Why immuno-therapy is leaving markets abuzz across the world

Research into the field that uses the body’s own immune system to help fight cancer creating huge interest among the investment community

The biotechnology sector’s fastest-growing segment, immuno-oncology, has become the hottest buzzword for investment in Asia.

The field, that uses the body’s own immune system to help fight cancer, has seen two mega acquisitions in the United States in recent months.

And Hong Kong stock exchange is now tuning into its strong future, with Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing (HKEX) already agreeing to revamp listing rules that will fast track applications by firms linked with the sector to help more innovative drugs and medical devices developers go public as soon as early this summer, and raise much-needed development cash.

The whole concept of the body’s immune system being able to fight cancer has created huge excitement among the investment community.

Some of the sector’s more promising companies have already seen dramatic rises in their share prices.

The most marked has been Nanjing-based Genscript Biotech, a life sciences research services provider and cancer treatment developer, which has enjoyed a 63.5 per cent surge since December after winning a US$350 million investment from Johnson & Johnson offshoot, Janssen Biotech, to jointly develop a treatment for a type of blood cancer called multiple myeloma.

Genscript shares have rise tenfold since it first announced 12 months ago that clinical research on its “proprietary” technology, in collaboration with hospitals in China, had yielded “promising” results at the pre-clinical trial stage.

Multiple myeloma afflicts up to five individuals in every 100,000 in different parts of the world.

Janssen’s technology licencing and co-development deal – its first in China – came after a five-month due-diligence exercise that saw it sending 90 people to Nanjing to examine data results on Genscript’s “LCAR-B38M” chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell technology, said Genscript vice-president of strategy Zhu Li.

T-cell technology is a rapidly emerging form of cancer treatment, primarily for blood cancers such as leukaemia and lymphoma. It is a type of treatment in which a patient’s T-cells (a type of immune cell) are changed in the laboratory so they will bind to cancer cells and kill them.

“This deal is unprecedented in China, where a major international pharmaceutical firm essentially agrees on joint decision making [in a joint project with a much smaller partner].

“Both parties are looking towards long-term achievements,” he told the China Healthcare Investment Conference in Shanghai last month.

That share agreement covers development and manufacturing outlays, and profits and losses – 70 per cent Genscript, and 30 per cent Janssen – within China market, and a 50/50 split in markets outside the country.

The technology received China Food and Drug Administration approval last month to start clinical trials, the major milestone in any new drug’s development.

“Having international partners, particularly a well-known multinational pharmaceutical firm [such as J&J], validates [the Chinese firm’s achievement] in that it proclaims to the world that [its] drug has been accepted by others,” said Shanghai-based Helen Chen, head of L.E.K. Consulting’s China bio-pharmaceuticals and life sciences practice.

The achievement is being viewed as a landmark example for Beijing’s ambitious “Made in China 2025” plan, which strives to garner the acceptance of Chinese innovation globally, she added.

Janssen’s investment came four months after Gilead Sciences’ US$11.9 billion acquisition of fellow California-based Kite Pharma, whose US$373,000-per-patient Yescarta CAR-T treatment in October became the second gene therapy approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and the first for certain types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The acquisition price was a far cry from Kite’s mid-2014 initial public offering on Nasdaq that gave it a market value of US$620 million.

The first US FDA approval was received in August last year by Swiss-based pharmaceutical giant Novartis, on its Kymriah CAR-T therapy which treats a common form of childhood leukaemia. The treatment is not cheap, at US$475,000 per patient.

Janssen’s deal with Genscript was closely followed by New Jersey-based global bio-pharmaceutical major Celgene Corporation’s US$9 billion acquisition of Seattle-based CAR-T cell-based blood cancer therapies developer Juno Therapeutics in January this year.

Juno debuted on Nasdaq late 2014 with a valuation of US$2.2 billion.

“When [these kinds of ] major acquisitions start to happen, everyone thinks there will be more, so investors bid up the prices on all the other firms they think may be the next targets,” said Brad Loncar, chief executive of US-based private biotech-focused investment firm Loncar Investments.

