Analysis | China antitrust: Didi’s ride hailing dominance prompts scrutiny before it sets forth for its Uber-beating New York IPO

- Didi-Chuxing is putting the finishing touches of its plan to raise up to US$10 billion in New York, in an initial public offering that would value the nine-year-old company at US$100 billion, bigger than Uber

- Didi, with 493 million annual active users globally and 13 million active drivers in China, commands 90 per cent of a ride-hailing market estimated at US$3.9 trillion by 2040

In the third instalment of a four-part series on China’s antitrust crackdown on technology companies, Masha Borak looks at the ride-hailing industry and its dominant operator Didi-Chuxing. The first instalment on streaming music is here and the second instalment on games is here.

“Didi will not comment on the unsubstantiated speculation from Reuters’ unnamed sources,” said the company.

“Didi is now under close scrutiny by a whole host of regulatory authorities,” said Angela Zhang, director of the Centre for Chinese Law at the University of Hong Kong. “If Didi fails to adapt to the demands from these regulators, I believe there will be further escalation of regulatory actions.”

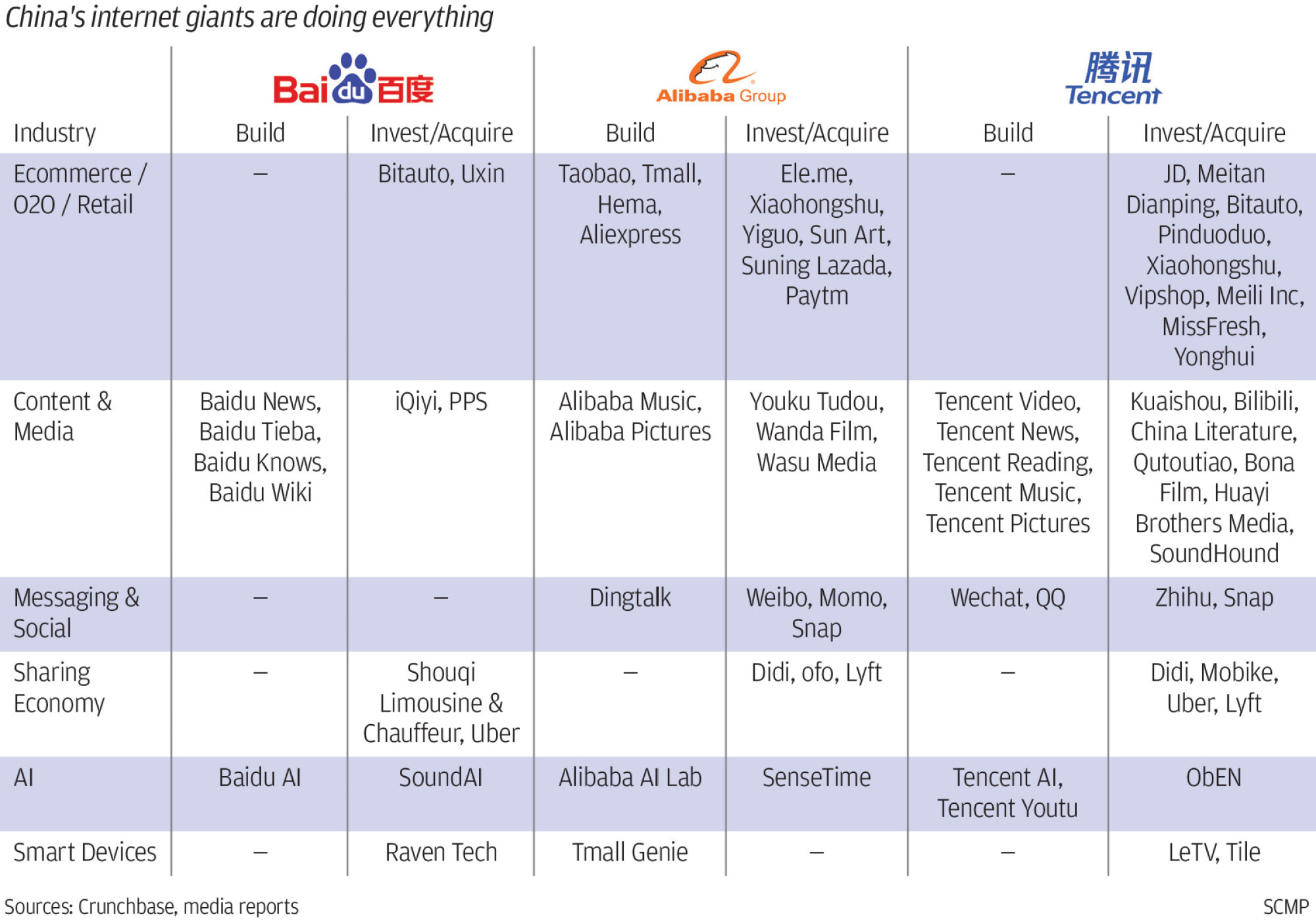

Didi is not the only Chinese technology behemoth to have come under the scrutiny of SAMR, as regulators catch up after more than a decade of laissez faire growth in every aspect of the country’s technology-related industry, from games to online entertainment, e-commerce to electronic payments.

