TikTok becomes a case study for Chinese companies planning global expansion

- ByteDance’s purchase of video app Musical.ly would give Zhang a platform to venture into global markets – and sow the seeds of future troubles

- One lesson ByteDance has learned from its globalisation experience is the need for professional communication skills

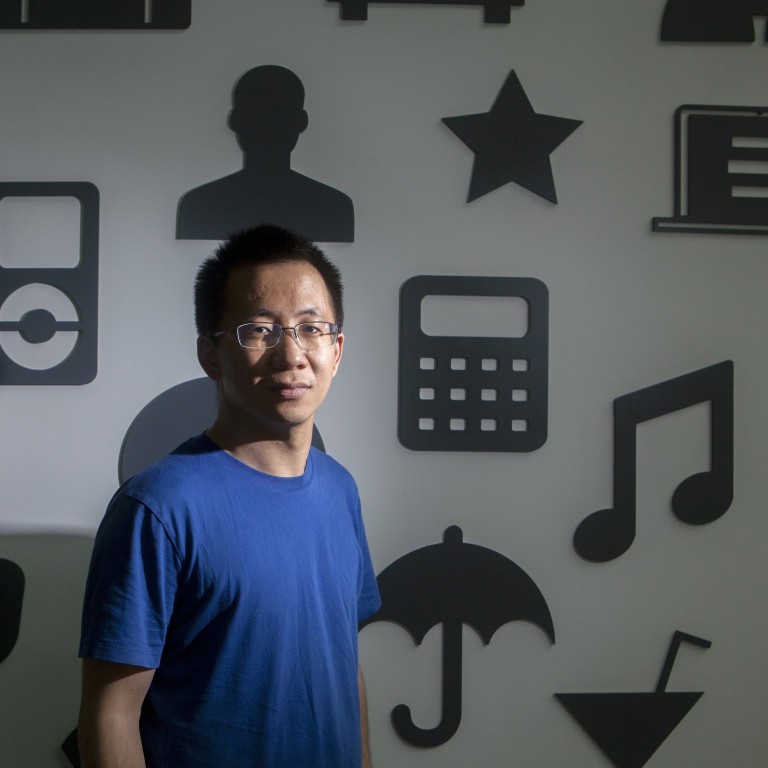

Zhang Yiming’s new year’s resolution in January 2017 was to “learn English well,” according to a private WeChat Moments post seen by the Post. He was sharing what he called his “dream” among close friends and aides – and made the point by adding in English: “I mean it!”

Eleven months later, Zhang’s company ByteDance purchased video app Musical.ly in a deal that would give him a platform to venture into global markets. It would also sow the seeds of future troubles, but serve as an important lesson for other Chinese companies looking to enter Western markets.

TikTok has found itself in a complex geopolitical situation during “the lowest point” of Sino-US relations since the two countries established diplomatic ties in 1979, according to Wang Yong, a professor at the Peking University School of International Studies. The US now “views China as its main competitor [and] targets Chinese hi-tech companies in particular”, he said.

Following a review of its Musical.ly acquisition by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), Washington ordered the divestment of TikTok’s US operations from its Chinese owner ByteDance, citing national security concerns. But updated export controls issued by Beijing in late August – which covered two key technologies used by the short video app – added more uncertainty to the sale.

On Monday, Oracle emerged as the front runner in the contest to reach a deal with TikTok after Microsoft Corp said its offer for the video app had been rejected by ByteDance. The decision to pursue a partnership with Oracle rather than an outright sale has also kicked the ball back into Trump’s court. The US president had ordered TikTok to close its US operations if an American buyer could not be found.

Oracle’s TikTok bid ‘does not address US security concerns’

But why did TikTok become the next target after Huawei Technologies, the Chinese telecoms giant crippled by US government sanctions over similar national security concerns?

Like the founders of most Chinese tech giants, Zhang’s relationship with the ruling Communist Party is complicated. He must walk a fine line between keeping Beijing happy but not be seen as too close to raise concerns outside China.

Zhang, who told Atlantic magazine in July that he was not a party member, was approached by Beijing a year ago with an offer to help when TikTok faced political troubles in India. However, Zhang sent mid-level staff to meet government officials, signalling he did not want Beijing to get involved, Reuters reported this month, citing anonymous sources.

But when Beijing is displeased, tech companies act swiftly. In 2018, ByteDance was ordered to close its popular humour app Neihan Duanzi after it was criticised for having vulgar content. Zhang made a public apology and vowed to strengthen “party building” in the company.

Lu Wei, China’s heavy-handed internet tsar who was sentenced to 14 years in prison for corruption last year, was a fan of ByteDance’s news site Toutiao and told other internet companies that they should work with the company, according to The New York Times, citing anonymous sources.

ByteDance denied it had a close relationship with Lu or benefited from any connection with him, according to the report.

Nonetheless, amid the recent troubles in the US, ByteDance’s relationship with Beijing has become closer. Zhang’s team requested a meeting on his behalf with China’s ambassador in Washington, Cui Tiankai, according to the Reuters report.

01:46

Oracle reaches deal to become TikTok’s ‘technology partner’, after Microsoft offer is rejected

In assessing lessons learned from the experience, Zhang might look back to 2017 and view the decision to not notify CFIUS of its Musical.ly acquisition as a misstep. While notification was not mandatory in this case, had ByteDance been more proactive in ensuring the deal was not a problem in the eyes of Washington, the situation today could be very different with regard to the CFIUS order, according to analysts.

