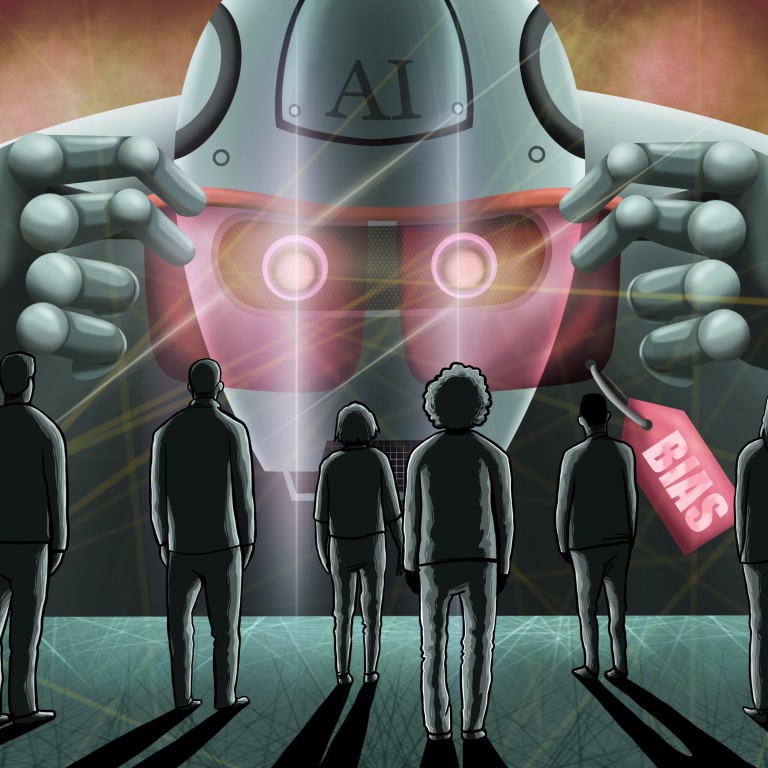

Sexist and racist AI can result in wrongful arrests, fewer job opportunities or even death. Now, more are taking notice

- Researchers have found that social biases can be amplified in AI algorithms that determine access to jobs, health care diagnosis outcomes and more

- Society can only achieve fair AI outcomes if it works as a whole, not just with the effort of a few individuals, one expert says

Three years ago, while testing an artificial intelligence model for automatically labelling images from the web, Jieyu Zhao spotted a trend: it repeatedly associated images of people in kitchens with women, even when they showed men.

Suspecting social biases might play a part, Zhao, then a PhD candidate at the University of Virginia, teamed up with several peers to investigate.

Their findings, published in a 2017 paper, were shocking. Even though images used to train the model showed 33 per cent more women than men in kitchens, the AI more than doubled this disparity to 68 per cent.

“Structured prediction models can leverage correlations that allow them to make correct predictions even with very little underlying evidence,” the researchers wrote. “Yet such models risk potentially leveraging social bias in their training data.”

But so what if a machine mislabels an image of a man cooking as a woman, or a woman brandishing a gun as a man? Such mistakes might not seem like a big deal, but as AI becomes integrated into more aspects of daily life, they can have real implications for many people.

Too white, too male: scientist stakes out inclusive future for AI

Zhao, now pursuing her PhD at the University of California, Los Angeles, is among a growing group of researchers worldwide questioning how social biases, especially those related to gender and race, can be amplified through machine learning systems affecting access to jobs and credit, health care diagnosis outcomes, jail time for criminals and more.

“People used to think that a [machine learning] model would be fairer than humans, who are inherently biased, by learning from data,” Zhao said. “This is not true; we found that the models can still learn to be biased.”

Experts say the quality of the data used to train machine learning algorithms is often to blame.

“The real world is an ugly place – it's made up of human beings who are themselves biased in various ways,” said Feng-Yuan Liu, CEO and co-founder of Singapore headquartered BasisAI. “If you take data from the real world, the data already contains a lot of bias and the AI systems will teach themselves to be biased,” he added.

The form this bias takes may be affected by where the AI developers are based and the available data. A US study published last December tested facial recognition algorithms from 99 developers worldwide and found they generally returned a high number of false positives, wrongly considering photos of two different individuals to show the same person, for East Asian people.

However, for a number of algorithms developed in China – including those by leading facial recognition start-ups Megvii and Yitu Technology – this effect was reversed, showing fewer false positives for East Asian faces than Caucasians in some cases, according to the study by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

In a landmark study in 2018, researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Stanford University also found differences in facial recognition accuracy based on race and gender. The study, which tested commercial facial recognition programs by Microsoft, IBM and Megvii, found error rates of up to 34.7 per cent when classifying images of darker-skinned women by gender, compared to a maximum of 0.8 per cent for lighter-skinned men.

The real world is an ugly place – it's made up of human beings who are themselves biased in various ways.

The researchers pointed out that benchmark data sets used to train algorithms are often skewed demographically. For instance, one gold standard benchmark for face recognition is estimated to be 77.5 per cent male and 83.5 per cent white.

Resulting errors in facial recognition can have “serious consequences”, they wrote. “Someone could be wrongfully accused of a crime based on erroneous but confident misidentification of the perpetrator from security video footage analysis.”

It makes sense to use AI to fight crime

The US tech giants mentioned in the MIT and Stanford study have both commented on the findings. “This is an area where the data sets have a large influence on what happens to the model,” Ruchir Puri, chief architect of IBM’s Watson artificial-intelligence system, was quoted by MIT News as saying at that time. He added that the company had since improved its facial recognition model, not specifically in response to the paper but with effort to address the questions lead researcher Joy Buolamwini had raised.

