What the demise of music streaming platform Xiami says about China’s internet industry

- Once a leader, Xiami saw its monthly active users (MAUs) fall to 22.4 million by October 2020, a tiny fraction of the 450 million for Tencent’s three music apps

- Founder Wang Hao’s laid back style was reflected in Xiami’s philosophy of focusing on the music first but it may have also contributed to the decline

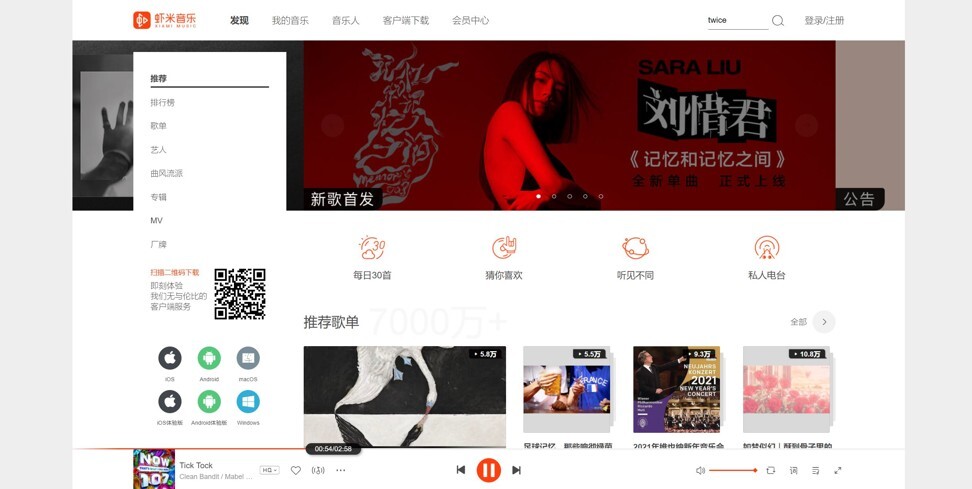

Xiami Music, the pioneering Chinese music streaming service owned by Alibaba Group Holding (which owns the Post), will close next month after management admitted it missed “crucial opportunities” in the battle with rival Tencent Music.

The story of Xiami is a cautionary tale of how a new product can win the hearts and minds of users but still fail in the marketplace despite being part of a much bigger corporation with deep pockets.

It also reminds many of a time when the Chinese internet was less concerned about making money and more focused on building businesses with innovative ideas.

Xiami went from one of the top streaming platforms a few years ago to a distant laggard, with monthly active users (MAU) falling to 22.4 million by October 2020, a tiny fraction compared with an MAU of more than 450 million for Tencent’s three main music apps, according to analytics firm Trustdata.

“We failed to satisfy the diversified needs of our users by acquiring proprietary music content. This is our biggest regret,” Xiami said in a statement last week.

When asked for further comment, Alibaba referred to Post to the statement issued by Xiami.

On social media, loyal Xiami users expressed grief that their beloved music app was coming to an end. “Xiami’s closing is really affecting me emotionally,” one user commented on Xiami’s official account after the announcement was posted on Weibo, China’s equivalent to Twitter. “I will always love you,” the message added.

Another user conveyed his feelings by posting a screen capture of Xiami’s user interface design, which featured a vintage-cassette tape labelled with a song by the late singer Leonard Cohen. “Such a delicate and artistic user interface will not be found elsewhere,” the user said.

Humble beginnings

The original concept for Xiami was thought up by a group of music lovers in a Hangzhou coffee shop. Officially launched in 2008, it would become one of China’s earliest platforms to provide on-demand music streaming.

Originally called EMUMO, for “earn music and money”, Xiami rapidly gained a reputation among Chinese fans of Western rock music.

Indeed, its founder Wang Hao played in a rock band in university and today goes by the Weibo username of Pumpkins, reportedly because he is a big fan of US rock group Smashing Pumpkins. However, Wang last week shrugged off the demise of his creation.

“If it’s gone, it’s gone,” he posted on Weibo in response to the outpouring of user regret over the closure. Wang and his family have since moved to Phuket, Thailand, a tourist destination popular among Chinese.

His new life is far removed from the notoriously long working hours prevalent at Chinese tech companies. Two days after the announcement of Xiami’s closing, Wang posted on Weibo a photo of a telescope set up by a swimming pool, with the caption: “[I will] contemplate the stars tonight”.

Wang’s laid back style was reflected in Xiami’s philosophy of focusing on the music first. It may have also contributed to the decline of the company as Wang and his founding team may not have easily adapted to Alibaba’s culture of setting aggressive goals and conducting rigorous performance-measuring, according to Will Tao, an independent consultant focused on the tech industry.

“Xiami was more pure compared to other apps. It felt like a music-dedicated app, it was not that overwhelmed by pop culture,” said Hu Hu, a musician from the northern steel town of Tangshan who promoted his work on the platform.

Xiami had a playlist of over 30 million songs – including Chinese and Western tracks – and more than 40,000 musicians were posting their work across 1,000 genres, some doing so for free as a way to promote their work.

How Tencent came to dominate music streaming in China

By 2017, Xiami led the industry in active users and user streaming time, according to information from Alibaba’s digital media and entertainment business group.

In 2013, Alibaba acquired Xiami for US$20 million but the acquisition was a double-edged sword for the start-up’s founders, who stayed on under the new ownership, according to analysts. While the deal gave them access to a huge marketing machine, they were not aggressive enough in pushing for the resources needed to develop the platform.

