US-China tech war: In the battle for talent, the US is ‘shooting ourselves in the foot’

- Justice Department’s ‘China Initiative’ pursuit of suspected tech thieves and spies is chilling the climate for scientists studying and working in the US

- The crackdown comes as the US faces a ‘severe shortage of digital talent’, a member of a US commission on artificial intelligence says

In the fourth of a five-part series on US-China technology policies, Jodi Xu Klein looks at a critical, yet often underappreciated, component: how important talent is to win the future in tech and how US policies aren’t helping to attract and keep it. The first part, on how China policies vary in different US agencies, is here; the second part, on Huawei Technologies’ prospects, is here; the third, on Chinese supply-chain woes, is here.

On the cold early morning of February 27, 2020, Hu Anming, a 52-year-old nanotechnology professor at the University of Tennessee, opened his door to unexpected guests: eight plain-clothed and fully equipped FBI agents arrested him. Before they took him away in handcuffs, Hu was allowed to take his diabetes medicine.

Sixteen months later, Hu’s case went on trial in Knoxville, Tennessee, in early June. After a week of testimony, a 12-person jury split their votes without convicting Hu of any of the six counts he faced – three of wire fraud, three of making false statements, stemming from the prosecution’s contention that Hu had applied for and received grants from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration without disclosing his work with a Chinese university. A three-year federal investigation that started on suspicion of espionage had ended with a judge declaring a mistrial.

US ban on Xinjiang solar products heaps pressure on supply chains

For Hu and his family, it was barely a victory. Hu, a China-born naturalised Canadian citizen, was suspended from his tenured position at the Tennessee university, where he worked since 2013, shortly after his arrest. Years of phone records and emails were sifted through without much protection of privacy. With legal fees in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, the case, which critics have called racial profiling with flimsy evidence, has changed their lives forever.

“Anming sold everything at Knoxville. He is living in an empty house,” said Ivy Yang, 51, Hu’s wife, who is also Chinese-Canadian. “I think coming to the US was a mistake. I hope he can come back to Canada. You never know when you will step on landmines.”

