Space exploration’s next frontier: remote-controlled robonauts

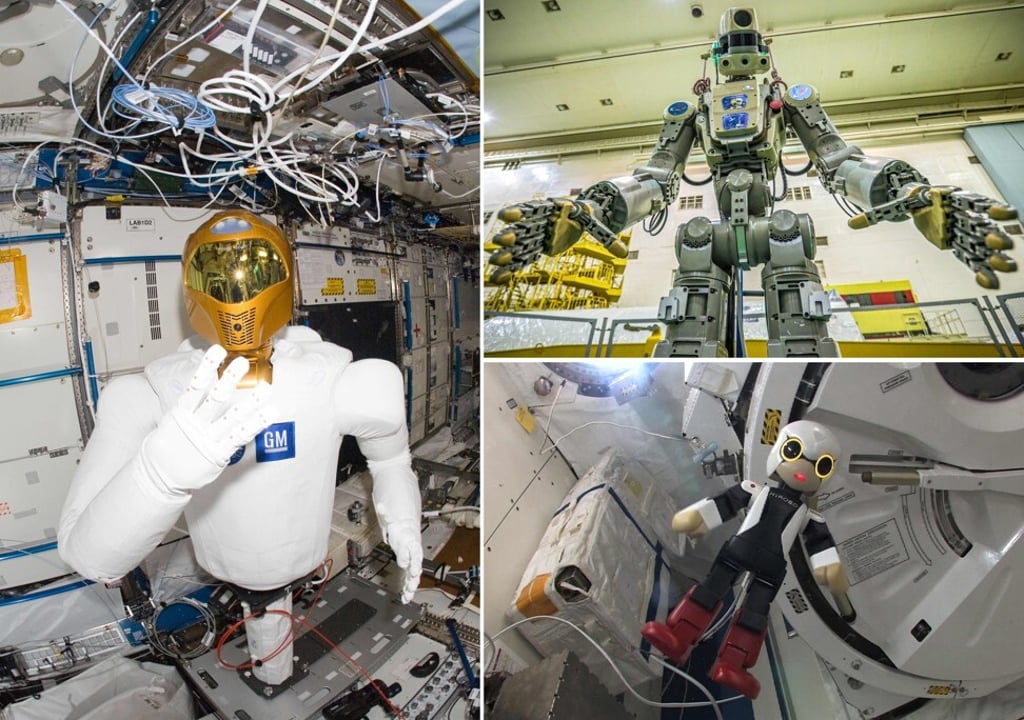

- Robonauts, which are remotely operated from Earth, are designed to handle tasks that normally would require an astronaut to go into space

- These hi-tech avatars are expected to help Nasa lower the cost of efforts to open up the International Space Station to private businesses and its Artemis mission to send astronauts back to the moon

As Japan’s second female astronaut to fly up in the Space Shuttle Discovery, Naoko Yamazaki did not expect to spend a quarter of her time dusting, feeding mice and doing other menial jobs.

It can cost more than US$430 million a year to keep an astronaut in orbit, according to three-year-old start-up called Gitai. It is only possible to keep humans alive in outer space because of the money and effort poured into ensuring their safety. One way to bring down the cost and risks is to send an avatar – a remotely controlled robot.

“There’s a need for robots that can help us,” Yamazaki, 49, said. “Eventually, we should be able to do those tasks remotely or have them take over altogether.”

As Nasa opens up the International Space Station to private businesses and embarks on the Artemis mission to send astronauts back to the moon, there is a growing recognition of the need to keep spending under control, even as space-exploration projects grow increasingly complex.

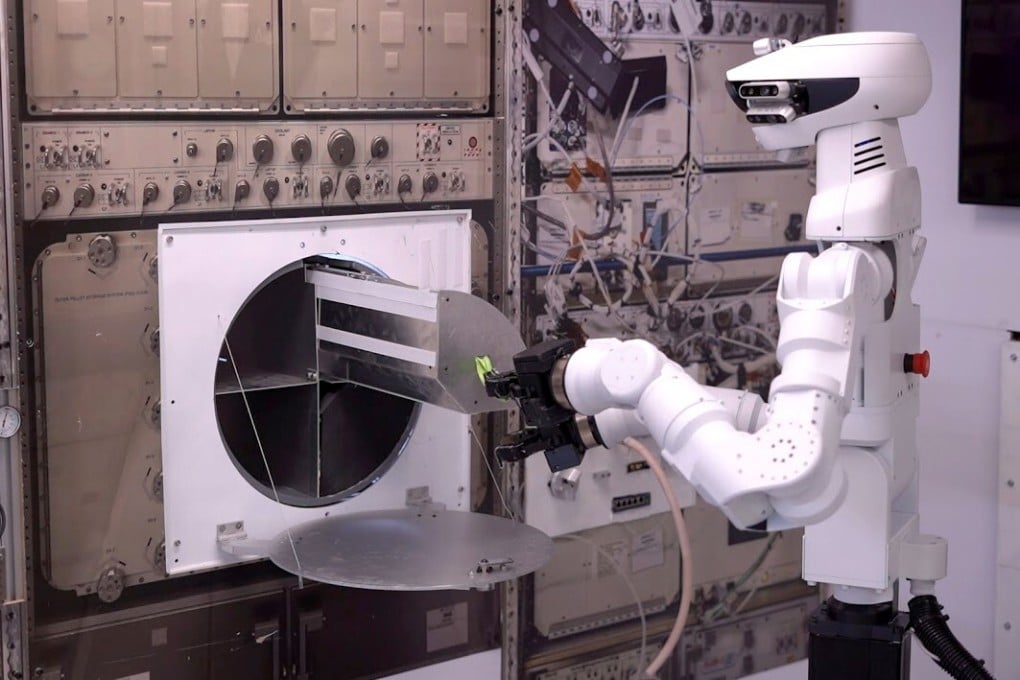

That is where avatar technologies come in. Like a drone pilot, an operator equipped with wraparound screens or a virtual-reality headset will be able to move mechanical arms or an entire robot from far away. The building blocks already exist; the trick is to bring them together with software to make it all work. That is one reason the space robotics market is projected to reach US$4.4 billion by 2023.