The additional scrutiny on Didi is a sea change from a decade ago, when taxi fleets – mostly operated by state-owned companies -ruled the roads in China.

In June 2012, Alibaba’s sales executive Cheng Wei founded a company called Didi Dache, which allowed customers to hail for taxis through smartphone-enabled applications. Drivers could monitor calls for service, while the locations of drivers and passengers would be displayed in real time on the app’s built-in maps. Cheng persuaded Tencent to become an early backer.

The service was a hit, providing an instant salve for hailing rides for regular commuters and out-of-town travellers alike. The service broke the dominance of licensed taxi drivers, giving almost anybody with a smartphone and a vehicle the ability to earn a livelihood. Combined with China’s rapidly expanding electronic payment services Alipay and WeChat Pay amid the world’s largest smartphone market, mobile ride hailing was soon taking market share away from traditional taxi fleets.

“Ride hailing companies, and to a lesser extent on-demand online food delivery companies, have been massive disrupters, and naturally this has ruffled the feathers of incumbents in their industry who have lobbied to restrict the expansion of the new companies,” said Paul Haswell, a partner who advises tech companies at legal firm Pinsent Masons.

By 2015, Didi would command more than half of China’s ride hailing market. In February of that year, Tencent-backed Didi Dache merged with Alibaba-backed rival Kuaidi Dache to form Didi-Kuaidi, in which both technology behemoths became co-investors. The merged company raised millions of dollars from its investors to fund its cash-burn to subsidise the fares for passengers, and supplement the income of drivers.

After the takeover of Uber China, which has faced its own share of controversies in the US and other markets, Didi was swamped with public criticism and lawsuits. Some, including local taxi alliances, accused it of abusing its market power while others denounced it for disregarding safety following a high-profile passenger rape and murder case in 2018. The rights of gig workers have also been a common complaint.

But unlike its Southeast Asian counterpart Grab, which was fined $13 million (US$9.5 million) by Singaporean competition watchdogs in 2018 after its merger with Uber, Didi has so far avoided tougher penalties.

Regulators have been reluctant to break up Didi after the merger with Uber because mergers are very costly to unwind, said Zhang, who has analysed China’s legal framework in her book Chinese Antitrust Exceptionalism. There has also “not been direct evidence of consumer harm resulting from the merger transaction,” she said.

