Wow Way or Huawei? A readable Chinese brand is the first key in unlocking America’s market

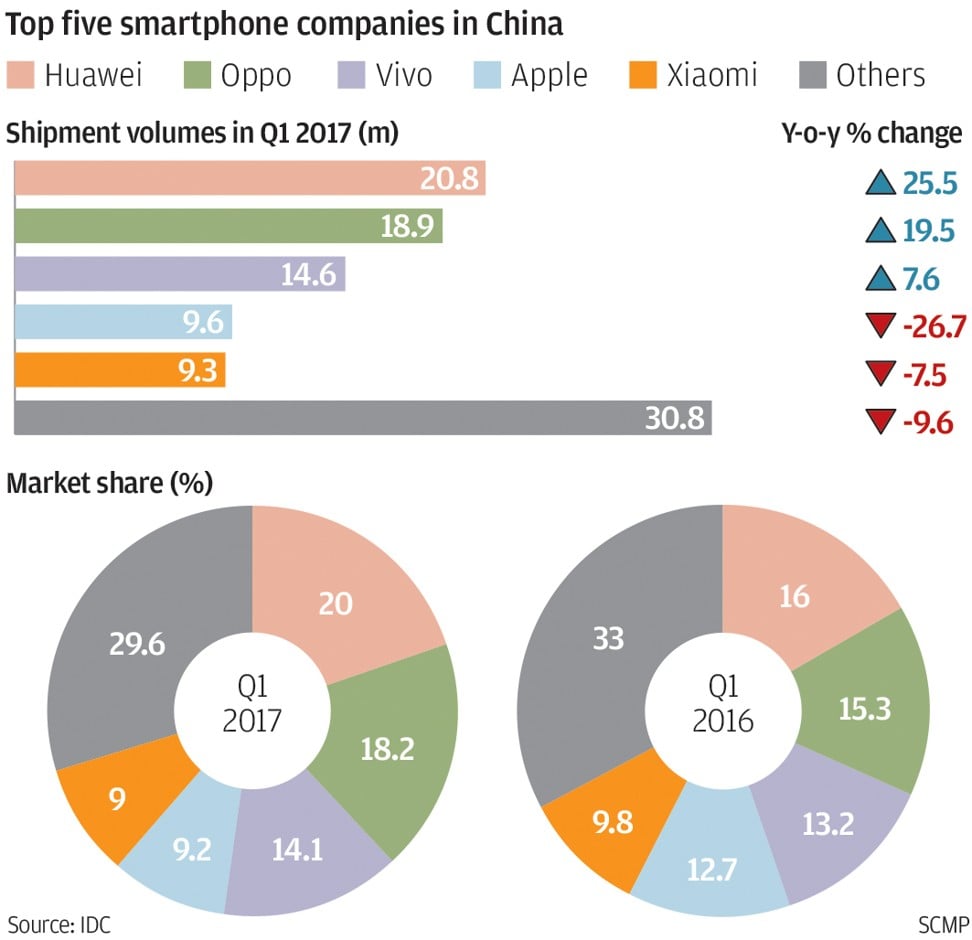

The Shenzhen-based company, which overtook Apple in China in smartphone shipments in June and July last year, had hired Scarlett Johansson and Gal Gadot to advertise its P9 smartphone model for the worldwide market. For the US launch of its latest flagship model, Huawei had a special mission for Gadot, one of the highest-paid and highest-grossing actress of 2017.

“Remember, it’s pronounced Wow Way,” said Gadot, the Israel-born actress best known for her role as the superhero Wonder Woman, in a video clip during Huawei’s coming-out party this week in Las Vegas.

Yes!!! Tell me this didn't just make my day!!! @GalGadot @Huawei #keynote #ww representing #wowway #wonderwoman ♥️♥️♥️ @booredatwork pic.twitter.com/cpU3PxrFNP— Stephanie Yong-Pratt (@BooredFemme) January 10, 2018

Huawei, founded in 1987 by Ren Zhengfei in southern China, is the world’s largest maker of telecommunications equipment. Its name, composed of two Chinese characters, can be translated literally into “Chinese Achievement” in English. These are characters any elementary Chinese speaker can read, or understand.

Not so for non-Mandarin speakers.

Chinese speakers read letters differently from native English speakers. Words like Huawei and Xiaomi, rendered in Pinyin, or the romanisation of Chinese characters, would be difficult to make out, according to Professor Wang Guizhen, who specialises in linguistics at Guangdong University of Foreign Studies.

“Hua sounds different when pronounced in Chinese, compared with English,” Wang said. “It would be difficult for native English speakers to pronounce these letters together, unlike Chinese speakers who are used to them.”

Show attendants at this week’s CES in Las Vegas, some of the most informed and worldly people at the apex of consumer technology, struggled when asked to pronounce Huawei.

Huawei isn’t alone. Xiaomi, aiming to revolutionise China’s consumer electronics along the style of Apple, is almost impossible to pronounce. Xiaomi literally means “little rice.”

Or take Tsingtao Beer, arguably the most internationalised among China’s brewers, its distinctive green bottle often the only Chinese brand found anywhere outside mainland China. Its name, spelt in the Wade-Giles system for romanising Mandarin, is the name of its home base of Qingdao city in Shandong province.

Chinese brands need to be “something that roll off the tongue easily” to succeed, said Shaun Rein, founder and managing director of the China Market Research Group in Shanghai. Names like Huawei or Xiaomi, which “haven’t created English names that Americans and western Europeans can memorise or pronounce easily” have a bigger problem breaking into the market, he said.

Americans spent US$14,564 per person on retail spending in 2014, more than three times the per-capita spending by Chinese consumers in the same year. That underscores the attraction of the consumer market in the planet’s biggest economy, even if its population is a quarter of China’s size.

For Huawei, whose 2016 revenue jumped 32 per cent to 521.6 billion yuan (US$80 billion), the smartphone is but the thin end of the wedge for a bigger ambition.

“Consumer devices are a way to gain acceptance in the US,” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director at the European Centre for International Political Economy, an independent think tank. “It’s essentially a public relations write-off to open up the network equipment market, where the actual profits are made.”

There are exceptions. DJI, the world’s largest producer of recreational drones, is headquartered in Shenzhen in southern China. Its full name, spelt out, is Da Jiang Innovations, inspired by the Chinese adage “Great ambition has no boundaries”.

But the company rarely goes by its full name in English, preferring to obscure its origins. It has an estimated 75 per cent share of the world’s market for drones, with the US among its biggest market.

Or take Byton, the Chinese electric vehicle that’s aiming to put Tesla’s Model X in its rear-view mirror, with a price tag that’s 40 per cent cheaper than the American model.

With reporting by Meng Jing in Beijing, Bien Perez in Hong Kong, Chua Kong Ho and Sarah Dai in Las Vegas.