“Alibaba’s acquisition of Xiami was not aimed at expanding Xiami’s music business per se, but rather to draw more traffic and users for its e-commerce businesses,” said Zhang Yi, chief executive and analyst at iiMedia Research.

“The fundamental problem for this type of business is that profits can’t cover the expenses on operations, salaries and marketing,” he said. “Many, including Spotify, still struggle to find a profitable business model.”

04:33

Why live streaming is becoming China’s most-profitable form of electronic media

Strategic missteps

Others pointed to strategic missteps as reasons for Xiami’s demise.

Two years after the acquisition, Alibaba hired Gao Xiaosong and Song Ke, two veterans of China’s music industry, to run Alibaba Music, which combined Xiami with another music streaming app called TTpod.

Gao, a popular singer-songwriter and film director, would serve as chairman and Song, formerly with Warner Music and co-founder of Chinese pop-music label Taihe Rye Music, was to be chief executive.

However, neither had much experience in product development or the internet industry and they faced a formidable competitor in Tencent, which had expanded aggressively into music streaming.

NetEase’s music app steps up moderation of comments targeting depression

Under Gao and Song, Xiami’s strategy was to bring the entire offline music industry onto its platform, according to Li Qingshan, research director at EqualOcean. “Xiami was ahead of its time,” he said.

Messages sent to Wang and Gao’s Weibo accounts seeking comment were not answered at press time.

However, being pure in functionality and purpose was not necessarily an advantage in a cut-throat market where barriers to entry were low and profitability was hard to come by, especially during the early days when pirated music was rampant on China’s streaming platforms. Then the central government cracked down.

In 2015 Beijing introduced several policies designed to clamp down on unauthorised dissemination of copyrighted music, which was costing the local music industry 1 billion yuan (US$154 million) in revenue losses per year, according to iiMedia Research.

The move triggered a scramble among major music streaming operators to acquire exclusive music rights, which in turn resulted in lawsuits between the different platforms over alleged copyright infringement.

Tencent, China’s giant in gaming and entertainment, came to the fight with blank cheques to protect its grip on music streaming, which at one time had it controlling more than 60 per cent of exclusive music copyright in the country.

NetEase’s music app steps up moderation of comments targeting depression

In 2016, Tencent folded QQ Music, Kugou and Kuwo into Tencent Music Entertainment to strengthen its hand in the fight for market share.

The following year, Tencent paid about US$3.5 billion for exclusive Chinese copyright to the playlists of the world top record label Universal Music Group.

It also invested heavily to acquire exclusive copyrights to songs from Sony Music and Warner Music, the world’s second and third largest record companies respectively.

02:20

Hong Kong record collector’s search for the purest sound

Several years earlier, Baidu had settled a copyright infringement lawsuit brought by the same three music majors, ending years of legal battles that went all the way to the Supreme People’s Court. Baidu’s landmark case, where it agreed to pay royalties on music streamed by its users, paved the way for China’s clean up of pirated music.

However, the ensuing tussle among music platforms for copyright forced China’s National Copyright Administration (NCA) to intervene in September 2017. After mediation by the NCA, Tencent, Alibaba and NetEase reached agreements to share up to 99 per cent of their copyrighted music content.

But the 1 per cent that remained exclusive was what really mattered, according to Li from EqualOcean. “One per cent of Tencent Music’s archive of 40 million copyrighted songs translates to 400,000 songs, enough to cover mainstream music fans,” he said.

Losing out

Analysts believe Xiami was the ultimate loser from the policy-triggered sector upheaval, gradually ceding its market dominance to Tencent and NetEase Music, which was established by Hong Kong-listed NetEase in 2013.

“The problem wasn’t lack of money,” said Tao, the tech consultant. Rather, “Xiami’s team failed to convince Alibaba’s board of the need for enough resources to win the copyright fight”.

In 2016 Wang was seconded to DingTalk, Alibaba’s corporate messaging app, but he ended up leaving the company and currently does not own any of its shares, according to one of his recent Weibo posts.

“I made many complaints about things inside the company when I was there,” he said in the post, which also voiced support for Alibaba in its antitrust case brought by the Chinese government.

01:45

‘I can make music anywhere’: Chinese man whistles his way to online fame

As part of Alibaba’s larger business empire, Xiami’s financials were not publicly released, making it hard to determine its health before closure.

In any case, analysts said the impact of its closure on the music streaming market is minimal. “It’s more tinged with a feeling of reminiscence,” Zhang said.

Pulling back

In what Zhang said was a signal that Alibaba wanted to pull back from Xiami, the company and YunFeng Capital, a venture capital firm co-founded by Alibaba founder Jack Ma, invested US$700 million in NetEase Cloud Music in September 2019.

“The strong are becoming even stronger,” Trustdata said in a report, adding that the largest platforms are increasingly encroaching into the streaming time of users on smaller platforms, pointing to future consolidation in the 14-billion-yuan market.

The old Xiami team will shift its focus to a new music management and distribution platform, Conch Music, and work with other platforms including Alibaba’s own Taobao marketplace and Tmall Genie, the company said in last week’s statement.

While fans of the old Xiami are taking it badly, some performers who distributed their work via the service are more laid back about it, much like the founder was. Asked what he would do with his demo tapes, the steel town musician Hu Hu said he would leave them there to “disappear” along with Xiami.