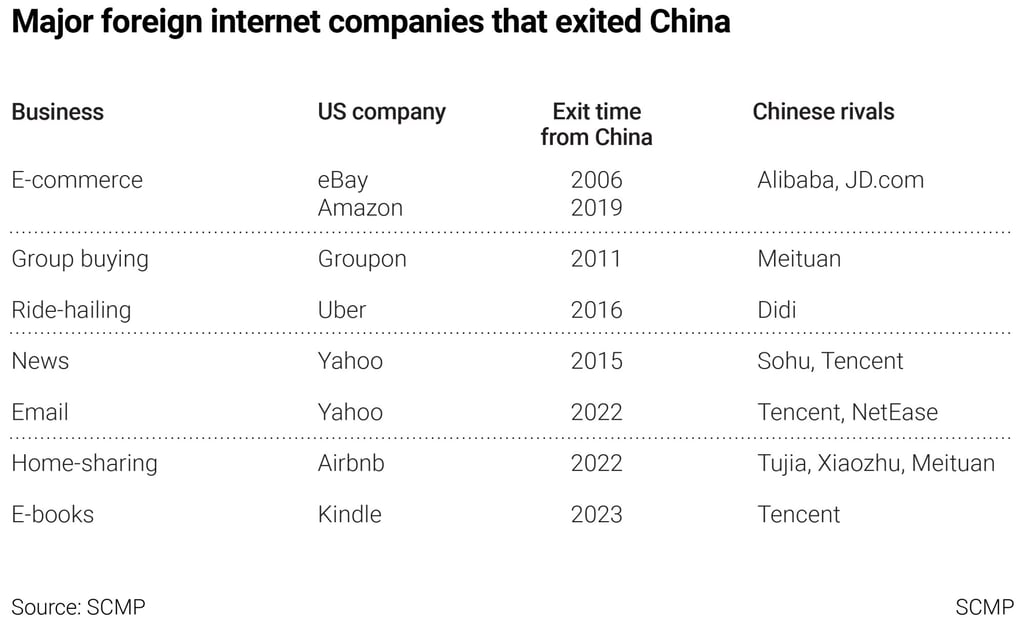

China’s hostile environment for Western tech pushed out Amazon and Airbnb, but competition remains the biggest challenge

- An increasing number of Western internet firms are calling it quits in the world’s second largest economy, citing Covid-19 and a tougher regulatory environment

- More recent challenges just tell part of the story, according to analysts, who say platforms like Airbnb, Amazon and Uber were outcompeted by local rivals

Just by the size of its economy and population, China has long stood as a market that global businesses cannot afford to ignore. Yet a string of recent exits, including Airbnb and Amazon, shows the country is increasingly becoming a cautionary tale for multinational firms.

While economic reforms started almost half a century ago, a recently emergent middle class has made China even more appealing to many global firms seeking a toehold in the world’s second largest economy. Not even one of the strictest censorship regimes in the world has been enough to deter internet giants. Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook owner Meta, was still courting favour with Chinese officials as recently as 2016, when he went for a highly publicised jog in Beijing through air thick with smog.

While Zuckerberg never succeeded in launching his social media services in China, many other internet giants have tried their hand at the market only to flee years later – and the number of retreats are rising. A combination of an increasingly intrusive regulatory regime, fierce competition from local rivals, and shifting Chinese consumer preferences has pushed many firms to throw in the towel.

“China’s severe lockdown and Covid restrictions are just some of the contributing factors to Airbnb’s exit, but they hardly constitute the main reason,” said Angela Zhang, an associate professor of law at the University of Hong Kong. “The fundamental reason has to do with the stiff competition that Airbnb faced in the Chinese internet market from indigenous rivals such as Meituan and Ctrip.”