“CFIUS might have said [the deal] didn’t need a review or told them it didn’t pose a national security threat after doing a review,” Zhou Qing, a lawyer who helped China’s heavy machine maker Sany Group sue the Obama administration, told the Post in an interview.

“It’s also possible that they would have blocked the acquisition in the first place due to national security concerns, but no matter what, it would be impossible for CFIUS to do a turnaround today if ByteDance had reported the deal before,” he said.

TikTok is not the first time the US government has pushed back on foreign tech investments from China. In 2018, Washington blocked a US$1.2 billion offer by then Ant Financial to purchase MoneyGram, citing national security concerns. Ant is an affiliate of Alibaba Group, owner of the Post.

Last year, Chinese gaming company Beijing Kunlun Tech was forced to sell Grindr, the popular gay dating app it bought in 2016, after a US government national security panel raised concerns over whether the ownership gave the Chinese access to sensitive information about US citizens.

Tencent relinquishes rights to PUBG Mobile in India amid latest ban on Chinese apps

In the case of Sany, President Barack Obama issued an executive order in 2012 requiring the Chinese company’s affiliate Ralls to divest all interests and remove structures from a wind farm it purchased near a US naval facility. In the subsequent legal challenge, the court ruled that CFIUS had failed to provide Ralls with constitutional due process.

It was seen as a significant case as CFIUS had never been challenged by a Chinese enterprise since it was established in 1975. Sany reached a settlement with the US government in 2015 in which it was allowed to sell the wind farm project to a third party.

Zhou, the lawyer who represented Sany, said the US president has “full discretion” to declare whether a company poses a national security threat – putting companies like TikTok and Huawei in difficult situations. “It’s impossible to argue with the US government whether the company poses [such a] threat,” he said.

“The court won’t make a judgment on that, or say that the president’s decision was a mistake. The judge would only test the procedural issues with respect to a lawsuit referring to CFIUS,” he added.

The political environment has changed a great deal since the Sany case. After a trip to Silicon Valley in 2014, ByteDance’s Zhang penned an article titled “The golden times of Chinese tech companies”. His optimism was widely shared. In 2016, when Zhang was interviewed on state owned CCTV, he was joined by Colin Huang, founder of e-commerce site Pinduoduo, who encouraged his peer to be “more active” in globalisation.

One lesson ByteDance has learned from its globalisation experience is the need for professional communication skills. In the three months ended June 30, the company spent US$500,000 on US lobbyists, up from its previous record of US$300,000 in the first quarter, according to figures provided by ByteDance under the Lobbying Disclosure Act.

In comparison, Huawei spent US$1.7 million in just three months, from July to September 2019, after it was added to the US entity list banning from purchasing US products, although that has fallen to US$170,000 in the most recent quarter, according to Huawei’s lobbying disclosure.

Wang from Peking University said Chinese tech companies will need to hire more legal and political experts to understand the business environment in overseas countries, while maintaining communication with Chinese government officials. “Facing a very different political environment and more regulation, tech companies must learn how to lower their political risk,” he said.

The geopolitical problems are not confined to the US and China. In June, TikTok was among 59 Chinese apps banned in India after a deadly border clash. The Indian government took further action this month, banning another 118 Chinese apps, including “VPN for TikTok” and Tencent Holdings’ hit mobile game PUBG Mobile.

“The international environment for Chinese enterprises has become more and more difficult,” said Wang, adding that the problems were not specific to Chinese firms as there was an “anti-globalism trend” developing.

“The peak of globalisation has already passed...I think it may take another two to five years, when the economy resumes... before the environment for Chinese enterprises to go overseas becomes better,” he said.

Dev Lewis, a fellow at Hong Kong-based think tank Digital Asia Hub, said Chinese companies could still expand globally but the markets they can tap into will be much smaller. “Southeast Asia and South Asia, those are huge opportunities, but they are not the most revenue-generating markets, so how do [companies] balance that?”

TikTok has been downloaded more than 378 million times in Southeast Asia, with Indonesia contributing more than 41 per cent of that number, according to data provider Sensor Tower. In 2020, downloads in the region increased 145 per cent year on year for the period from January 1 to September 13, the research firm told the Post.

In Southeast Asia, TikTok’s approach has been to quickly launch “non-political” products and promise governments in countries like Vietnam that its content will be tightly policed in accordance with local laws, Reuters reported in late August, citing interviews with current and former employees.

Bill Plummer knows about political pitfalls. He was Huawei’s vice-president for external affairs in Washington from 2010 to 2018, where his job was to convince lawmakers the company was not a threat to national security.

There is still a “solid opportunity for China-based companies” in the world market but that opportunity will be more limited in the “US and its allied countries when it comes to industries perceived as critical infrastructure”, said Plummer, who now works as an independent strategy consultant.

Nobody knows if the Oracle deal will be approved by Trump, but Zhang continues to maintain a low profile despite being at the centre of a global geopolitical storm. He rarely expresses his feelings publicly, but a monologue shared with colleagues four years ago sheds some light on what might be going through his mind now.

“Sometimes I‘m a bit unhappy, and I’m unhappy usually because of disappointment,” Zhang said. The world will find out soon enough how he really feels.