Asia’s lonely youth are turning to machines for companionship and support

With more people in China, South Korea and Japan remaining single and living alone, AI companions fill an emotional gap

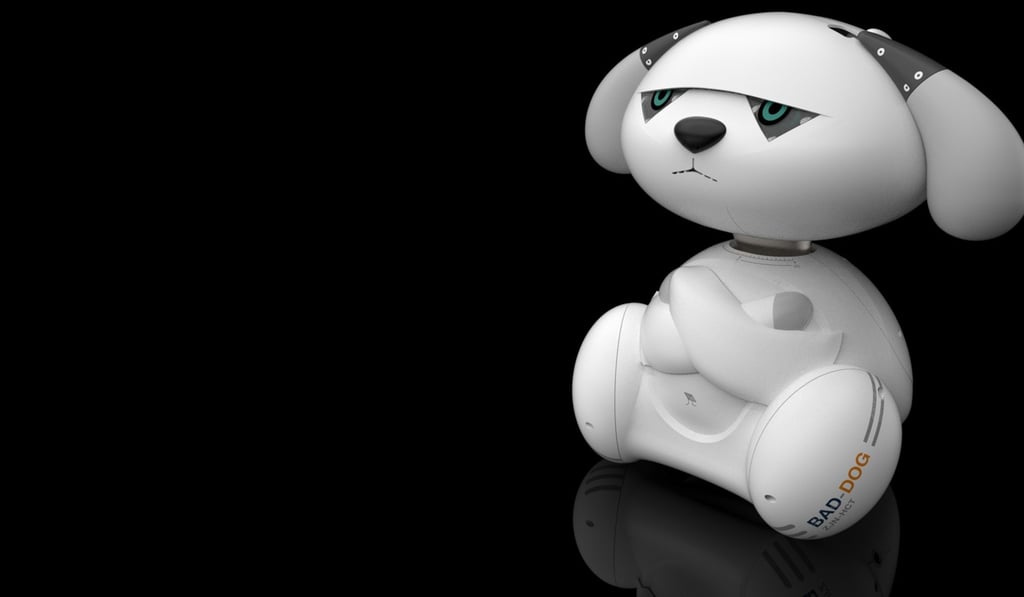

In May, China met Fuli, a foot-tall, plastic robot dog that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to provide emotional support to its owners, while also requiring care and attention of its own.

Something of a cross between Japan’s Paro, the baby harp seal which can ‘coo’ electronically to the elderly, and a Tamagotchi, Fuli is self-mobile and equipped with sensors that enable it to monitor an owner’s biometrics, information the robot then uses to gauge the keeper’s mood and respond accordingly.

According to its creator Zhang Jianning, the digital canine also has the ability to nag its owner to complete chores, receive their mail when they’re away, and contact emergency services if it detects the owner has fallen ill.

Zhang’s robot version of man’s best friend is the latest in a growing line of AI-powered personalities to hit the tech world in Asia in recent years. At a time when more people in China, South Korea and Japan are remaining single and residing alone for longer, companies have been developing new ways to fill the emotional gap. From robotic pets to virtual reality girlfriends, East Asia’s new AI companions are taking digital assistance a step beyond the practical functionality of Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa – and it looks like consumers are opening both their hearts and wallets.

“Some of the younger generation feel more comfortable communicating with computers than humans,” said Kitty Fok, the Beijing-based managing director of IDC China, a tech industry analysis firm. As the social and economic forces behind East Asia’s loneliness problems continue, the market for AI companions is likely to expand, Fok said.