The rise and fall of Secoo: how China’s top luxury retailer fell off the catwalk after glory days of US$140 million Nasdaq IPO

- Secoo rose from a second-hand handbag shop into China’s largest luxury goods exchange for individuals

- Analysts say a change of heart on e-commerce channels by global luxury brands, more competition, and the pandemic have all been challenges

The spectacular fall from grace of China’s top luxury retailer Secoo offers a cautionary tale about how many companies which were once seen as rising stars in a high-growth market are now facing the harsh reality of increased competition and weak consumer spending in a slowing economy.

Secoo, started by Chinese entrepreneur Richard Rixue Li and enthusiastically backed by private equity capital, rose from a second-hand handbag shop into China’s largest luxury goods exchange for individuals with a 2017 initial public offering on Nasdaq raising US$140 million.

However, since then the luxury platform has lost its way. Although its main digital app remains in operation, a plethora of complaints from consumers and vendors on social media, combined with a now-withdrawn bankruptcy filing, have crippled the company’s public image.

In a 17-year-old shopping centre in Shanghai, Secoo’s brand new offline store can be seen perched on the fourth floor, with sections including menswear, womenswear, children’s clothing, handbags, authentication services and others.

China tries to calm jittery investors after shock of Shanghai lockdown

But few customers could be seen when the South China Morning Post visited the store on two separate occasions earlier this year, before Covid-19 lockdowns hit large swathes of Shanghai. The outlet is one of 300 offline spaces that were planned by the company in the country through direct franchises and joint partnerships in late 2021. So far, only two of them – in Shanghai and Chongqing – have materialised.

A customer service reply to a question sent via the company’s app said that the Shanghai outlet is currently undergoing a “refurbishment upgrade” whereas the Chongqing space is undergoing an “adjustment”.

A review section for one of its stores on a third-party app is filled with customer complaints. “It doesn’t deliver, doesn’t return, when I called, it always says ‘system upgrade’, what a con company”, one of the negative reviews states.

Multiple calls to Secoo by the Post to get its comment on questions raised in this article were unanswered as of publication.

Long Zheqing, a consumer based in China’s central Changsha city, has been waiting for a refund from the e-tailer, which sells both new and used luxury goods, for more than half a year.

Shanghai post-lockdown sees consumers queue up at LV, Prada, other luxury stores

“Victims who are close to the Beijing headquarters may have gone there in person to get their refunds much faster, but it’s hard for people like me who are far away,” Long told the Post via messaging platform WeChat. Even though she is still waiting for the refund, Secoo’s customer service continues to call her up for promotional seasons, she said.

In another sign of trouble for Secoo, the Beijing parent firm was forced to pay up to 17.4 million yuan (US$2.6 million) of debt to Shanghai Secoo E-commerce, one of its subsidiaries, by a Beijing court in May 2022, according to business intelligence platform Tianyancha.

The current state of affairs is a dramatic turnaround for a company that once rode the crest of China’s e-commerce and second-hand luxury sales wave. Founded in 2008 by Li and Huang Zhaohui as a trading company, it pivoted towards luxury e-tailing in 2011, attracting an array of well-heeled investors in its early years, including IDG Capital and Bertelsmann Asia Investments.

Clinics, car dealers snap up prime retail space as luxury brands exit

Li said that with strong partners Secoo would be able to “expand and deepen its market presence not only in China, but across the globe”, in a statement in 2018.

Former employees the Post spoke with for this article, talked about their experiences with the company in terms of “before” and “after” the Nasdaq IPO.

One former employee, who did not want to be identified for fear of reprisals, who joined Secoo’s Italy office a few months before it went public, said the team in Italy grew to around 40 people at its largest. “The company was growing at high-speed in 2018, we had money, people and know-how,” she said, adding that they built a platform for European vendors to support the buyers boutique business and helped over 100 boutiques sell on Secoo.

