Live streaming may be booming in China in a post-pandemic world but only a few make it to the big leagues

- The pandemic has seen live streaming become a major new marketing channel for many brands in China after lockdowns

- However, while many live streamers enter the market in China with dreams of hitting it rich, only a few make it to the big leagues

Before the coronavirus pandemic hit, He Zhiqing supplemented his income as a factory owner in the southern Chinese city of Zhuhai with a lucrative side business – live streaming daily life with his wife and their triplet daughters.

Within three years of starting, He and his wife Lin had more than four million online followers who tuned in regularly to watch the family on social media platform Douyin, the Chinese version of ByteDance-owned Tiktok. A well-known diaper brand even offered He 8,000 yuan (US$1,200) to make a 45-second promotion video for their products.

In a good month, the couple could earn as much as 200,000 yuan from advertising and live streaming – not an insignificant sum when some 40 per cent of China’s population survive on a monthly income of 1,000 yuan.

But since January, after the pandemic forced shops to close and pushed more sales online, the family has faced increased competition from other live streamers and the money is not as good as before.

“It’s been tough after the pandemic compared with last year,” said He. “Many movie stars are also live streaming … in the past with fewer people it was easy to be seen, but now there are so many people in this field.”

The pandemic has seen live streaming become a major new marketing channel for many brands in China after lockdowns and social distancing measures closed shopping malls nationwide. But increased competition and more professional content is pushing many ‘mom-and-pop’ live streamers to one side in favour of top steamers with large followings, who are picking up the lion’s share of income.

