Web browsers hopping the Great Firewall in China suggest a new era of opening up and a new means of control

- China allows some web browsers to offer access to blocked websites like YouTube and Facebook while still censoring what users see

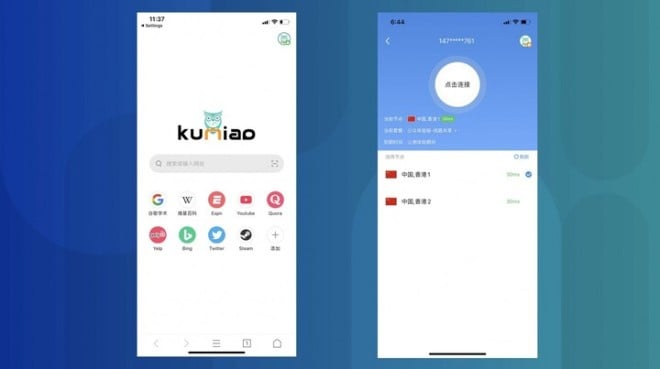

- Browsers Tuber and Kuniao were both pulled from app stores following a surge in popularity

Web browsers that let netizens in China jump the Great Firewall have become more common over the last year. Their appearance seems to offer a glimpse at what could be a new form of internet censorship in China.

Some of these browsers, which let users circumvent the government’s strict online censorship, manage to stick around for a while. But the quick withdrawal of others has led to questions about whether these browsers are really sanctioned by authorities as some companies say.

The story of China’s Great Firewall, the world’s most sophisticated censorship system

Like other similar apps, Tuber said it offered legal access to sites that are normally blocked in China like YouTube and Facebook. But the day after news of the app went viral, it was gone from Chinese app stores.

While Tuber was short-lived, this does not mean it was illegal. There are several similar browsers, sometimes called “cross-border browsers”, from companies that say they are operating legally. And for some apps, the similarities may not be an accident.

“There seems to be some remarkable code similarity among Kuniao, Tuber, Qingsou, and Linghu, suggesting that all four browsers may have a close phylogenic relationship,” said Jeffrey Knockel, a researcher at the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab, who tracks internet censorship and surveillance. Kuniao, Qingsou and Linghu are three other browsers that let users bypass the Great Firewall and are made by separate companies.

Another such browser is “Leitu cross-border browser”, which remains available for download on its website and comes from a company named Jiangsu Cuiqi in the eastern city of Nanjing. The only contact method listed on the site for Leitu was a phone number for customer support. We talked with customer support online, but later attempts to reach them by phone went unanswered.

When asked why the browser is able to work in China, customer support said it is “absolutely legal” because it cooperates with “relevant departments” and blocks illegal content.

“It’s [made] purely to satisfy ordinary demands, you can’t do anything illegal with it,” they said.

Leitu markets itself as a tool for users to “smoothly visit” Google, YouTube, Facebook and Twitter and access other foreign content like academic resources and games. Customer support said the browser is designed to satisfy the needs of companies with foreign operations, but it is also available for individual use.

Besides Qihoo 360, at least one other big tech company has also dabbled in this area. Knockel notes that Baidu Browser, from the company that operates China’s biggest search engine, had a proxy feature that permitted access to some websites that are normally blocked.

China still loves Chrome even though Google is blocked

All these browsers offer people in China access to the global web while still allowing authorities to strictly control what people see. A custom web browser is uniquely suited to this task.

The most common means of circumventing internet censorship in China is a virtual private network (VPN). This encrypts all data between a user’s computer and an overseas server that is not blocked in China, letting users view whatever they like. But a web browser can potentially snoop on everything a user sees and block disagreeable content if it is built to do so.

This is not just speculative. Some Chinese browsers have already been caught blocking content that would normally not be blocked by the Great Firewall.

Knockel also said that QQ Browser and UC Browser, another popular browser in China, transmitted the full URLs of every site users visited back to the companies, suggesting that this behaviour is common among Chinese browsers. UCWeb, the developer of UC Browser, and the South China Morning Post are both subsidiaries of Alibaba Group Holding.

Alibaba fixed all the issues flagged by researchers at the time, according to reports from The Citizen Lab in 2016. Tencent also fixed some issues, saying they had “tried their best to resolve all reported problems”, although The Citizen Lab said at the time that they could still see some sensitive user information such as hard drive serial numbers.

Leitu has not been examined for this type of behavior, but the company says on its website that it filters out content.

“Leitu’s solution obeys the cybersecurity law,” the website reads. “Visit overseas websites through the browser. It automatically filters illegal information.”