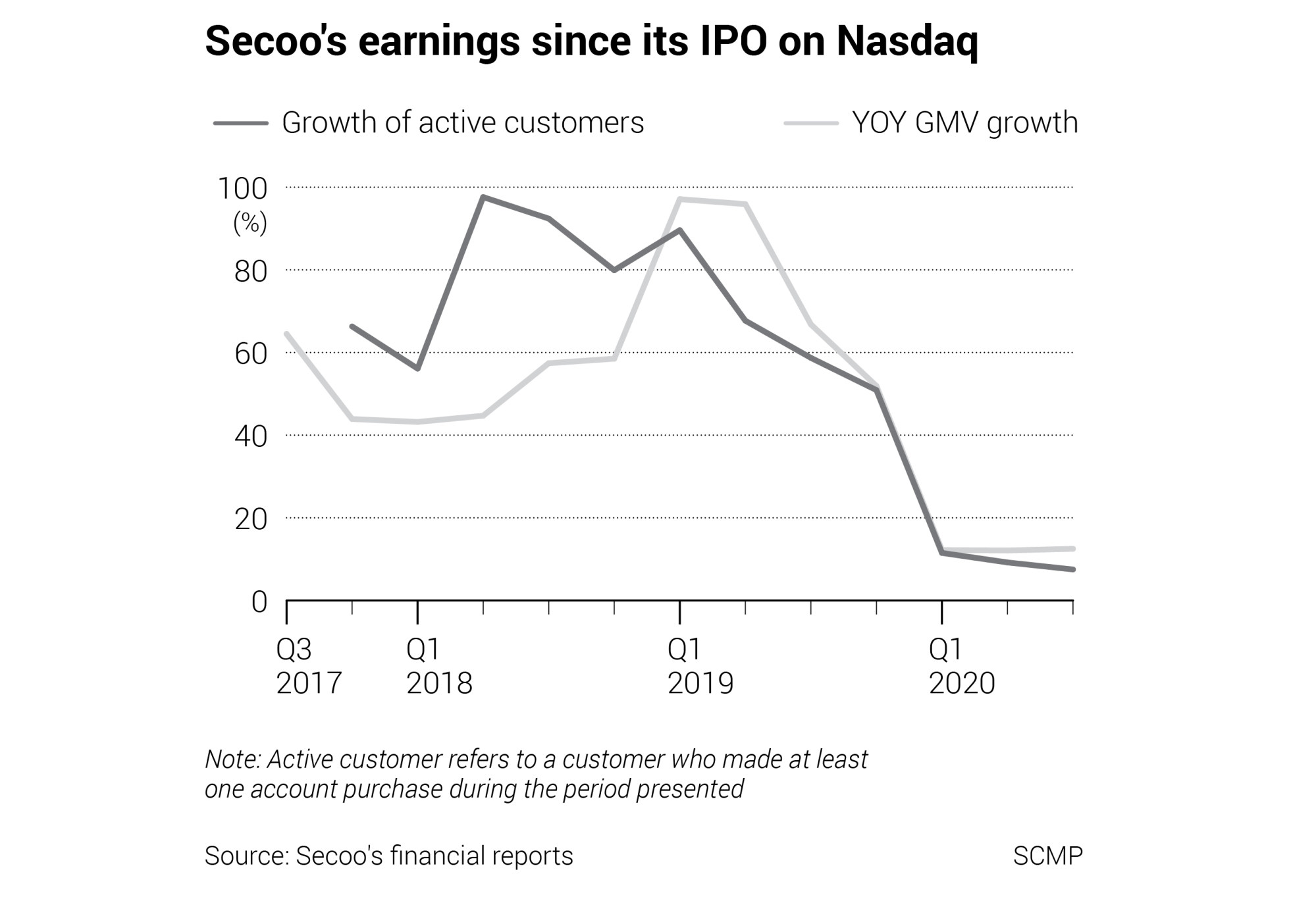

According to Secoo’s financial results, the company as a whole experienced high growth in revenue and the number of active customers doubled almost every quarter in mid 2018 and early 2019 until the growth gradually slowed in late 2019.

By the end of 2019, although the number of orders remained largely the same, the Italy team felt that it was proving tough for Secoo’s China team to prove it could deliver payments to European vendors and brands, the employee said.

Another former employee of the Italy office, who also requested anonymity for fear of retaliation, said Secoo still owes her around 9,000 euros (US$9,500) representing two months’ salary, severance pay and meal ticket subsidies from last year. She quit and took up a new job offer after Secoo stopped paying her.