02:35

Meet the founder of Megvii, one of China’s most ambitious AI startups

Microsoft president Brad Smith also referenced the research in a blog post a few months later. “No one benefits from the deployment of immature facial recognition technology that has greater error rates for women and people of colour,” he wrote in the post calling for more government regulation of the sector. “It’s incumbent upon those of us in the tech sector to continue the important work needed to reduce the risk of bias in facial recognition technology.”

Megvii has been comparably silent. Reports about the study did not include responses from the company, and it declined to comment for this story.

China AI start-up Megvii pushes ahead with IPO despite US blacklisting

Sensetime and Yitu also did not respond to queries on their efforts to minimise biases in AI applications.

No one benefits from the deployment of immature facial recognition technology that has greater error rates for women and people of colour

As coronavirus lockdowns and social distancing measures push hiring online, AI recruitment tools have become more popular than ever.

With many companies using automated systems to filter out irrelevant resumes, unchecked biases could mean some qualified candidates’ applications never make it into recruiters’ hands.

In 2018, Amazon reportedly scrapped its AI recruiting engine which had taught itself that male candidates were preferable after being trained on resumes submitted to the company over 10 years that were mostly from male applicants, Reuters reported, citing people familiar with the matter.

Hiring through a screen could become the new norm in China

According to the Reuters report, Amazon said the tool “was never used by Amazon recruiters to evaluate candidates” but did not dispute that recruiters looked at the recommendations generated by the recruiting engine.

When there are more men than women in a company, a recruitment system fed with this data may mistake the existing gender balance as a result it is meant to replicate, said Dong Jing, an associate professor at the Institute of automation, Chinese Academy of Science.

“It may say, ‘see, my results have a higher proportion of men than women, is this right?’ even though this was never something the designers intended; it was just a feature of the data that the algorithm picked up,” Dong explained, adding that a possible way to correct this was to remove references to gender in online recruitment algorithms.

Chinese internet giant Baidu, one of the few Chinese AI companies to have publicly addressed the topic, said in a report last month that it has been using a self-developed recruitment algorithm since 2015 that avoided bias, “ensuring fair recruitment routines and results, especially in equal opportunities for women”.

People used to think that a [machine learning] model would be fairer than humans, who are inherently biased, by learning from data. This is not true; we found that the models can still learn to be biased.

In health care, where a timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment can make a life-or-death difference, AI can also be a double-edged sword, according to an article published this month in the npj Digital Medicine journal.

Sex-specific biological differences have historically been neglected in biomedical research, with studies mostly focusing on male subjects, the researchers said in the article, noting that more recent research has found differences for chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disorders and mental health disorders.

Should AI help make life-or-death decisions in the coronavirus fight?

Failing to recognise sex-specific differences can kill. For example, 40 per cent of women who experience cardiac arrest do not have chest pain, despite this being considered a “typical” symptom in historical studies primarily based on male subjects, according to an article by US-based movement Women in Global Health last year.

“Basing diagnosis on male symptoms and assuming women experience the same, results in misdiagnosis and mistreatment, and as a direct result, women are more likely to die after a heart attack than men,” the researchers said, citing a study that found women under the age of 45 experiencing a heart attack without chest pain were 14 times more likely to die than men in the same age group with chest pain.

AI is a technology that serves human beings. Up until the day when equality becomes the reality in human society, the technology will still be influenced [by real-world biases]

Huawei and Alibaba had not responded to questions about their efforts to minimise bias in diagnosis algorithms as of publication time.

On the other hand, while diagnosis algorithms can magnify biases they can also mitigate inequalities if designed properly, according to the article in npj.

“The development of precise AI systems in health care will enable the differentiation of vulnerabilities for disease and response to treatments among individuals, while avoiding discriminatory biases,” the researchers said.

Hey Siri, you’re sexist, UN report finds

There is evidence that where potential biases are recognised, they can be reduced in AI.

In the 2017 paper, Zhao and her peers proposed a method that reduced bias amplification by up to 47.5 per cent while still accurately labelling images.

And in an audit published about a year after Buolamwini’s 2018 facial recognition report, IBM, Microsoft and Megvii’s software all showed improvements, with the maximum error rate for darker-skinned female faces more than halving from 34.7 per cent to 16.97 per cent.

Greater diversity among the people working on AI applications, whose subconscious biases may affect data selection and design choices, can also make a difference, experts say.

A lack of women in tech is an industry-wide problem. Alibaba founder Jack Ma said in a speech last year that only 13 per cent of technical roles in the company were filled by women, while Baidu’s recent report stated that 33 per cent of its technical staff were women as of last year.

Chinese women in AI still face barriers to equality, top female scientists say

When most people working in AI are men, it is inevitable for biases to make their way into algorithms, said Dong. “I think people might not do these kinds of things deliberately, but there will be some hidden bias.”

“AI is a technology that serves human beings. Up until the day when equality becomes the reality in human society, the technology will still be influenced [by real-world biases],” said Huang Xuanjing, a professor at the School of Computer Science at Fudan University, who added that there are policies in China to encourage women to join the field, including dedicated research grants and financial aid.

People care more about the performance of the algorithm and whether it can fix practical problems. If you are still hungry, you won’t care if you eat well or not.

But Dong said that while the “overall environment [in China] is good”, social stereotypes, such as those that say men are more suitable for a career in tech, might prevent more women from joining the industry.

Society can only achieve fair AI outcomes if it works as a whole, not just with the effort of a few individuals, and many people have yet to realise that the technology can harbour biases, the associate professor said.

“People [currently] care more about the performance of the algorithm and whether it can fix practical problems. If you are still hungry, you won’t care if you eat well or not,” she said.

“But if we only pay attention to the problem after it has developed to a certain level, it will be too late.”