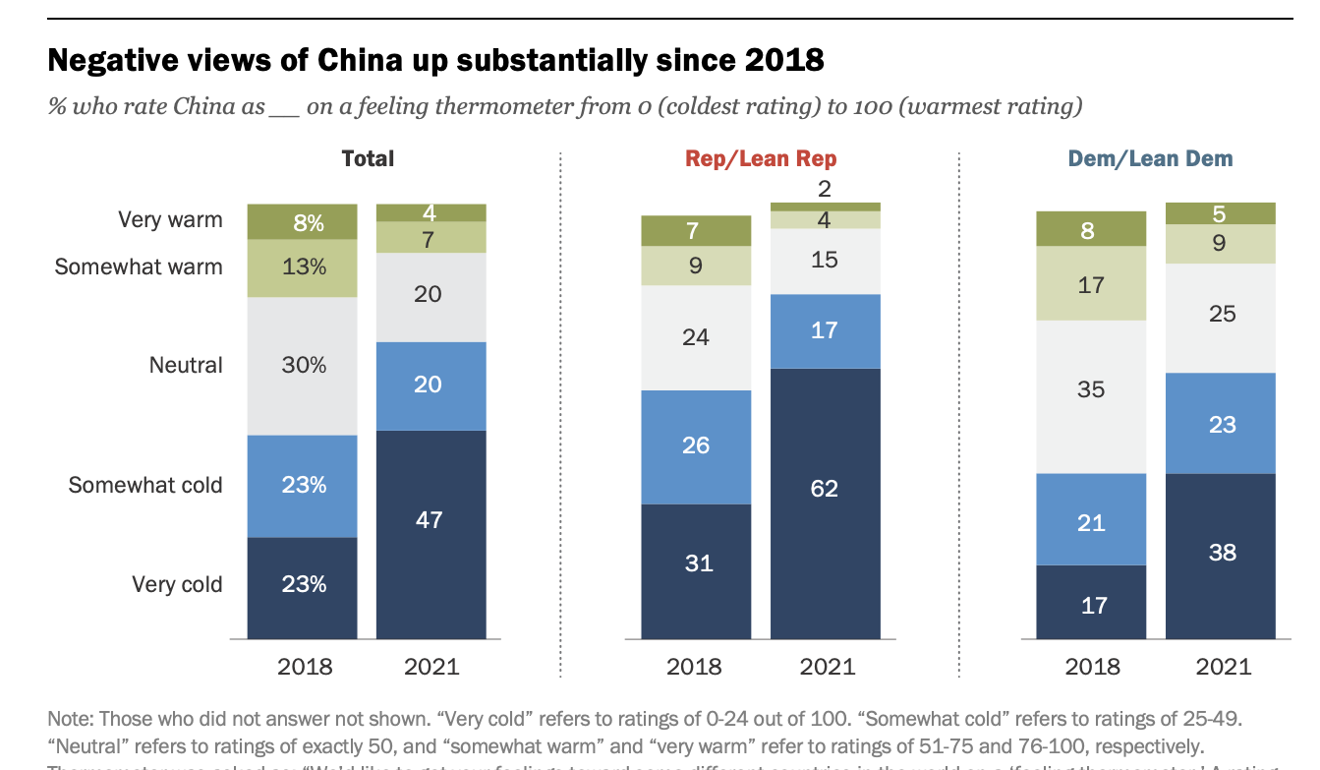

For scientists and researchers of Chinese descent in the US, that landscape has grown a lot more difficult to navigate safely since 2018. In November that year, the US Department of Justice launched its “China Initiative”, a Trump administration programme to identify and prosecute anyone it accused of stealing trade and tech secrets for Beijing.

The intensifying US battle against China’s technological ascent – sometimes through illegally obtained tech and other secrets – has put pressure on law enforcement, occasionally casting an overly wide net to catch the next spy.

The geopolitical competition between the US and China is often described as a clash over technology, economics, and military, but it fundamentally depends on the ability of each country to attract and retain talent as well as train a workforce for the future. Many analysts worry that putting Chinese-American scientists collectively under federal scrutiny and blocking Chinese students from coming to the US will chip away at American tech leadership.

US Justice Department officials call their ‘China Initiative’ a success

“Framing the problem of geopolitical competition with China as an excuse to make us more closed will only shoot ourselves in the foot,” said Mary Gallagher, director of the Centre for Chinese Studies at the University of Michigan. “If the United States becomes more shut down to international students, this will harm the United States, and it will really not hurt China. The students and the researchers will just go to another country. The UK, Australia, and Canada will all benefit from our mistake.”

