China counts on AI to find a cure for its ailing health care system

The world’s most populous country is embracing AI to fill resource gaps in its health system, as private firms team up with hospitals on experimental diagnosis services

With more than 2,000 different skin diseases, it is impossible for non-specialists to know about all of them. That was the problem facing Shi Jiang, who for two decades has worked as a general practitioner in a community health clinic in Shanghai, where most his patients are elderly.

“Sometimes they would show me their ageing spots or moles, worried if they were abnormal. But it has been a long time since my dermatology studies at college,” the 45-year-old Shi said.

When he heard last month about Quality Skin, an experimental app for AI-powered dermatology diagnosis, Shi jumped at the chance to be among the first group of doctors to try it.

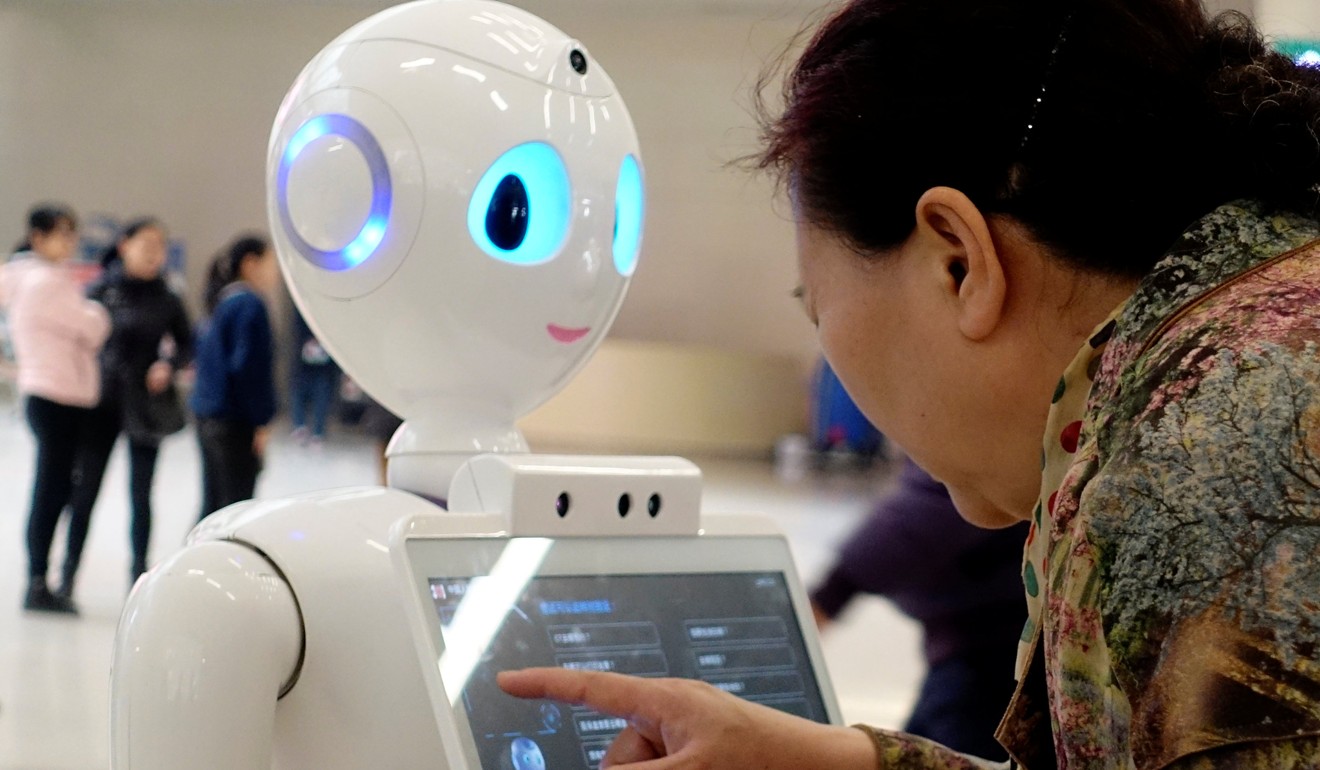

In China, health care has become one of the latest applications for AI, along with security and new retail, where technologies like natural language processing and computer vision are being applied to greatly improve efficiency in a country with an acute shortage of qualified doctors and nurses. Chinese companies from start-ups to tech giants are seizing the opportunity to apply AI solutions to everything from machine reading of CAT scans to processing and analysing medical queries.

Dermatology will be among the first disciplines to embrace AI, according to Cui Yong, research chief at China-Japan Friendship Hospital, which was hand-picked by authorities to experiment with internet-based medical consultations and came up with the Quality Skin app that can produce probability-weighted results within a minute of receiving high-resolution images of the skin condition.

