Opinion | Policymakers are catching up with innovation – but more needs to happen for global tech to thrive

- The Covid-19 pandemic has boosted the digital economy and the appreciation of the strategic use of data

- International and cross-border e-commerce is one area that could prove transformative, offering new opportunities for retailers willing to go digital

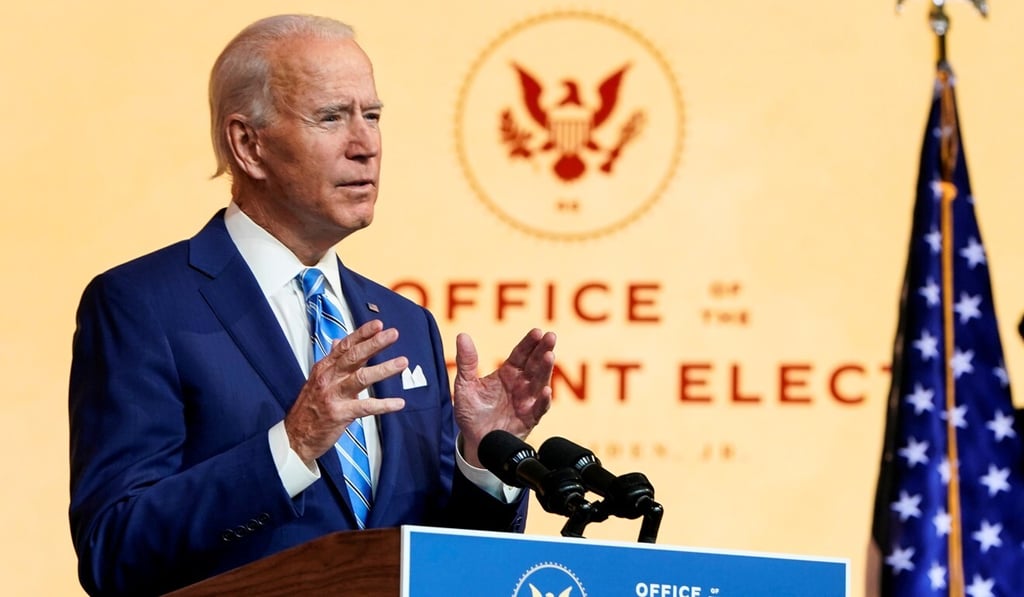

The European Union has set out plans to reset relations with the United States when Joe Biden enters the Oval Office next year. The proposals include a “transatlantic technology space” to shape regulatory frameworks across global tech and address global challenges. Brussels’ proposal reflects rising tensions in diplomatic circles on technology and data issues.

Speaking at the Asia House Global Trade Dialogue in Singapore last year, Arancha Gonzalez, then executive director of the International Trade Centre, colourfully revealed the unanswered questions on tech and data driving debate at the World Trade Organization. “Where will data sit? Who will own it? How will we protect it?” are common concerns raised among WTO members, Gonzalez said.

Answering those questions is a work in progress, but pressure is mounting. The Covid-19 pandemic has boosted the digital economy and the appreciation of the strategic use of data. This has raised the stakes in rivalries for global tech and data dominance both at the corporate and at the state level.

The pandemic has brought about lasting economic change. While areas such as physical retail, hospitality and travel have been devastated, online entertainment and e-commerce have surged, with consumers shifting online and spending at record levels.

International and cross-border e-commerce is one area that could prove transformative, offering new opportunities for traditional retailers willing to go digital. The numbers coming out of China bear this out.