Exclusive | A chance conference meeting helped Grab seal Uber merger although regulators may still have last word

Both Singapore and Malaysian regulators are analysing the merger

When Grab chief executive Anthony Tan travelled to the US for a conference last year he had no idea that he’d be one step closer to ending a bitter ride-hailing war between Grab and Uber that had spanned the previous five years, said Tan in an interview with the Post, explaining for the first time how the deal came about.

Tan ran into several board members of Uber, who asked him how Uber was doing in the region.

“We gave them our input and eventually they asked, ‘Why are we killing each other? Why don’t we work together and create value?’ To us, that was a [good] idea and it was how it started,” Tan recalled.

Subsequently, Tan sought the support of Grab’s shareholders for a merger. Uber’s management was also positive about the deal, which was similar to the merger between Uber China and Didi Chuxing in August 2016.

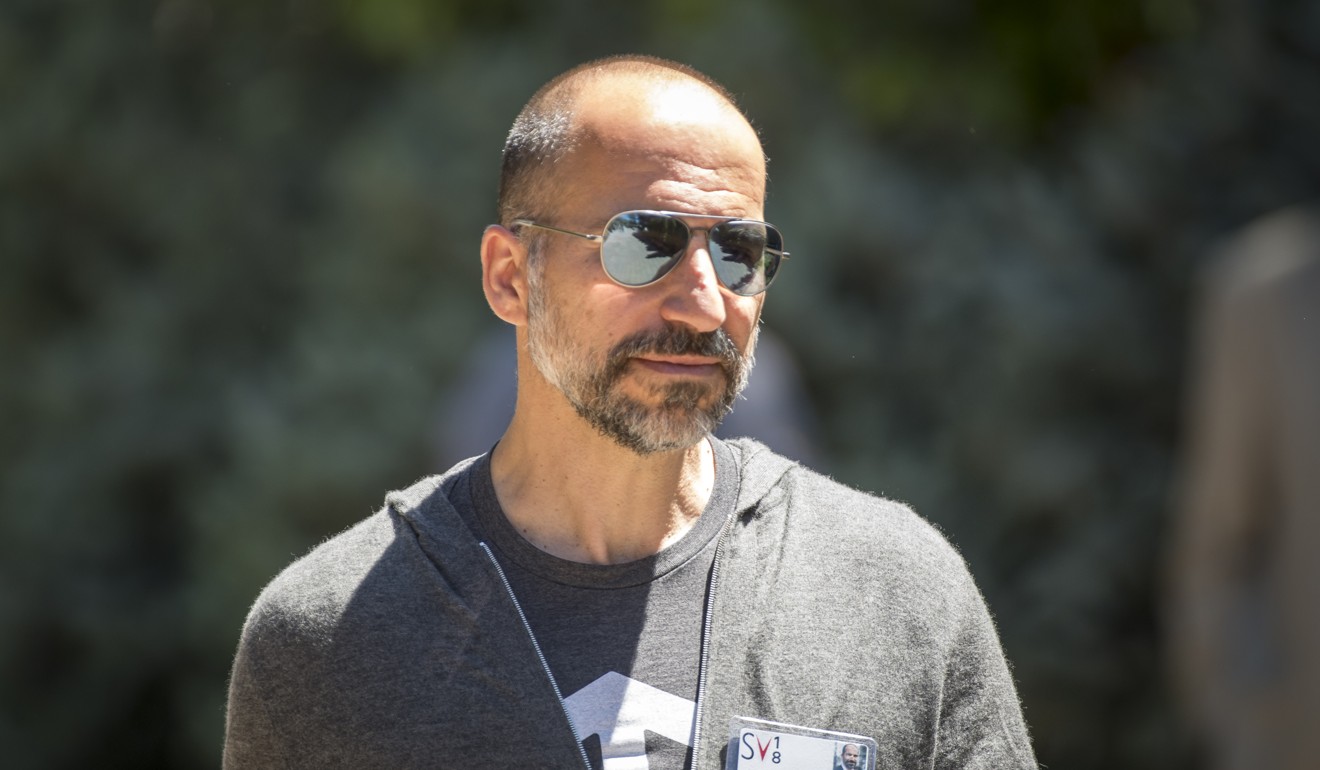

Tan then met one-on-one with Uber chief executive Dara Khosrowshahi.

“We tried to understand each other and build trust, and over time because of that trust we moved to talking about the deal,” Tan said.

Uber did not immediately respond to enquiries about the process of the merger.

Both companies merged in March, and Uber’s app ceased to work in Southeast Asia two weeks later, making Grab the dominant app across the region, where it faced few competitors apart from Go-Jek in Indonesia.

However, the deal has since drawn regulatory scrutiny across the region. Earlier this month, Singapore’s antitrust watchdog, the Competition and Consumer Commission of Singapore (CCCS), released findings from its investigation, stating that the merger “substantially lessened competition” and proposed financial penalties and solutions to restore market competition.

The Malaysia Competition Commission (MyCC) followed in the footsteps of the CCCS just days later, stating that it will begin an investigation to assess monopoly risk following Grab and Uber’s merger, after it received multiple complaints about price surges.

But corrective action may be too late, according to Yang Nan, an assistant professor from the National University of Singapore’s business school.

“It is hard to rectify the damage to consumers after the deal has already been done,” Yang said. “The remedies suggested will not be fully able to capture the gains made by Uber and Grab from the merger.”

The CCCS findings showed that both companies knew that Uber would not have withdrawn from the region had the merger not taken place, which means that the ‘failing firm defence’ for the merger does not hold, Yang said.

“Grab was ready to take the hit [from regulators], they were prepared for such an outcome because when you have a fiercely-contested duopoly move to become a monopoly, that’s still huge,” Yang said.

“Pulling out of a market and merging with a local player is strategic for Uber, who exited China in a similar manner. As they still have a stake in Grab, Uber benefits from whatever business is still conducted in that market.”

Yang pointed out that the worst case scenario would be if CCCS forces Uber to divest their assets from Grab and look for another buyer to maintain competition in the market, but added that this outcome is unlikely.

“The ride-hailing market still has huge potential for other players, especially if CCCS dismantles exclusivity contracts between Grab and taxi operators. That way other players can still amass their own fleet,” he said.