“There are over 2,000 kinds of skin diseases, while fresh graduates can only recognise 100 and even the most experienced doctors would only encounter 800 in their entire career,” he said. “Most doctors would avoid giving an opinion on a disease they are not familiar with, so as many as 60 per cent of the cases are under risk of misdiagnosis.”

While only 7.7 per cent of China’s hospitals are rated “triple-A”, they handled half of all outpatient visits in 2016, according to industry estimates cited in Ping An Doctor’s recent prospectus. Most doctors only receive training at the start of their careers and don’t have the opportunity to keep up with any new medical developments.

In China, dermatology departments at hospitals and clinics account for about 3 per cent of the 240 million total patients visits per year.

“China is already far ahead of the US in AI enabled diagnosis,” said Ni Hao, health care chief executive at Yitu Technology, a Shanghai-based AI start-up that specialises in facial recognition systems. There are two reasons for that, according to Ni. First, the shortage of doctors in the US is not as dire as in China, and second, US AI-start ups may not be able to afford a large medical team because American doctors earn between US$250,000 and US$300,000 per year.

Yitu touts a team of about 400 doctors, most of whom work part-time for about 10 hours a week to help label data, while one fifth of its full-time employees have a medical background.

In its move into health care, the company has partnered with West China Hospital in Chengdu on an AI-driven lung cancer diagnosis system that can tap into about 280,000 real world lung cancer cases – the world’s biggest database of its kind – and provide a diagnosis within seconds.

Yitu is one of dozens of Chinese AI start-ups that have emerged in recent years, with many now focusing on health care. In November, an intelligent robot developed by Shenzhen-listed iFlytek passed the country’s written national qualification exam for doctors.

The AI health care opportunity has not been overlooked by the country’s biggest tech giants.

Tencent Holdings, operator of the ubiquitous WeChat messaging platform, was hand-picked by Beijing last November to spearhead AI applications in health care. It has since teamed up with over 100 triple-A rated hospitals across the country.

Last week, Shenzhen-based Tencent launched its first open platform for AI medical diagnostics. Using computer vision and AI analysis, the so-called Tencent Shadow Chaser covers 700 diseases which make up 90 per cent of the most common outpatient cases.

Similar to how human doctors are trained, the platform has gone through three stages of “training”. First was natural language processing and deep learning of medical textbooks, health records and diagnostic directories to produce a store of medical knowledge, followed by development of diagnostic algorithms and optimisation of the algorithms with the help of human medical specialists, according to the company.

Shadow Chaser, which has been included in about 10 million health knowledge databases, is a step towards building the next generation of smart health services, Tencent vice-president Chen Guangyu said in a statement.

Last week, China’s leading search engine Baidu moved to open source AI technologies that can help pathologists detect breast cancer, while Alibaba Group Holding, China’s biggest e-commerce company and owner of the South China Morning Post, has announced tie-ups with hospitals for smart diagnosis platforms. In October Alibaba Health launched its first AI medical lab in cooperation with affiliate hospitals of Zhejiang University and Xinhua Hospital. It has also announced a blockchain-enabled public platform to serve as a secure data sharing network for hospitals.

The China-Japan Friendship Hospital, which in March launched an AI enabled assistive diagnosis platform for skin cancer, has received more than 10,000 inquiries from doctors wanting to adopt automated consultations. “There are over 20,000 patients in China diagnosed with melanoma each year, however many of them only find out when it’s too late,” Cui said.

“The algorithm is now ripe, and it’s only a matter of time before we are able to transfer what the machine has learned into diagnosis of other skin diseases,” Cui said, adding that the team is working on adding one new skin disease every three months to the platform.

While the technology marches ahead, regulators are lagging. None of the country’s AI-enabled diagnosis services have received approval from the China Food and Drug Administration – a prerequisite for commercial adoption. The assistive diagnosis systems at West China Hospital and China-Japan Friendship Hospital are experimental and currently free of charge, so don’t require approval from the authorities.

“We want to show the industry what an AI-empowered diagnosis and treatment system will be like,” said Ni of Yitu, adding that while its lung cancer programme is likely to win approval next year, the process has been “difficult to manage” due to regulatory requirements.

Even with the lag in regulation, patients are benefiting. Shi, the Shanghai doctor, was able to identify a potential malignant condition in a 68-year-old female patient after the Quality Skin app indicated a 70 per cent chance of the most common form of skin cancer. Since then, has used it on a daily basis.

“Once you start working as a general practitioner, it’s hard to keep track of the different disciplines,” Shi said.