5 held as Hong Kong customs seizes HK$22 million worth of fake goods

Meanwhile, a third former employee who was part of Secoo’s branding team based in Beijing who also requested anonymity due to fear of reprisals, said he felt issues in 2019 over “management and inventory matters”.

Compared to fellow e-tailers like Farfetch and Net-a-Porter, Secoo had fewer direct partners, and goods sourcing mainly relied on parallel imports and a large network of buyers, which meant expenses were higher.

The anonymous former Beijing employee said Secoo relied on physical stores in Beijing, Shanghai and Chengdu, for stable cash flows, but the sudden disruption caused by the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic across China in early 2020 hindered operations. The three physical stores have all since closed.

In the first quarter of 2020, growth in active customers and gross merchandise value both dropped from over 50 per cent to 12 per cent, according to exchange filings. Growth further declined to single digits until 2021, when after publishing first half results, the company stopped releasing any financial records at all.

Under its 180-day grace period, which ends on June 15, the company will be officially delisted if its closing bid price is not above US$1 per share or higher for at least 10 consecutive business days. As of publication, the company has not yet met this requirement.

But how did it come to this? Analysts attribute the company’s problems to several factors, some beyond its control and some not.

Secoo enjoyed rapid growth before global luxury e-commerce platforms Farfetch and Net-a-Porter entered the market in 2017 and 2019 respectively, and before global luxury brands such as Louis Vuitton and Gucci opened up official e-commerce channels via WeChat mini-programs and Tmall. Secoo also launched before home-grown luxury resellers such as Ponhu and Red Plum were founded. Alibaba Group Holding, which operates Tmall, also owns the Post.

After the pandemic further reduced physical shopping, reluctant luxury brands finally caved in to the e-commerce surge. For example, Gucci chief executive Marco Bizzarri, who once warned that the Kering-owned brand did not want to “certify counterfeiting” in a reference to e-commerce channels, changed course. Domestic competition also increased.

China’s e-commerce giants start sales campaigns for midyear 618 shopping festival

Covid-19 has hastened the convergence of the online-to-offline sales model, said Cai Jinfeng, executive director at Frost & Sullivan’s Greater China office. “Due to Covid-19, many physical stores could not operate, which pushed brands to develop online channels to reach consumers,” said Cai.

But Secoo has also made several business decisions that deviated from its original mission, which was to sell second-hand luxury online.

Moving from a low capital intensive model to a higher-cost one has meant that Secoo has struggled to meet payments to vendors and consumers, according to analysts.

Despite owning what it called “first-in-the-industry” blockchain-empowered authentication services since 2018, Secoo has been accused of selling counterfeit goods. Secoo has either denied these allegations or declined to comment on the matter when speaking to local media.

“For luxury e-tailers, counterfeit and trust issues have always been the industry’s pain points, once controversies over products occur, it can cause huge harm to the credibility of the platform,” said 100EC.com’s Mo. “With the fierce market competition and many other challenges, it will be hard for it to bounce back.”

In March, Shanghai’s social retail sales dropped 20 per cent amid the city’s lockdowns, while wearable goods sales plunged 30 per cent, the lowest of all categories. In April social retail sales for the same category fell 38 per cent. Although Shanghai is gradually reopening after a two-month citywide lockdown, a recovery in consumer sentiment is uncertain.

Secoo’s shares closed at about 26 US cents on Friday, meaning the company only has a few days left to avoid a delisting after June 15. Over the past month, Secoo’s stock has dropped over 20 per cent, and it is now around 97 per cent below its highest point in 2018.

A Beijing-based customer using the handle Yuanyuanlian on social e-commerce platform Xiaohongshu who requested a refund from Secoo after running into a similar problem as Long, is certain that she is not going back.

Despite securing a refund from Secoo after calling 315, China’s official consumer complaint hotline, Beijing’s resident service line, the municipal consumer association, online complaint platform Black Cat and the science and technology commission of Miyun County, she remains upset.

“I will not use the platform again, credibility is very important in online shopping,” she said in a message via the social e-commerce app. “I would trust official websites and physical stores more.”