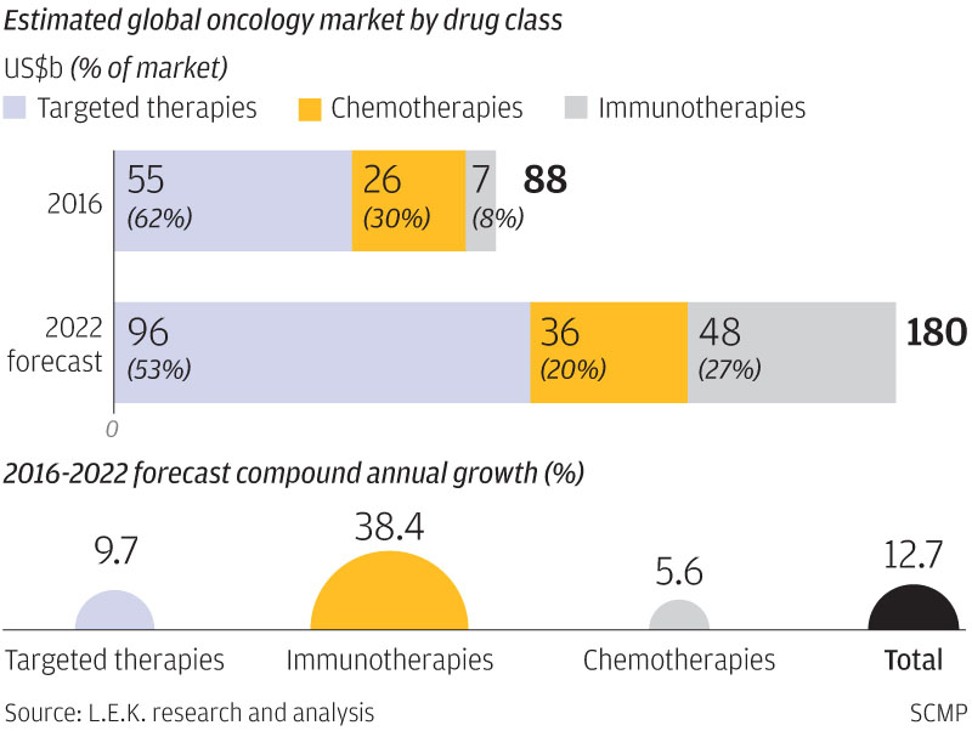

L.E.K. Consulting predicts the global immuno-oncology therapy market could mushroom sevenfold, from US$7 billion in 2016 to US$48 billion by 2022, representing a 38 per cent compound annual increase.

It could make up 27 per cent of the US$180 billion entire cancer treatment market by 2022, up from just 8 per cent in 2016, when it was worth US$88 billion.

Oncology in general is the hottest area of pharmaceutical research and development

