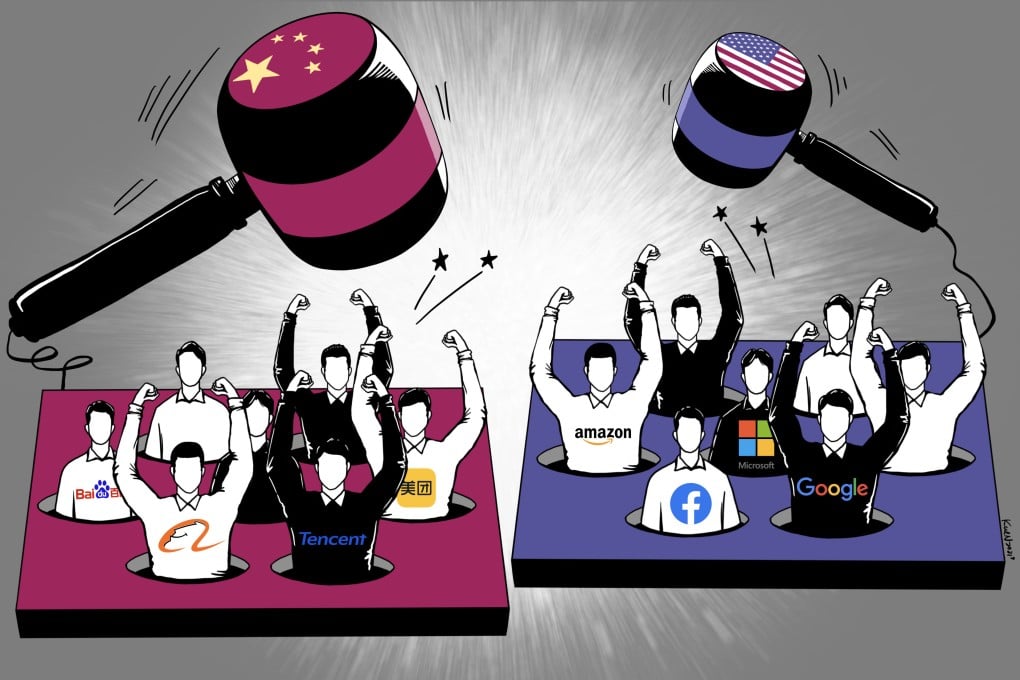

What differentiates China’s Big Tech antitrust challenges from those of Google, Amazon, Facebook or Apple

- The antitrust investigation against China’s Big Tech companies appear to share many similarities with inquiries in other parts of the world

- Chinese companies’ unique challenges include dependence on their home market and a more opaque policy environment

Technology giants around the world are facing increasingly higher regulatory barriers to expansion. Long uneasy with monopolies, governments and consumers in North America, Europe and now in China have pushed back against Big Tech’s increasing concentration of market power.

“Closer scrutiny of the tech sector is not uniquely Chinese, and the seriousness of antitrust enforcement is not particularly new,” said Marcus Pollard, antitrust and foreign investment counsel at the law firm Linklaters, adding that the main concern for regulators had been whether Big Tech could use their market clout to exclude competitors at the detriment of consumers. “Alibaba is obviously a high-profile statement of intent by the regulator of their mission to keep markets open with diverse choices for consumers.”

In both China and the West, the rise of Big Tech went mostly unchecked for years, as many extolled the role played by technology in economic growth and improving people’s lives. US regulatory scrutiny of tech firms went into abeyance since the 1998 antitrust case against Microsoft was ultimately overturned and settled out of court, failing to break up the software vendor which powered nine of 10 personal computers around the world.

Scrutiny did not resume in earnest until about two years ago, as policymakers and consumers became aware of how technology giants – especially the internet behemoths operating everything from search to shopping and social interactions – had come to govern people’s lives and public discourse. Worse, as the incumbents grew larger, they were starting to squeeze out smaller competitors and start-ups.