Kuaishou IPO: live-streaming e-commerce holds promise for future profitability but remains clouded by regulatory uncertainty

- Kuaishou’s live-streaming e-commerce business has set itself apart with celebrities and devoted fans willing to buy whatever they are selling

- The business is helping make Kuaishou Hong Kong’s hottest IPO ever, but complaints about product quality have some concerned about future regulation

One selling point for Kuaishou, the Chinese video-sharing app that has turned into Hong Kong’s hottest initial public offering ever, is its eye-popping growth in “live-streaming e-commerce”, a newly popular form of shopping online in China.

But analysts have said the business model is at risk of increased regulation from Beijing, which could lead to slower growth and make it harder for Kuaishou and similar platforms to profit from the booming service, which often features online personalities or celebrities showcasing products in live broadcasts to woo viewers into placing orders.

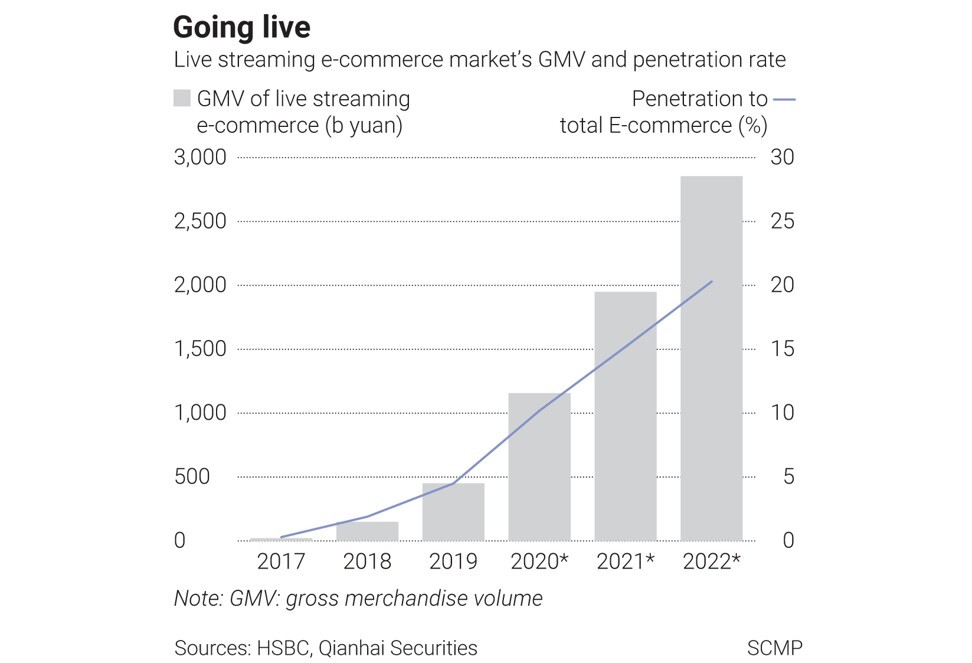

In 2020, KPMG estimated China’s live-streaming e-commerce industry was worth about 1 trillion yuan (US$154.6 billion) – a value primarily shared among three players. Taobao Live – from China’s largest e-commerce platform owned by Alibaba Group Holding, the owner of the South China Morning Post – still accounts for about half of the market, according to Qianzhan Industry Research Institute. Kuaishou and its rival Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, share the bulk of the other half.

Kuaishou has stood out from the crowd owing to the platform’s “fan culture”, which has made it ideal for growing live-streaming e-commerce. Its gross merchandise value (GMV) from the business has ballooned to 204 billion yuan in the first nine months of 2020, surging from the 59.6 billion yuan it made in all of 2019, according to the company’s prospectus published with the Hong Kong stock exchange.

Analysts see Kuaishou’s ability to sell goods to fans through celebrities as a strength in its road to future profitability. The company lost 9.4 billion yuan in the first 11 months of 2020 despite revenue of 52.5 billion yuan, according to the prospectus. Revenue from “other services”, the section of the prospectus that includes live-streaming e-commerce, reached 2 billion yuan in the first nine months of 2020, or 1 per cent of Kuaishou’s total GMV.

