Advertisement

US-China tech war: Huawei is still on the hook as Joe Biden fine-tunes America’s competitive strategy with Beijing

- The US Innovation and Competition Act earmarked US$54.2 billion towards shoring up America’s competence on a number of technological fronts, including chips production, and catch up on 5G technology

- It also leaves Huawei on a list of restricted entities, banning it from gaining access to US hardware and software until it can prove that it no longer poses any threat to US national security

Reading Time:7 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

68

In the second of a five-part series on US-China technology policies under the Biden administration, Pan Che, Xue Yujie and Celia Chen take a look at how Huawei Technologies – the very first to come into the policy cross hairs of the former Trump administration – has fared nearly six months under the new regime, and what this says about the future of US-China relations over technology. The first part is here.

A crucial piece of legislation wound its way this week through the United States Senate, dashing any hope that the new administration of Joe Biden would offer a friendlier stance than his predecessor towards China, particularly over technology.

The US Innovation and Competition Act earmarked US$54.2 billion towards shoring up America’s competence on a number of technological fronts, including semiconductor production, and catch up on 5G telecommunications technology. More crucially, it leaves Huawei Technologies – the world’s largest 5G equipment maker and the first victim of the US-China tech war – on a list of restricted entities, banning it from gaining access to US hardware and software until it can prove that it no longer poses any threat to US national security.

Advertisement

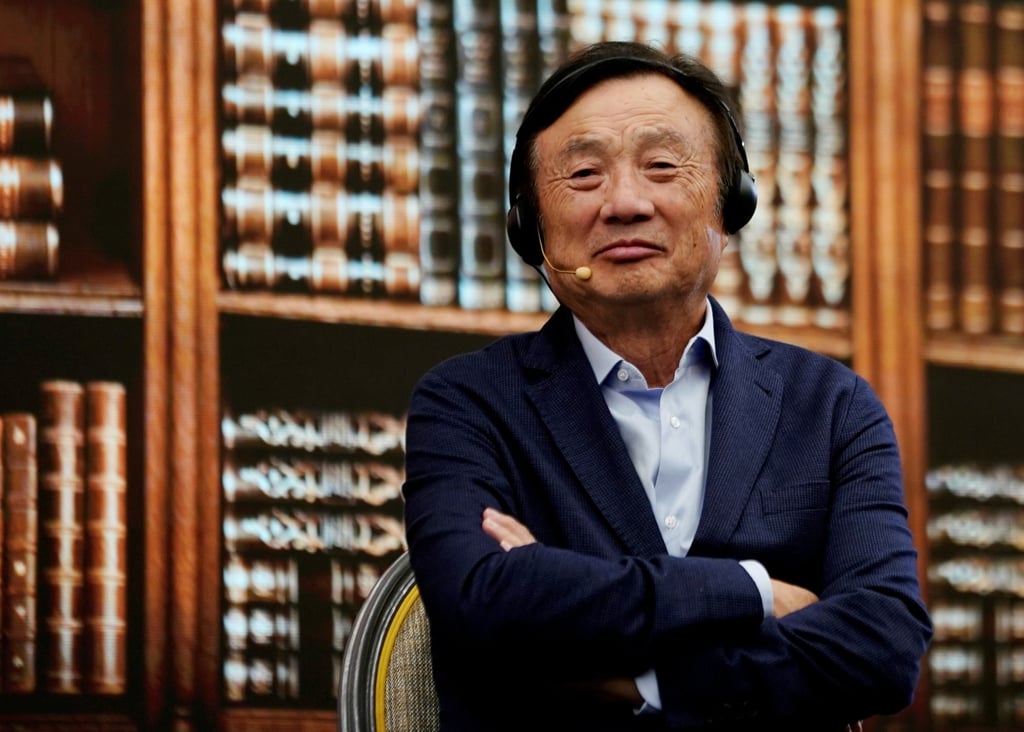

The bill, which awaits passage in the House of Representatives before Biden signs it into law, dispels any illusion that the 46th American president would unwind the policies of his more hawkish predecessor. It’s a reality that has not been lost on Huawei’s septuagenarian founder Ren Zhengfei, whose eldest daughter Meng Wanzhou has been awaiting extradition in Vancouver to face trial in the US since 2018.

It would be “extremely difficult to remove Huawei from the entity list,” Ren acknowledged during a rare visit in February to the Shanxi provincial capital of Taiyuan, the hub of China’s coal-mining industry, adding candidly that the country’s technology champion was in a fight for its very “survival.” Huawei, a closely held company that has been reporting its financial results since 2000, posted its weakest annual revenue growth in a decade last year.

The company, which began as an importer and producer of private phone exchanges in the 1980s in southern China’s technopolis of Shenzhen, has had to branch out into recreating its own hardware and software ecosystem to replace the technology that it can not buy from Qualcomm and US software vendors. That includes earmarking billions of dollars of research funding towards its HiSilicon unit to make semiconductor chips, and even writing its own operating system (OS) called the HarmonyOS to break the American duopoly of iOS and Android for smartphones.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x