Homes, trucks and even rocket launches are sold via live streaming in China

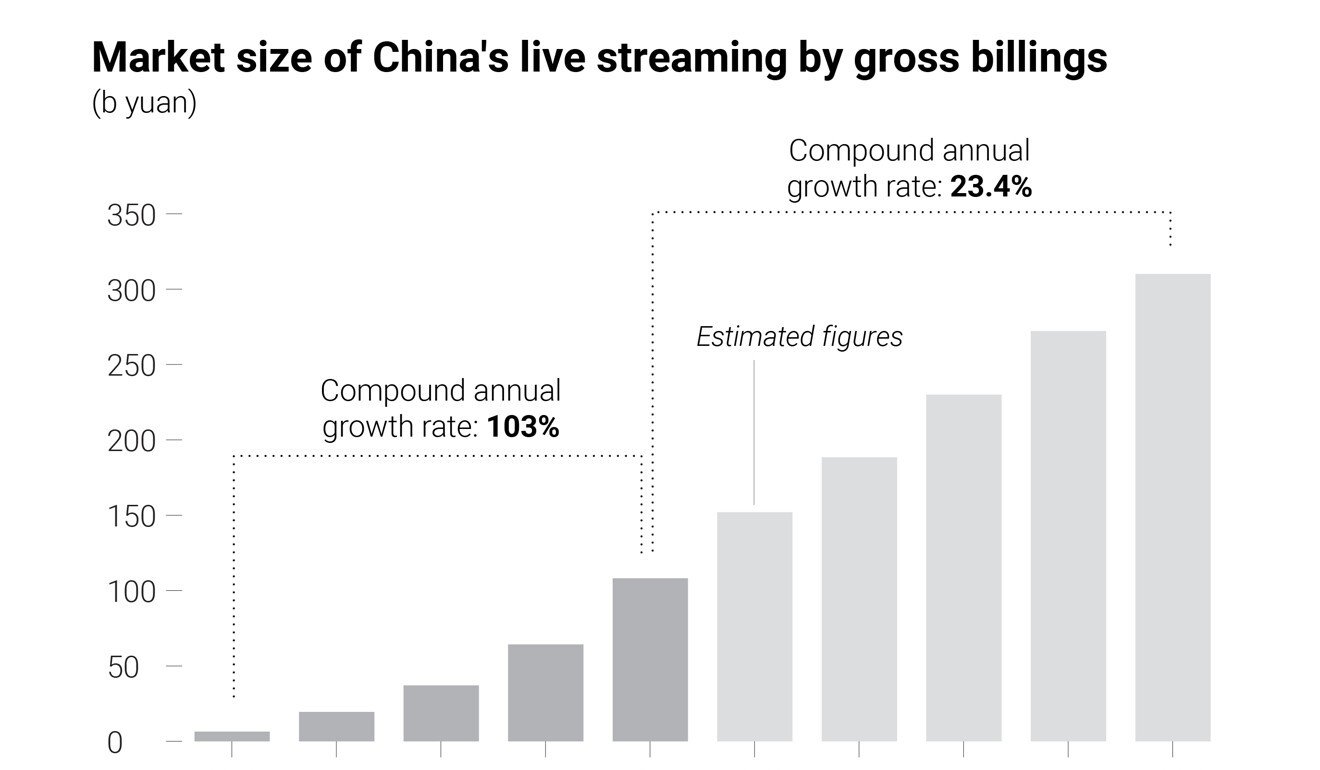

China’s live streaming industry has expanded sixteen-fold between 2015 and 2019 to 108 billion yuan, as measured by total billings generated from sales of virtual items by live streaming platforms to viewers. That market could reach 310 billion yuan in 2024, according to an industry report from consultancy firm Frost & Sullivan. This value does not include income from e-commerce streaming, advertising, and platform membership subscriptions.

At the same time, the number of live streaming users in China has doubled from 2015 to nearly 470 million last year, and is expected to reach almost 640 million in four years’ time. The number of paying users grew nine-fold to 36 million between 2015 and 2019, and is estimated to hit 60 million in 2024, according to Frost & Sullivan.

