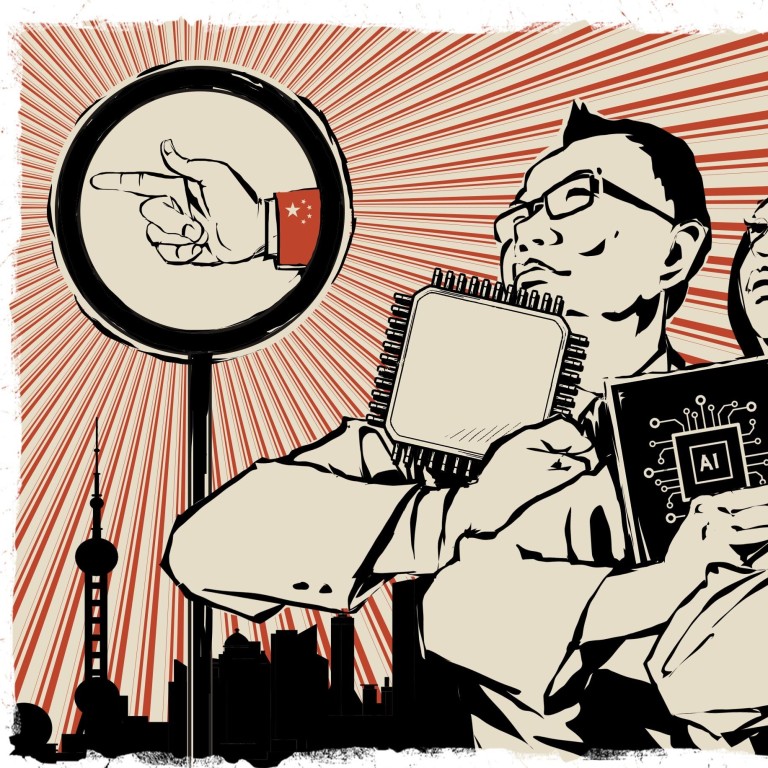

Big Tech set for starring role at Beijing’s ‘two sessions’ political gala amid regulatory heat and US tech war

- The tighter regulatory environment from Beijing has fanned speculation over whether Big Tech’s best days are over, after decades of rapid growth with less oversight than traditional industries

- Analysts are divided on whether being linked to the Communist Party will affect the global ambitions of Chinese tech companies amid ongoing US-China tensions

Tech entrepreneurs at China’s biggest annual political gala next week will be under pressure on two fronts as Beijing pushes its national strategy of technology independence while ratcheting up regulatory scrutiny of their business operations.

This year’s meetings, informally known as the “two sessions”, carry even greater importance because they not only kick off the nation’s latest five-year plan, but commemorate the centenary of the Chinese Communist Party too. The event will also be the first gathering of the country’s tech elite since China’s antitrust regulators began to investigate technology conglomerates for their market behaviour last November. The spate of investigations, including financial penalties and reprimands, have put everyone on notice.

The tighter regulatory environment from Beijing has fanned speculation over whether Big Tech’s best days are over, after decades of being able to rapidly grow their businesses with less oversight than traditional industries.

“Tech representatives will likely put their heads down and toe the [Communist] Party line at this year’s gathering ,” said Xiaomeng Lu, a senior analyst at Eurasia Group. “Chinese entrepreneurs will focus on showing support to the government’s agenda and put their loyalty to the party on display”

Antitrust guidelines put the onus on regulators to prove Big Tech monopolies

When contacted by the Post for comment about their 2021 proposals, Tencent, Xiaomi and Baidu replied that they had not yet released them.

The degree of political influence wielded by two sessions’ delegates is open to debate given the ceremonial nature of the events, but the inclusion of tech leaders like Ma, Li and Lei in recent years has shown that Beijing recognises the role of private tech firms in China’s development.

The tech delegates are required to submit policy proposals to show their social responsibility. The delegates also include Qihoo 360 head Zhou Hongyi, NetEase chairman William Ding Lei, Sogou CEO Wang Xiaochuan, and Sequoia Capital founder Neil Shen, one of China’s most successful venture capitalists.

Lu said tech leaders are likely to voice their commitment to semiconductors, artificial intelligence (AI) and quantum computing as these are key areas identified by Beijing in its 14th five-year plan. Away from the limelight, they could come under pressure to be more proactive in showing allegiance to state policies while shunning potential controversy, according to analysts.

That task has become harder amid the ongoing US-China tech war. Attendance at Beijing’s top political event could be seen by foreign governments as a sign of blurred lines between the Chinese state and private sector, a fact that could hinder their global expansion plans at a time when suspicion over Beijing’s influence remains high from Washington to Brussels.

Eurasia Group’s Lu said the Biden administration might view the two sessions as evidence of further integration between the government and private companies in China. “It will be more challenging to portray themselves as truly independent global players in front of an international audience if Chinese tech leaders are viewed as an extension of the Chinese government,” Lu said.

