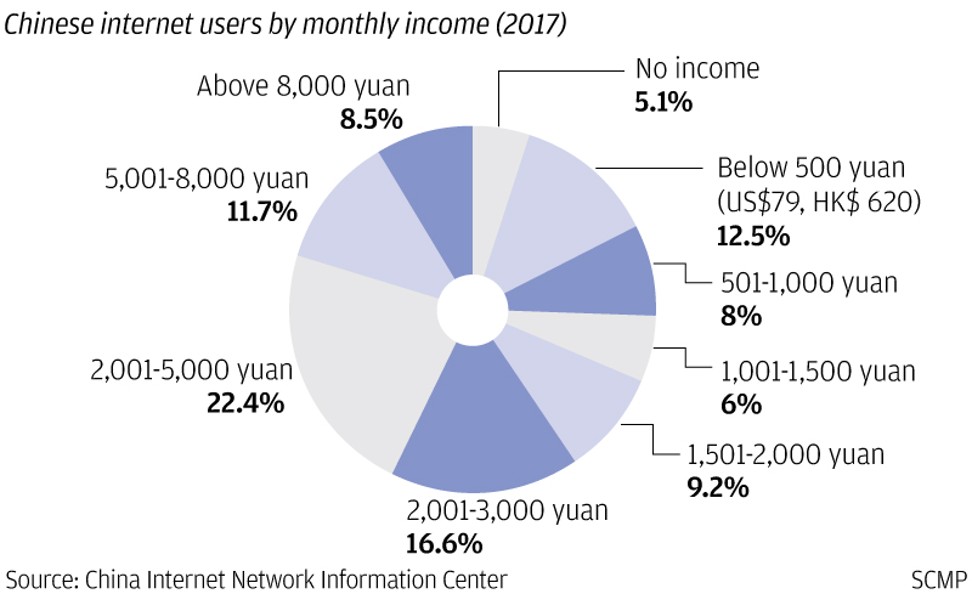

While many of these are young, well-educated urbanites accustomed to swiping their smartphones to pay for dinner or shopping online to buy imported cherries from Chile, almost half the Chinese population remains unconnected to the internet, meaning diaosi are a new target group potentially worth billions of dollars for any successful internet business.

“The rest of the world, including wealthier parts of China, have been talking about a consumption upgrade, but for the [lower tier cities] which have massive market potential, cheapness is always attractive and is largely what appeals to those consumers,” said Jay Liu, senior manager at CKGSB Chuang Community, an accelerator for Chinese start-ups, including Pinduoduo.

While it may be common for middle-class families in Shanghai to enjoy overseas holidays at least once a year and office workers in Beijing to spend more than 10,000 yuan (U$1,583) on a Gucci handbag, data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics shows that the country’s per capita disposable income was 25,974 yuan last year, dropping to 13,432 yuan in rural areas.

China’s internet majors, including its top two e-commerce players Alibaba Group Holding and JD.com, have launched a string of initiatives to try to get into smaller cities, from on the ground market education to drone-enabled delivery services in mountainous areas. Start-ups such as Pinduoduo and Qutoutiao have built a marketing strategy from the very start to specifically target lower tier cities. Alibaba is the parent company of the South China Morning Post.

By directly connecting China’s domestic manufacturers to shoppers, Shanghai Xunmeng Information Technology has developed its Pinduoduo e-commerce platform into one of the fastest growing companies in China, reaching 156 million monthly active users within its first two-and-a-half years, according to QuestMobile. In comparison, monthly active users for JD.com and Alibaba were 226 million and 515 million respectively at the end of 2017 after nearly 20 years of development.

“Most fourth-tier and village consumers have never driven a car. They have never owned a passport. They get their entertainment from smartphones, not from going to the movies or taking trips,” said Jeffrey Towson, a Peking University professor who specialises in Chinese consumers and the digital economy.

“[They] are more frugal and value focused and are not as brand conscious or loyal, and for them word of mouth is still the most important form of advertising,” said Towson, who is the author of The One Hour China Consumer Book.

On the Pinduoduo app, Dai has snapped up bargains by joining together with friends and family, including a bedsheet priced at 19.9 yuan and a 39 yuan down jacket, both of which were delivered free to her doorstep.

Qutoutiao, which translates as “interesting headlines,” said about 80 per cent of its more than 10 million daily active users live in third-tier cities, about 70 per cent of its readers are women, and 35 per cent of those are aged over 40.

The Shanghai-based company, founded in June 2016, said it sees promising business potential for the underserved demand for such news in tier three cities. The strategy has already paid off, with the start-up recently reaching unicorn status after a US$200 million funding round led by Chinese internet giant Tencent Holdings in March.

Besides using sensational news to keep viewers around, Qutoutiao runs a reward programme – paying about one-tenth of a yuan per user per day – to encourage readers stay on the app.

Dai has accumulated more than 10 yuan of reward money in her Qutoutiao account – half the cost of another bedsheet from Pinduoduo – though she says the money is not the only reason she keeps using the app.

Qutoutiao declined to make an executive available for an interview on its marketing strategy but provided an emailed response: “China’s internet market is highly competitive. In ride-hailing, food delivery and e-commerce, many companies offer customer subsidies to succeed in business. We are no different. Compared with spending a lot of money on advertising, why not just give the money to our users?”

Despite the success of Pinduoduo and Qutoutiao they have come under fire, with Chinese media accusing them of taking advantage of people with lower incomes and education levels. Some media commentators have labelled the companies as examples of “consumption degrade”, accusing Pinduoduo of providing poor-quality goods and Qutoutiao of feeding people content in poor taste.

Pinduoduo received about 15 per cent of all complaints among the 10 major Chinese e-commerce sites monitored in 2017, second after Alibaba’s Tmall and Taobao platforms, according to Hangzhou-based internet consultancy China E-Commerce Research Centre. Most of the complaints were related to product quality.

Pinduoduo has not responded to numerous queries sent by the Post over the past two weeks about the quality issue. But its chief executive Huang Zheng denied that the company’s core competence was “cheapness” in an interview with Chinese business news magazine Caijing in early April. “Only traditional companies divide people by using the standard of tier one or tier two. We want to satisfy the different demands of every person. One can shop for a Hermes handbag but still buy a 9.9 yuan box of mangoes from our site,” he was quoted as saying in the Caijing report.

The statement from Qutoutiao pushed back on any perception that its content was lowbrow. “Media or people in tier-one and tier-two cities are using the word ‘lowbrow’ to describe us and in reading behaviours of those in smaller cities. We are strongly against vulgar content. It is just that there is different demand for content between those in small towns and mega cities,” the statement said.

So far there are no indications the censorship crackdown has affected Qutoutiao, even though it has a similar content strategy as Toutiou.

Li Sujie, the 30-year-old daughter of Hebei grandmother Dai, said she used to think the Pinduoduo shopping links her mother posted via WeChat were tactics to trick the elderly into making purchases.

“The design of the user interface on Pinduoduo looks quite low-end and the products on sale look so cheap, but after I tried it I think it is an ideal place to buy necessities, such as dishclothes and garbage bags,” Li said. “As long as they can provide good-quality basic products, I can shop there from time to time.”