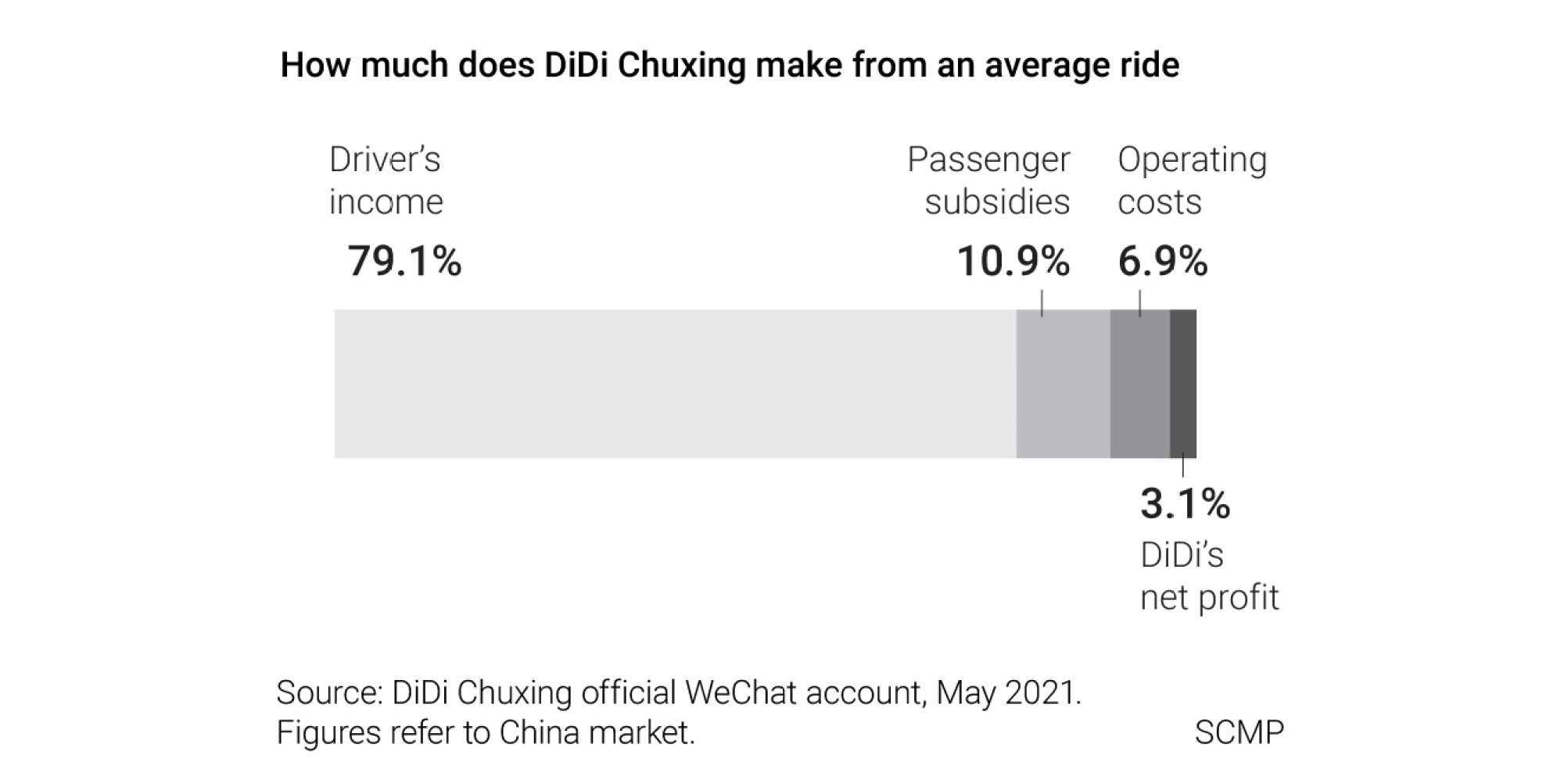

Allegations of unfair pricing, unreasonable fees and forcing out smaller rivals – some of the antitrust benchmarks for punitive action – have continued to dog the company, served in China by 13 million drivers. The ruling Communist Party, poised to mark its centenary this year, is particularly anxious to tamp down any social grievance with the potential of ballooning into hot button political issues.

In this light, the regulators are concerned about claims that Didi is abusing its dominance to exploit drivers, said analysts including Zhang.

While showering users and drivers with subsidies have contributed to this, Didi explains its lack of profit by the nature of the ride-hailing business. Thanks to the rules of the gig economy, the supply of drivers can be fickle, fluctuating from hour to hour and day to day, making the platforms reluctant to increase their commissions.

Ride-hailing companies also cannot increase prices for users significantly if their customers can just as easily take a bus home instead of hailing a car.

Regulators in the past were less focused on the sector as Beijing stimulated the growth of internet giants as part of its economic upgrade and officials peppered their speeches with buzzwords such as “sharing economy”.

“The focus then was on growing internet businesses,” said Ma Rui, a venture capital investor and host of the podcast Tech Buzz China. “Chinese regulators, in general, are about doing the right thing at the right time not having one inflexible set of rules that don’t change.”

“There was a feeling that the previous framework was inadequate or not clear enough to tackle the issues,” said Marc Waha, an antitrust consultant at Norton Rose Fulbright law firm.

The company, which now operates in 14 markets worldwide, has been aware of its position under the magnifying glass warning investors in its IPO filing that anti-monopoly regulatory actions could put a damper on their business.

Ride hailing companies have been keeping governments happy by “treading a tightrope which can change at any time,” said Haswell. Compared to the likes of Tencent and Alibaba, Didi does not have quite so much influence in all aspects of everyday life in China which may make it a smaller target for regulators.

But governments across the world have been reining in on technology companies, ranging from Facebook and Google to Tencent and Alibaba.

“There seems to be a global push to investigate the considerable power wielded by tech companies so we should assume no organisation is immune from scrutiny,” said Haswell.

The legal issues that ride hailing companies such as Didi will face are similar to many other digital platforms including the Amazons, Alibabas and the Rakutens of this world, Waha said.

While companies such as Grab, Uber or Didi may have started out their voyage with ride hailing, they have branched out into insurance coverage and financing for drivers and providing services for their users such as food delivery. Didi has also branched out into areas such as smart cities and self-driving cars.

“The business model is very much one of building super apps,” said Waha.