When Xiaomi’s Lei was asked by a BBC reporter in 2018 about the decision to abolish the two-term limit to allow Chinese president Xi Jinping to serve indefinitely, he just replied “sorry, sorry”. Xiaomi was recently slapped with a US investment ban for having alleged ties to the Chinese military, a charge it denies.

One challenge facing tech sector representation in the two sessions, which elects new delegates every five years, is that it does not fully represent China’s rapidly changing technology landscape. None of the young generation of Chinese tech CEOs, such as ByteDance’s Zhang Yiming, Meituan’s Wang Xing, Pinduoduo’s Colin Huang and Kuaishou’s Su Hua, are members.

Other notable tech exclusions are Huawei Technologies Co founder and CEO Ren Zhengfei, who has long maintained good relations with the central government, and Alibaba Group Holding founder Jack Ma, who once told his employees to “be in love with the government, but not married to it”. (Alibaba owns the Post.)

While Huawei has battled for two years to survive tough US trade restrictions, similar challenges loom for Qihoo 360, which in June last year was added to the US Commerce Department Entity List that restricted access to US products and services. For its part, Xiaomi has gone to US court to challenge Washington’s ban on US investors buying its shares, while the Trump administration’s US ban on Tencent’s ubiquitous social media app WeChat has been put on hold by the Biden administration.

Why semiconductors are important in the US-China tech war

Even though Alibaba’s Ma has never been an NPC or CPPCC member, the last-minute decision by authorities last November to stop the initial public offering of Alibaba affiliate Ant Group looks set to cast a long shadow over tech representatives at this year’s two sessions.

Delegates “should have all learned a lesson from Jack Ma” openly challenging state regulation, said Sun Xin, senior lecturer in Chinese and East Asian Business at King’s College London. China’s tech CEOs are unlikely to raise any concerns about tighter regulatory scrutiny – at least not in public – as they know that the two sessions is not a venue to voice complaints.

“Some will even show greater support for the top policy agenda of the party,” Sun said.

Ma fell out of favour when he questioned China’s financial regulations in a public speech in Shanghai at the end of October ahead of Ant Group’s scheduled dual listing in Shanghai and Hong Kong. The share offering was called off at the last minute after regulators intervened.

Authorities subsequently rolled out new rules aimed at bringing the fintech sector into line, following that up with a broader antitrust crack down on monopolistic practices by Chinese tech giants. Beijing’s antitrust watchdog launched an official antitrust probe into Alibaba on Christmas Eve.

After his Shanghai speech, Ma remained out of public sight for nearly three months until an appearance via video in January where he said Chinese entrepreneurs must serve the country’s vision of “rural revitalisation and common prosperity”.

Sun said membership of the CPPCC or NPC affords tech bosses a unique venue to socialise with top policymakers, bureaucrats and other elites, providing unofficial opportunities for them to lobby for decisions in their favour.

For example, the delegate proposals from tech bosses are often directly related to their business interests and are often in line with the latest government announcements for new development programs. Last year, Tencent’s Ma suggested speeding up the formulation of a national industrial internet strategy – a goal that aligned with the company’s own strategy. He also proposed the development of “smart hospitals” – another Tencent business focus – to help ease the burden for medical workers during a public health crisis like Covid-19.

Baidu’s Li, whose company began investing in AI several years ago, has repeatedly advocated for AI programs at the two sessions, and he suggested last year that China ramp up efforts to build world-leading infrastructure for AI and smart transport. Baidu is a leader in China’s autonomous driving sector.

In April last year, China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) included AI and industrial internet in a list of new infrastructure to be developed.

Xiaomi’s Lei, a space enthusiast who has invested in Beijing-based commercial space firm Galaxy Space, last year proposed the development of satellite internet that could deliver online access to places not covered by land-based networks, such as remote and poorer areas, as well as on ships and planes. His proposal came after China added satellite internet to a list of new infrastructure industries that would receive greater government support.

Li Yi, chief research fellow at the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, said that although delegates are elected and step onto the stage of the country’s biggest political event, they have limited power when it comes to the actual policy and law making process.

Sun agreed, saying that tech entrepreneurs, like most NPC deputies and CPPCC members, have “little independent policy influence”, and that their individual submissions are just seen as one voice and not a force for change.

“The lawmaking process is ultimately dominated by the state,” Sun said. “If there were historical instances in which CEO proposals became real policies, it is more likely the case that relevant government bodies had already conceived such policies themselves.”

At the end of the day, analysts say membership of Beijing’s political gathering offers more advantages than disadvantages, even when factoring in possible scrutiny from abroad. While it remains to be seen how the Biden administration will interpret the political links between private Chinese firms and the Communist Party, Sun said no major company in China can afford to defy the demands of Beijing.

In the end, membership of the two sessions may not prove a major impediment to the global ambitions of Chinese tech entrepreneurs because the source of Sino-US tensions are more ideological, according to Li.

“The US won’t allow anyone to challenge its hegemony, and the ideological conflicts between the US and China won’t change with a new administration,” Li said.