Tencent’s China Literature wants to woo 100,000 American and Canadian writers

- China Literature, the country’s biggest web novel publisher, plans to boost its North American business with English works

- Online fiction has proven to be a profitable business in China

China Literature, a subsidiary of tech giant Tencent Holdings, has been churning out profits from one of Chinese netizens’ favourite pastimes: reading serialised novels. Now it is trying to export that proven business model to the rest of the world, with plans to double the number of its North American writers in 2021, the company’s head of international business Sandra Chen told the South China Morning Post.

“We aim to grow the number of North American writers to 100,000 this year,” said Chen, who leads Webnovel, the overseas business unit of China Literature and the name of its English-language website.

Webnovel’s renewed push comes as the number of overseas readers of Chinese web fiction is forecast to grow from 32 million in 2019 to 49 million this year, according to business consultancy iResearch.

While China Literature and IReader Technology – the country’s second largest e-publisher backed by search engine giant Baidu and TikTok owner ByteDance – are both active in translating Chinese web novels into foreign languages, Webnovel is now betting on English works written by native authors to reach more international readers.

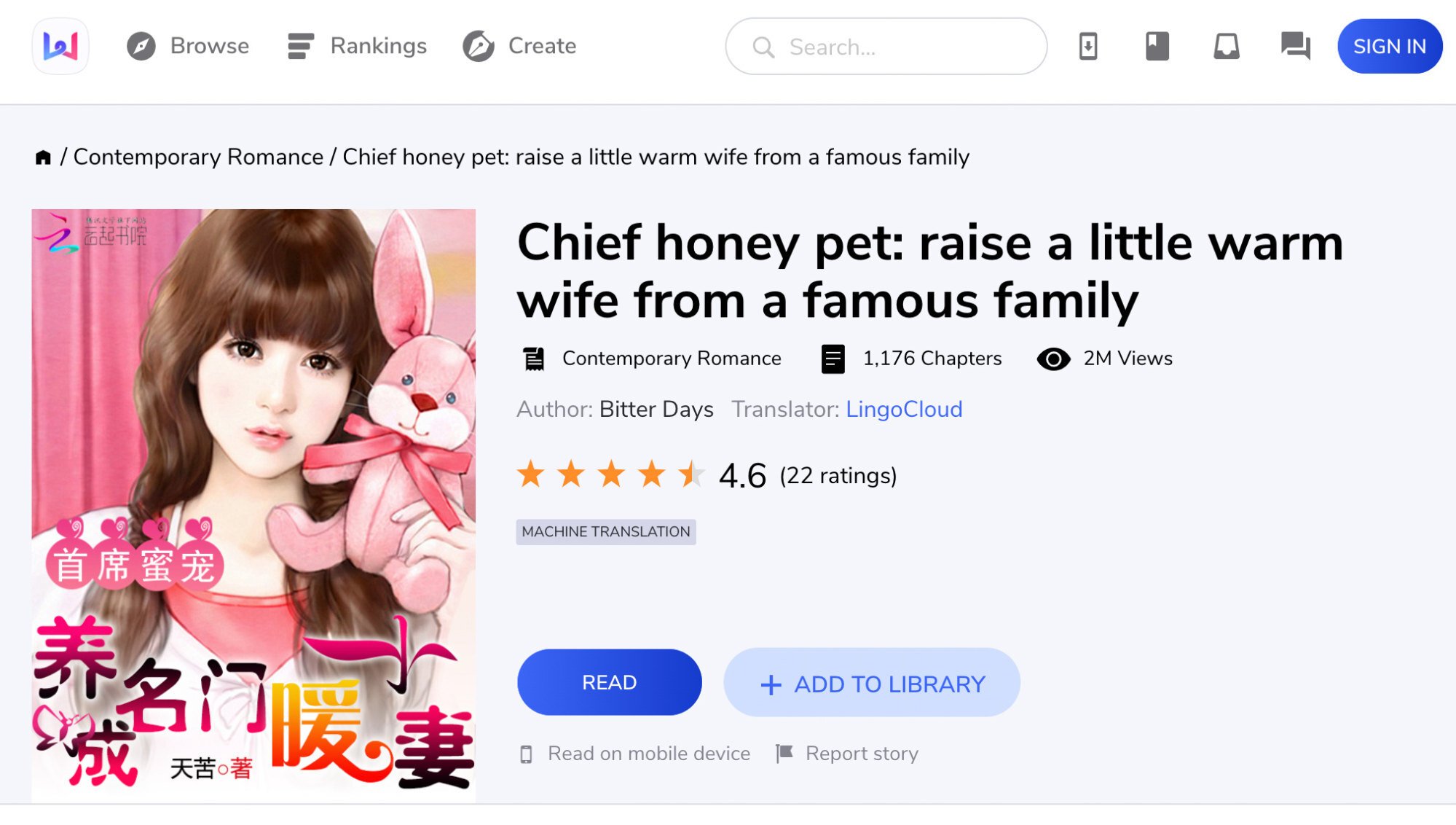

Launched in 2017, Webnovel currently has around 100,000 writers – a tiny fraction of the 9 million registered on China Literature’s bevy of platforms. Fewer than half of Webnovel’s authors come from North America, Chen said.

Last year, the platform hosted 200,000 novels, according to financial results posted by the Hong Kong-listed China Literature last week. In comparison, China Literature had 13.9 million literary works across all its platforms.

By boosting the number of North American authors, Webnovel hopes to crack a key market that has shown a strong demand for literature and a willingness to pay for content, Chen said. The priority is to develop a “big enough pool of good content”.

“We hope to attract not only amateur writers, but also traditional writers, including screenwriters, to join [Webnovel],” she said.

Can AI help China’s web novels find more English readers?

Just like their Chinese counterparts, authors registered with Webnovel earn money from royalties, as well as revenue share from clicks and tips from readers. The more popular their works are, the more money they receive.

To entice more talented writers to join Webnovel, the platform promises a minimum copyright income and weekly writing workshops, Chen said. It also takes care of promotions.

The best writers get additional benefits. My Vampire System, a fantasy story by British author Jack Sherwin writing under the nom de plume JKSManga, is one of the hottest novels on the platform, boasting 24 million reads. Last year, it won the top prize at Webnovel’s Spirity Awards, taking home US$10,000.

While Chen declined to name the top earners, she said some writers can make over US$10,000 a month.

Webnovel also hopes that North American writers will be attracted by China Literature’s record of turning some of its most successful works into television shows.

The Rise of Phoenixes, a drama series that launched globally on Netflix in 2018 in more than a dozen languages, was adapted from the Chinese web novel Huang Quan, first published on China Literature’s female-focused platform Xiaoxiang Shuyuan.

The company’s efforts to penetrate the American market, however, come as tensions are flaring between China and the US.

Chen declined to comment on the impact of the geopolitical tensions on China Literature’s business.

At the time, China Literature denied most of the accusations, although it admitted that it “made mistakes and detoured”. It also rearranged its agreements with some writers to settle the dispute.