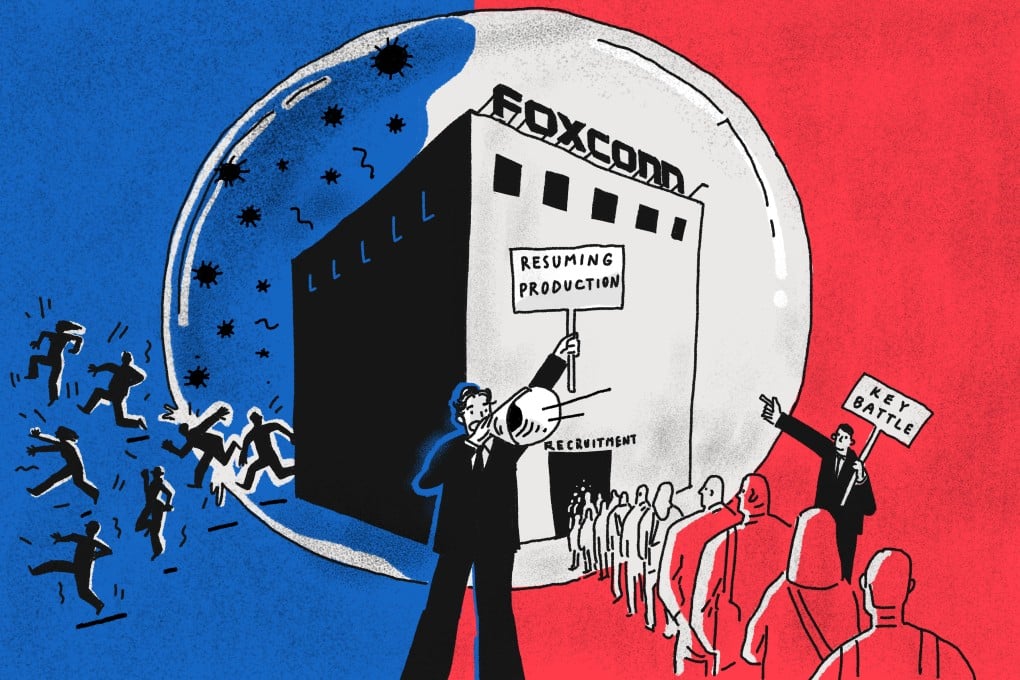

Inside Foxconn’s ‘iPhone City’: how Apple’s biggest contractor fell victim to China’s zero-Covid policy

- The vast Foxconn compound in Zhengzhou – known as ‘iPhone City’ – can accommodate up to 300,000 workers who live on-site in dormitories

- This human link in Apple’s iPhone supply chain has broken down as a direct result of China’s strict ‘dynamic zero’ Covid-19 policy

In a widely cited anecdote about the power of the Chinese workforce, a manager at an iPhone factory was once able to rally 8,000 workers from their dormitories to do a 12-hour shift at short notice, with nothing more than an offer of a cup of tea and some biscuits. Apple urgently required a refit on a new iPhone model, and within a week production was back on track.

The unrivalled discipline, efficiency and reliability of Chinese workers, as illustrated by the anecdote, convinced Apple – the largest US consumer electronics company – to outsource its iPhone assembly to China – and stick with that decision despite rising labour costs, human rights controversies and more recently intensified rivalry between Beijing and Washington.

Foxconn Technology Group’s factory in Zhengzhou, capital of central Henan province, was designed to take advantage of China’s highly organised labour force. The vast compound – known as “iPhone City” – can accommodate up to 300,000 workers who live in on-site dormitories in nearby residential high-rise buildings. This army of young workers – men and women in their 20s and 30s – have made China an integral part of Apple’s supply chain.

While most countries in the world, including those in Asia, have abandoned strict pandemic controls in favour of living with the virus, the Chinese government has doubled down with mass testing, snap lockdowns and strict quarantines.

The fear among the fleeing Foxconn workers was a reaction to years of Chinese state propaganda that tried to justify draconian pandemic controls by emphasising the health threat posed by the virus. Even after the milder Omicron variant became dominant, state propaganda had been pushing the line that Covid-19 was deadly and can cause permanent damage to health.

When Zhengzhou, a city of 10 million, began to report confirmed cases in the first week of October, the fear and panic eventually spread to the Foxconn compound, which was operating on a 24-hour shift to meet peak season demand after the new iPhone 14 series was unveiled in September. For workers, many of whom are migrants from other towns and smaller cities in Henan, peak season is the best time to maximise earnings by working overtime.