Customer support for Qingsou also said its browser blocks illegal content, singling out pornography, gambling, drugs and political content as examples of things that would be blocked. Qingsou is made by a little-known company in Shanghai called Kunao, which also makes VPN apps.

Before Tuber disappeared, multiple media outlets tried searching for material related to sensitive topics in China within the app. Terms like “Xi Jinping” and “Tiananmen” offered no results.

For Chinese citizens, these kinds of searches may not be without risk. To use these browsers, people have to register with a Chinese phone number, which is linked to the owner’s national ID number. This means people’s real identities can be tied to their usage of the apps. Tuber even warned in its terms of service that users who “actively watch or share” content deemed illegal could have their data shared with “relevant authorities”.

If these apps really are state-sanctioned, that could be a cold comfort for some users. When asked about this, Linghu’s customer support said that it is a public-private partnership project, a type of project that involves the government. The company would not answer further questions.

This disappearing act is part of the reason questions persist about government support for this kind of software. China’s censorship rules have always been opaque and inconsistent, so few people found it surprising when Tuber and Kuniao were removed from app stores. But Leitu, Qingsong and Linghu all have registered internet content provider (ICP) licenses for their websites, according to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT). An ICP license is required for a website to be legally hosted in mainland China.

Like many businesses in China, these apps are likely just trying to find a way through the legal grey areas, said Charlie Smith, co-founder at Greatfire.org, an organisation that monitors online censorship in China. Their solution, according to Smith, is enforcing real-name registration.

But if these apps get too hot, too fast, that could cause problems.

“Tuber experienced a wild weekend of downloads that spooked whoever thought that it was a good idea to allow this app into their app store in the first place,” Smith said.

If too much attention is a problem, some may wonder why the government would allow this software at all. One prevailing theory is that the Great Firewall is too blunt an instrument.

After nearly two decades of operation, the Great Firewall has become increasingly adept at adapting to new situations. But even its creator, Fang Binxing, has acknowledged that the system filters too much information, both harmful and benign.

“The firewall monitors them and blocks them all,” Fang said in a 2011 interview with the state-run tabloid Global Times. “It’s like when passengers aren’t allowed to take water aboard an airplane because our security gates aren’t good enough to differentiate between water and nitroglycerine.”

This is why some speculate that these browsers are a way for Beijing to experiment with offering easier access to foreign websites while still maintaining control.

“I think having an app like Tuber would be in the interest of the CCP,” said Molly Roberts, associate professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego, and author of the book Censored: Distraction and Diversion Inside China‘s Great Firewall. “There is lots of demand for information outside of the Great Firewall, particularly for entertainment. Having an app that allows access to that information while also censoring political information and surveilling might satiate that demand while having few political ramifications and without leading people to VPNs.”

This, however, does not mean that the Chinese government is making the internet more open. Roberts noted that apps like Tuber could more effectively hide censorship.

“What we know from academic research is that awareness of censorship is key to countering it,” she said. “So if apps are seemingly more open but are actually filtering, this could still have a big impact on access to information and perceptions of the information environment, even if YouTube, Google and Facebook are no longer completely blocked.”

However, VPNs still remain a reliable gateway to the outside world for many, even as the Chinese government has cracked down the tool in recent years. So authorities might not see any immediate need to change how the Great Firewall currently works.

“Chinese authorities have long admitted the need for VPNs, especially for the business use case,” Smith said. “If Chinese businesses want to operate effectively on an international basis, they need to be able to access overseas websites that can help them – and many of those are blocked in China. This is one reason why the Chinese authorities do not completely shut down VPNs.”

While Tuber got to see its popularity briefly soar, it is not clear how many people are using the similar but lesser-known browsers that remain available. It is possible that privacy concerns could be hurting the apps, but it is not because of potential government snooping.

Before discussions about Tuber started being censored on social media, many netizens said they suspected the app was a phishing scam aimed at closely monitoring people’s online behaviour.

Knockel said that he has not been able to analyse these cross-border browsers for security and privacy issues, but he pointed to previous Citizen Lab research on the Baidu Browser, which did not find anything related to phishing. But it did find that the full URL of every site a user visited was sent to Baidu, even if the site was encrypted via HTTPS.

Knockel suggested that practices like these should be enough to give people pause.

“Even if Qingsou and Linghu were not outright phishing operations, if their behaviour is in keeping with other Chinese browsers, then they would still be collecting enough information about your browsing habits to be unsafe to use,” he said.