How WeChat became China’s everyday mobile app

Tencent has frequently added innovations to WeChat, designed to drive growth and loyalty, the latest being mini programs

Many people outside China either still haven’t heard of WeChat or they think it’s the country’s equivalent of popular messaging service WhatsApp or social media giant Facebook. For many people in China, WeChat is much more – it is not an overstatement to say it’s an indispensable part of their everyday lives.

WeChat, or Weixin as it’s known in China, began life in a southern corner of the country at the Tencent Guangzhou Research and Project centre in October 2010. Since then, it has grown into the most popular mobile app in the country with over 1 billion monthly active users who chat, play games, shop, read news, pay for meals and post their thoughts and pictures. Today, you can even book a doctor’s appointment or arrange a time slot to file for a divorce at the civil affairs authority.

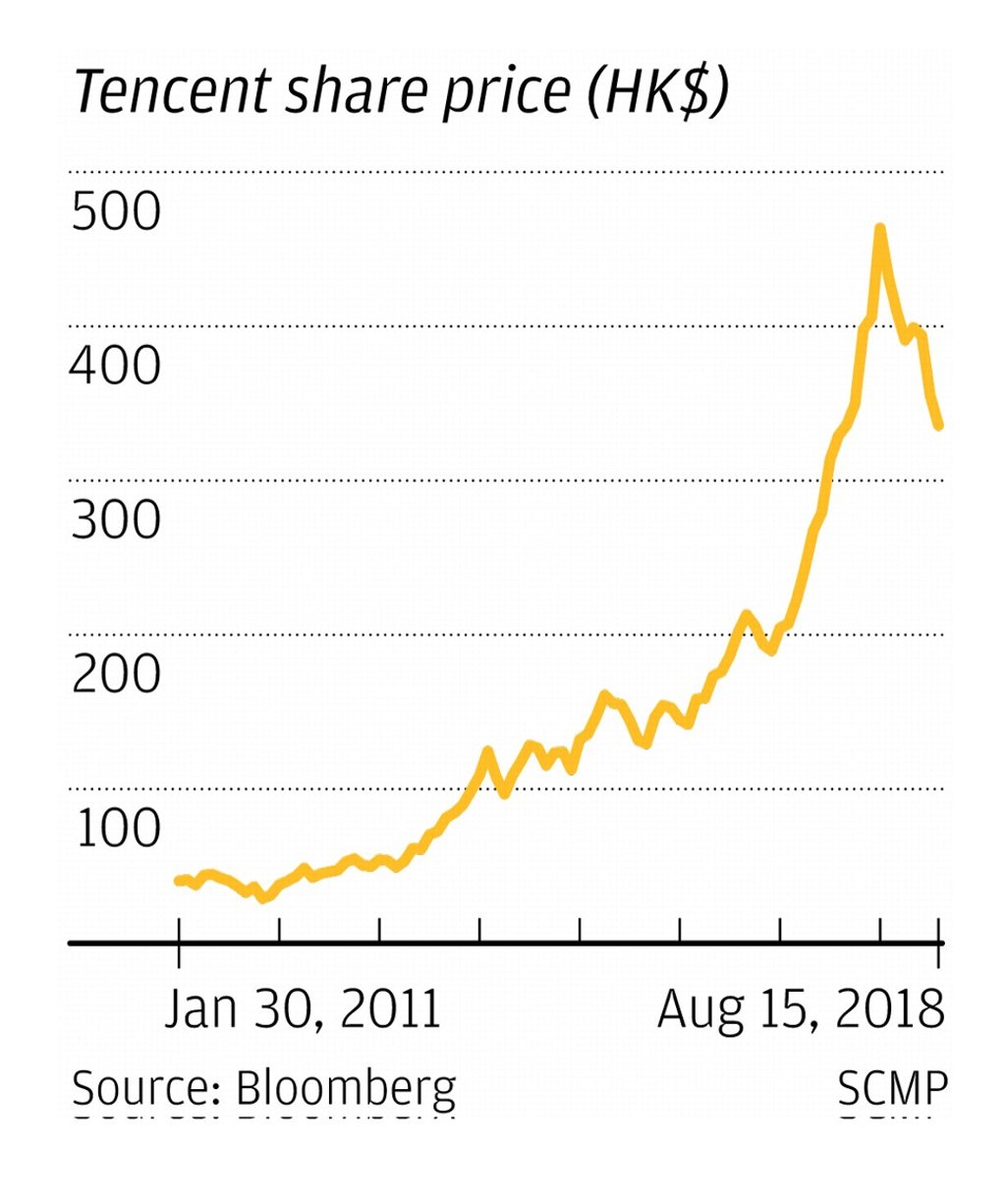

The seven-year-old app has also laid the foundations for stellar growth at Shenzhen-based Tencent Holdings, the tech giant behind WeChat, turning it into one of the most influential companies in China and grabbing the attention of global investors. Since the official launch of WeChat in January 2011, Tencent’s market capitalisation has risen over tenfold.

Yet, the company has hit a speed bump. Tencent has lost 29 per cent since a peak of HK$476.6 a share in January this year to trade at HK$336, erasing US$170 billion from its market value as of Wednesday’s close. Even before this sharp fall, some commentators had been asking whether Tencent has “lost its dream”, by focusing on growth through investment rather than the type of organic innovation that led to the creation of WeChat.

After the market close on Wednesday, Tencent reported a 2 per cent drop in second-quarter profit on lower gaming revenue and investment-related gains. Net income fell to 17.9 billion yuan (US$2.6 billion) in the quarter ended June 30, compared with the 19.3 billion yuan average of 12 analyst estimates compiled by Bloomberg. Sales were 73.7 billion yuan, missing analyst estimates.

Tencent’s overseas counterpart Facebook, with 1.47 billion daily active users (DAU) and 2.23 billion monthly active users (MAU), experienced a stock price loss of over 20 per cent after announcing its slowest quarterly user growth since 2011 in its second quarter earnings report in July.