Will Chinese video app in massive Hong Kong IPO be a good investment?

China’s consumer complaint centre received 21,900 complaints about live streaming in the first nine months of 2020, a rise of 500 per cent from a year earlier. Of those, 60 per cent were specifically related to live-streaming e-commerce, according to the State Administration of Market Regulation (SAMR).

In November, SAMR issued regulatory guidelines on sales through live-streaming which specify legal responsibilities for online platforms, product suppliers and live-streamers. One requirement is for companies to verify the authenticity of the information provided by product suppliers and live-streamers. Other government regulators have also vowed to enhance supervision.

“There will be intensified regulation on live-streaming e-commerce this year,” said Ding Mengdan, a lawyer at Yingke Law Firm in Hangzhou. “The wild expansion of the past will no longer be possible.”

Over the last two years, regulators have largely remained hands-off regarding live-streaming e-commerce amid rapid growth of the business model.

Live-streaming shopping a new black spot in e-commerce

Technically, many existing laws in China could be applied to the business, including laws on e-commerce, consumer rights protections, unfair competition, product quality and advertising. But the power to enforce each of these laws is scattered across different agencies, which include the Office of the Cyberspace Administration and the Ministry of Culture, lawyers said.

Regulators in China usually do not take action until “something has happened”, making regulations in the country largely reactive, said Huang Wei, a partner at Yingke.

The risks of buying through live-streaming became apparent in December after a scandal involving one of the biggest idols on Kuaishou. Xinba, who had 70 million fans on the platform and sold 1.25 billion yuan worth of products in a single session last summer, was found to have been selling fake bird’s nest – an expensive Chinese delicacy.

After the live-streaming session, Xinba’s firm was fined by the local market regulator in Guangzhou for 900,000 yuan. Kuaishou also blocked the celebrity, who accounted for a fifth of the platform’s GMV in 2019, for 60 days.

Kuaishou did not respond to a request for comment.

Wang Sixin, a professor at the Communication University of China in Beijing, suggested China could soon find ways of holding all sides accountable for such incidents, including online celebrities, product suppliers and platforms.

“If they have signed contracts and have a stable business relationship, they share joint and several liability,” Wang said. “That means when something goes wrong, the live-streamer and his team, brands, and in some cases even the platforms, should take responsibility. No one can escape from the rope.”

One weakness of the business model, according to insiders, is that it gives a big share of the revenue to celebrities like Xinba, squeezing profit margins for manufacturers, sometimes leading them to lower product quality to cut costs.

Top live-streaming influencers can be very expensive, often charging rates above those of A-list movie stars, according to industry insiders who spoke with the Post. A top influencer could charge a booking fee of 90,000 yuan to 250,000 yuan for a promotion lasting three to 10 minutes. Some influencers ask for a commission fee on top of those charges, which could be as high as 30 per cent of the sales revenue for the product.

How new millennial billionaires built the biggest rival to China’s TikTok

Influencers also want to make sure the products are as cheap as possible to stay competitive on their platforms, so they press suppliers to cut prices, the insiders said.

The brands agree to the terms because they want to increase awareness and drive new sales, according to Ryan Molloy, CEO of Shanghai-based RedFern Digital, an agency that helps connect brands and influencers. This is despite the fact that it is difficult to turn a profit under these conditions, “because you already have a 20 per cent commission, and then you probably got to do like a 50 per cent discount”, he said.

Since the Xinba scandal, Kuaishou has already started to take action.

A merchant who sells goods on Kuaishou using influencers, who asked to be identified only by her surname Qin, said the platform recently asked her to send in products for a quality check.

Luo Qiong, the vice-president of Kuaishou’s e-commerce department, said during an interview in December with China Market Regulation News that the platform has been strengthening quality controls. This includes a 10-member team that buys products from randomly selected live streams and sends them to third-party institutions to check the quality.

“[The live-streaming industry] has become more rational now. In the past, a single live-streaming show could easily attract tens of thousands of orders,” Qin said. “Now, consumers may think again … as the business becomes standardised and exaggerated promotions are prohibited.”