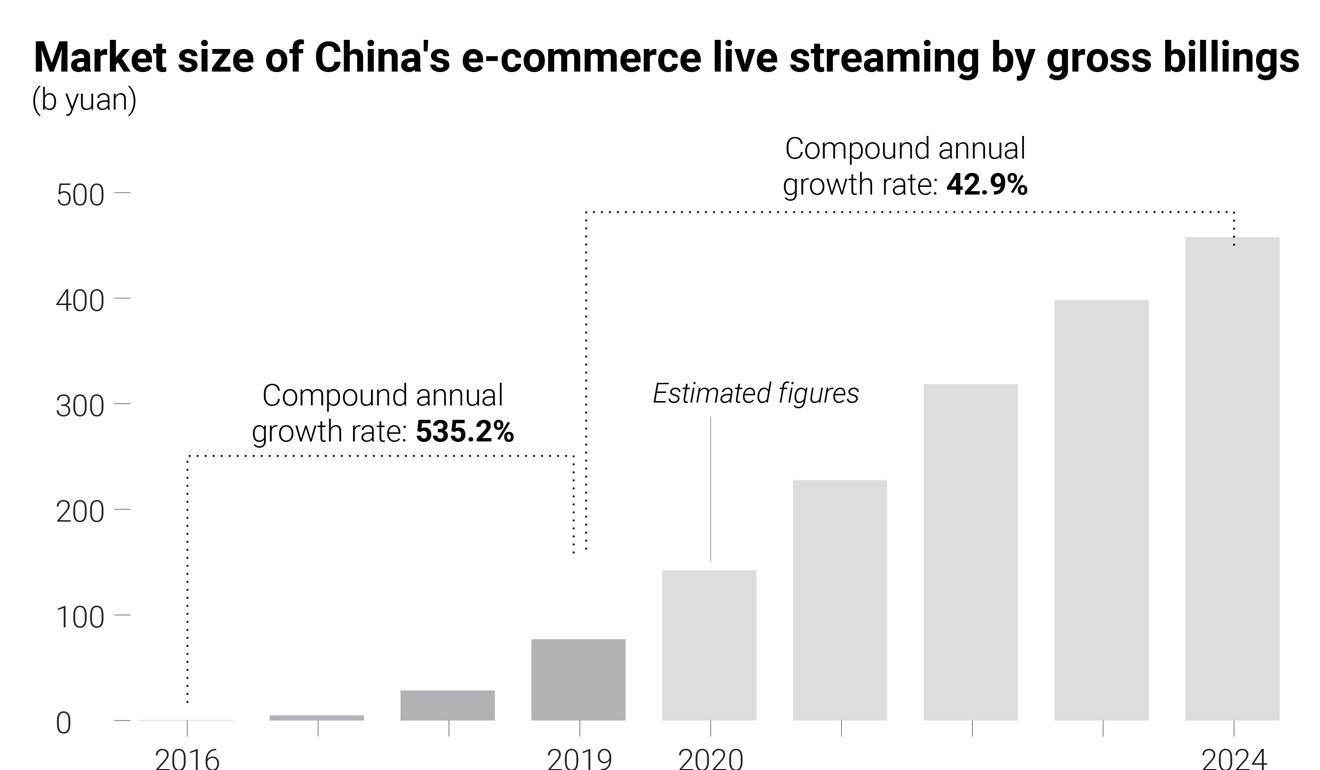

The nature of live-streaming has also changed, moving from entertainment and gaming into broad e-commerce, with everything from lipsticks, perfumes to food items and luxury goods now being sold via live streaming formats. However, while many live streamers enter the market in China with dreams of hitting it rich, and some like He enjoy initial success, only a few make it to the big leagues.

“Being a live streaming broadcaster is definitely a good career choice, but like any other promising industry, the competition is fierce and brutal,” said Zhang Dingding, an internet industry commentator and former head of Beijing-based research firm Sootoo Institute. “The barriers to entry are lower for ordinary folks to join live streaming, but the industry will move in a more professional direction where grass-roots live-streamers will find it harder and harder to compete.”

Top live streamers in China, such as Li Jiaqi and Viya Huang, can garner tens of millions a year from product sales, advertising and virtual gifts. However, streamers on average made less than 1,000 yuan per month in the country during the first half of 2019, according to data from seven major entertainment streaming platforms compiled by zhaihehe, an industry media outlet. And top streamers, accounting for 0.7 per cent of the total number, earned more than 60 per cent of total income.

China’s advertising industry issues rules for live streaming e-commerce

On Momo, a major social and live streaming platform, only 24 per cent of streamers earned a monthly income of more than 10,000 yuan last year, according to its own data. Boss Zhipin, a Chinese online job listing site, said in a half-year industry report this year that more than 70 per cent of live streaming hosts worked 10-12 hours a day but made less than 10,000 yuan a month.

Another man from Shijiazhuang, the capital and largest city in northern Hebei province, surnamed Gao, said he started to make short videos and live stream in 2017. He now has a four-person team and has created multiple accounts to cover entertainment, expert opinions and enterprise – but he has yet to make it rich.

“If there are 100 people doing a live streaming show, at least half of them can’t make any money and the rest of them can only make some money – the same as working in an office, making 5,000 to 6,000 yuan per month.” said Gao. “Only very few people can make a year’s salary via one live streaming show.”

“Of course, I dream that I will have many followers one day, because if I don’t have this dream, I will not make it,” said Gao, who has around 100,000 followers on Douyin.

Gao paid thousands of yuan and flew to Shenzhen in June to take a two-day class on how to become rich on Douyin, China’s most popular short video and live-streaming platform. The course was “OK”, he said, although he is still trying to make his big breakthrough by operating through multiple accounts.

Unlike many who live stream from their own rooms, Yin Ran, 25, is a full time live streamer at a firm in Shanghai, selling luxury products from bags to watches with price tags from 3,000 yuan to 200,000 yuan for six to eight hours every day. There is not much time for her eat or drink. Sometimes her assistant will talk in front of camera for a while when she has lunch, because there has to be someone on camera throughout a whole stream, as required by platforms.

The birthplace of WeChat now wants to become China’s live streaming capital

Yin tells a similar story though – she was initially attracted by a big base salary but as the pool of streamers expanded – income has plunged.

“In 2017 and 2018, a good streaming host could earn 20,000 or 30,000 yuan a month without putting in too much effort. Now a starting host can barely earn 2,000 or 3,000 in a month,” said Yin, who nevertheless said the number of people in China who can fork out up to 400,000 yuan for a luxury handbag is higher than you may imagine.

Many live streamers belong to associations, which act as their agencies to train them and promote their content on streaming platforms while taking a cut from billings attributed to streamers. Happy Entertainment, one of the biggest live streaming associations in China with a market share of about 2 per cent, said its revenue sharing with signed streamers ranged from 3 to 25 per cent, according to a prospectus submitted to the Hong Kong stock exchange this year.

He and Lin, parents of the triplets, joined such a live steaming association but later left, saying they did not find it useful. They are still trying to find a balance between looking after their kids and earning money, and now travel to Hangzhou regularly to help brands there sell their baby clothes via live streaming.

“At the end of the day, there is only one chance for us to spend time with our kids during their childhood, money is less important,” said He.

Additional reporting by Minghe Hu