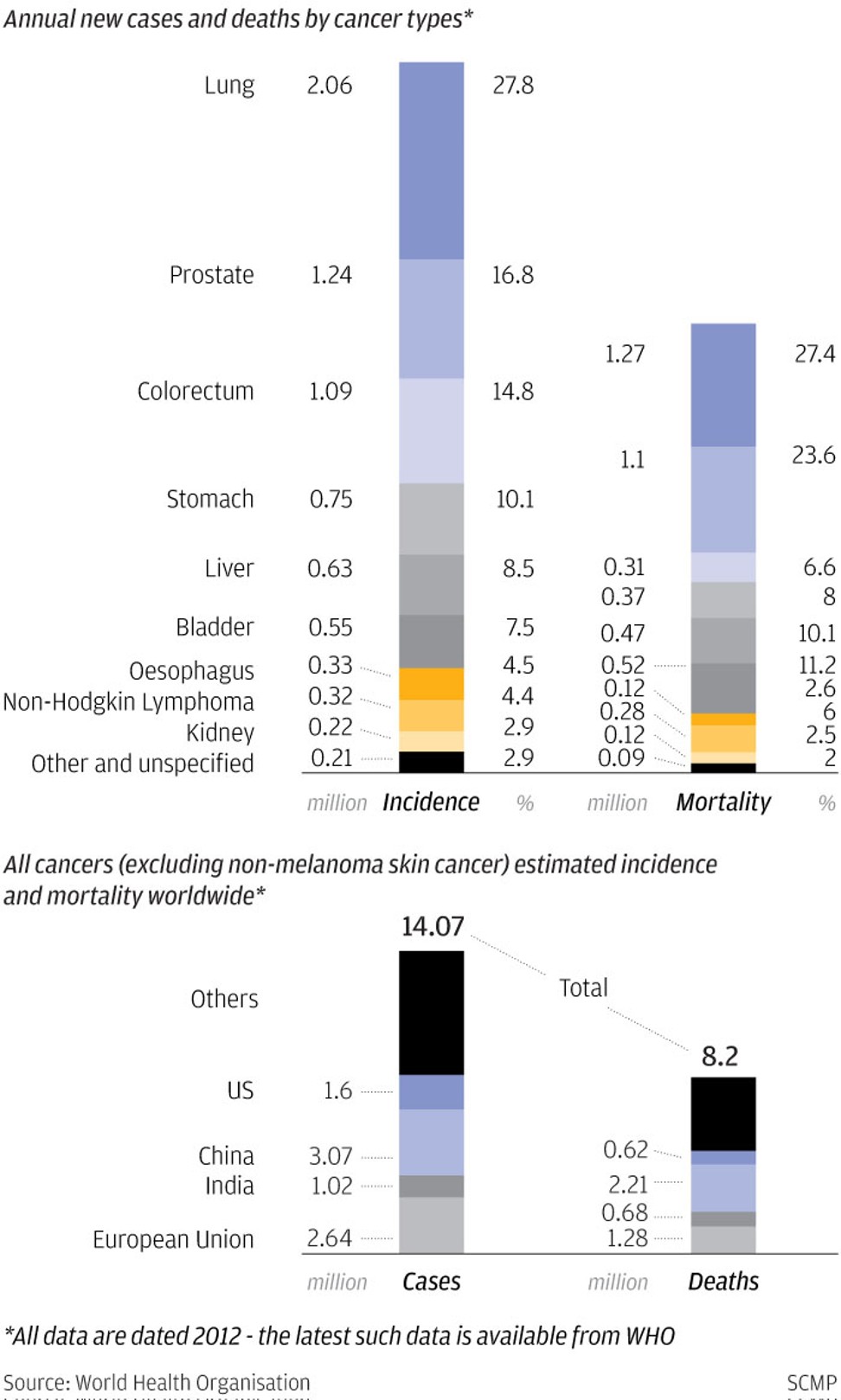

“Oncology in general is the hottest area of pharmaceutical research and development,” L.E.K.’s Chen said, adding a recent survey of 4,186 companies by the Washington-based international body Biotechnology Industry Organization found that they had 1,640 ongoing clinical oncology programmes, more than three times the next therapeutic area.

While their dollar revenues will rise between 2016 and 2022, L. E. K expects the market share of more traditional chemotherapies – the treatment of cancers by the use of chemical substances and other drugs – to fall to 20 per cent from 30 per cent, while targeted therapies could slide to 53 per cent from 62 per cent.

Chemotherapy can also kill normal cells while eliminating cancer cells, while normal cells can survive targeted therapy which eliminates them or at least suppresses their growth.

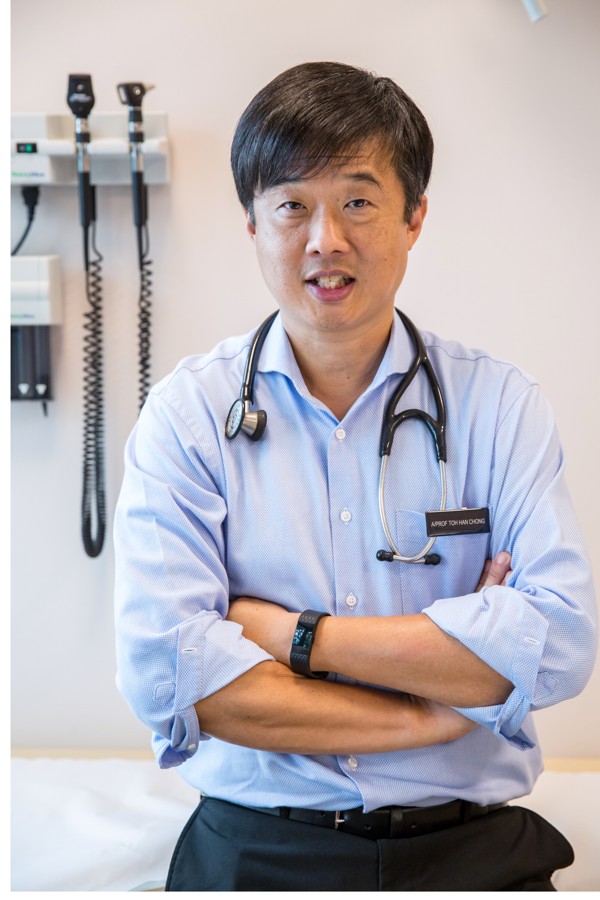

“Twenty years ago, nobody would have believed you could use your own cells to fight cancer … people only knew of surgery, chemo and radiotherapy. Immuno-therapy is something completely new,” says Singapore-based Tessa Therapeutics’ chief medical officer, Toh Han Chong.

Tessa has been mulling a listing on the Hong Kong stock exchange or on the tech-led Nasdaq in the US, to raise further funding for its various immuno-therapy development programmes, but has yet to make a final decision.

“Investors in Asia understand cancers that are more prevalent among Asians better, and companies working on treatments for them better … so Hong Kong is a strong potential option for us. Having said that, Nasdaq has been around a lot longer for biotech listings, and has a lot more depth,” Toh said.

“Hong Kong’s announcement [to allow pre-profit biotech listings] will stimulates drug development in Asia, and we really need that … few people understand that the [world’s] biggest cancer burden is in Asia and the rate of new cancer diagnosis growth in Asia surpasses that of the US, as its population is ageing faster.”

Toh is also deputy director of the National Cancer Centre Singapore, and led a phase-two immuno-therapy trial there on 35 nasopharyngeal (a rare type of head and neck cancer) cancer patients which showed “significantly higher two-year overall survival rates compared with trials in similar settings”, Tessa said.

The cancer mostly afflicts people living in Asia, or has its origins in South China and Southeast Asia.

Tessa raised US$130 million in December in a fundraising round led by Singapore sovereign fund manager Temasek, and is “more than halfway through” a phase-three clinical trial which will treat over 300 patients across seven hospitals in the US, and 23 hospitals in Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand and Taiwan.

It is the only phase-three trial of a T-cell therapy for solid tumours anywhere in the world, according to Toh, and results success is required before any commercial launch could be allowed.

The treatment requires the extraction from patients of “T-cells” – types of white blood cells that form part of patients’ immune system.

The cells are “built” from a few hundred thousand in the blood sample, to a billion, while being “targeted” to give them the capability to recognise and attack cancer cells, when they are reinfused into the patients’ body.

“When these cells are taken out of the body, they are not very strong and are unable to tackle very specific [targets] – so you need to train them to be more specific, to be able to hit those targets,” said Toh. Such “virus-specific” T-cells are capable of identifying viral markers on the surface of tumour cells in virus-linked cancers.

Tessa is the first international partner of the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy in the US, which is backed by a US$250 million donation from Napster co-founder Sean Parker. Another of Tessa’s research partner is Houston-based Baylor College of Medicine.

Tessa aims to launch at least four more clinical trials in the next 12 months on head, neck, cervical cancers, which like nasopharyngeal cancer, are also virus-driven.

“There are no approved T-cell therapy treatments for solid tumours, even though they make up around 85 per cent of cancer incidences globally,” said John Connolly, Tessa’s chief scientific officer.

“We believe our platform can make a significant impact in addressing this large, unmet need.”

Only one in 10 drugs registered for phase one trials make it to commercial success, according to the Biotechnology Innovation Organisation.

For oncology drugs in phase three trials, only 50 to 60 per cent succeeded to commercialisation, said Bao Jun, the chief business officer and acting chief financial officer of Beijing Shenogen Pharma Group.

“We will have an idea [of the trial’s results] by the end of next year – whether we are looking at something very exciting,” Toh said of the nasopharyngeal cancer trial.

“As with all clinical trials, not everybody will succeed – but we are hopeful.”