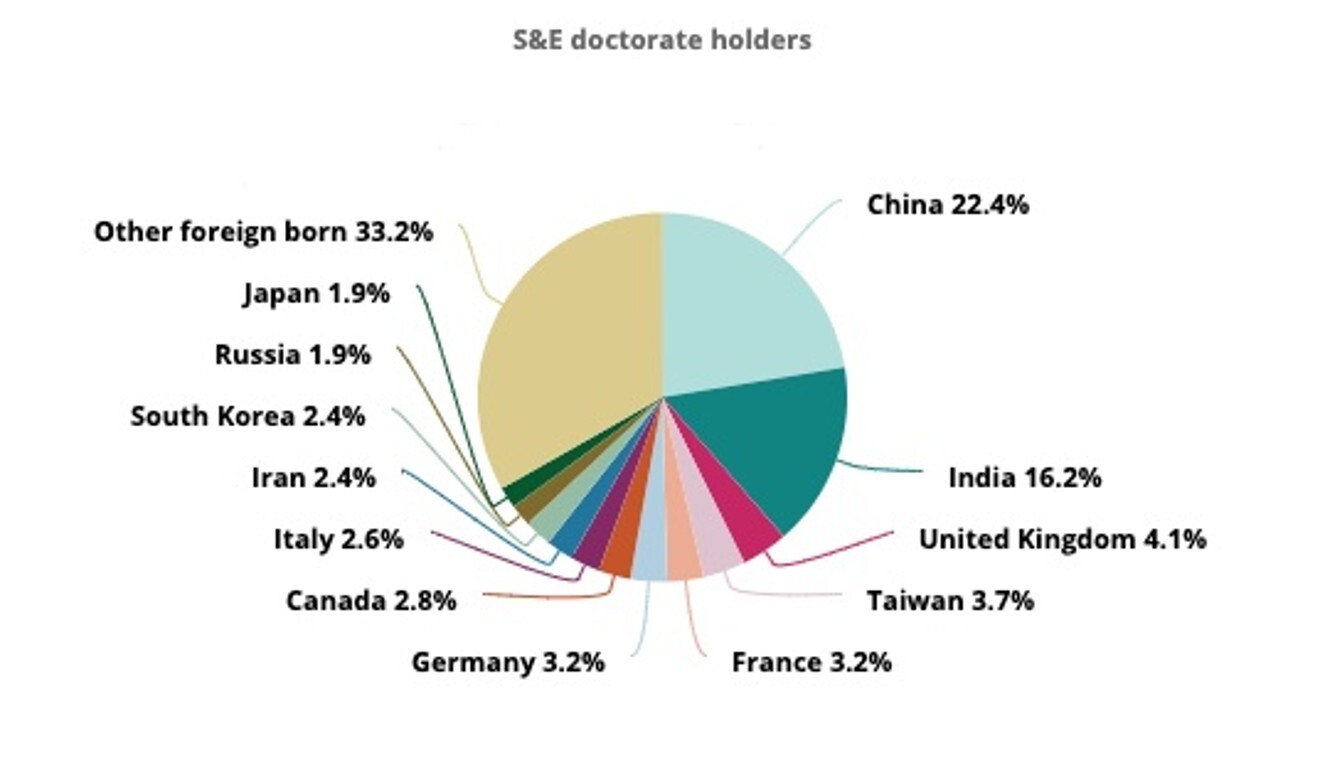

Foreign-born scientists and engineers are a critical part of the US workforce. Among individuals working in the tech fields in 2015, 45 per cent of those with doctorate degrees were foreign-born, according to the National Science Foundation (NSF), the latest year for which data is available. That was up from 39 per cent in 2003.

But with a battery of cases targeting these scientists and students, many are rethinking their future in the US.

“There is a level of fear among the Chinese-American scientific community right now that is very palpable,” said Rory Truex, an assistant professor at Princeton University studying Chinese politics. “All of a sudden, there’s just been this complete sea change. Those folks, most of whom are Chinese-American, feel like they don’t know what they can do any more.

“Many of these people have come from China to escape the Chinese Communist Party. This idea that their loyalty is a question or that they are now being the target of the US government is deeply problematic and insulting.”

There is a level of fear among the Chinese-American scientific community right now that is very palpable

China has, in fact, acquired trade and tech secrets through illegal means. In November, Sun Wei, an engineer who had worked for aerospace giant Raytheon, was sentenced to more than three years in prison after pleading guilty to having exported sensitive military-related technology to China. In April, Qin Shuren, a Chinese national, pleaded guilty to illegally exporting US marine technology to Northwestern Polytechnical University, a Chinese college that the Department of Justice said is heavily involved in military research.

While tech theft is real, US federal courts have also thrown out cases because of the lack of evidence. Temple University’s physicist Xiaoxing Xi, University of Virginia underwater-robotics researcher Hu Haizhou, and hydrologist Sherry Chen of the National Weather Service office in Wilmington, Ohio, were recent examples.

In other cases, indictments were narrowed or reduced to lesser charges, such as in Hu’s case, after investigations failed to turn up enough evidence of espionage. Regardless of the outcome, the accused either lost jobs, ended up in debt for hefty legal fees, or suffered reputation damage.

04:26

Chinese-American scientists fear US racial profiling

“The FBI’s thousands of investigations under the China Initiative have not unearthed widespread criminal activity among researchers. Only a handful of cases have actually been for economic espionage or trade secret theft, more cases have been about false statements such as failure to disclose relationships with entities in China,” said Margaret Lewis, law professor at Seton Hall University. That pursuit, Lewis said, “has thus far continued under the Biden administration.”

Shortly after US District Judge Thomas Varlan declared a mistrial in Hu’s case on June 16, DoJ spokesman Marc Raimondi, said the department would “continue following the facts and evidence and bring cases accordingly” when it comes to “investigations into criminal malfeasance with a nexus to the People’s Republic of China”.

During the Trump administration, the US made it harder for foreign students to enter the country, changing the H-1B visa system for temporary workers and imposing restrictions on the spouses of US visa holders. More than 1,000 Chinese students had their visas revoked following a May 2020 ruling aimed at Chinese nationals suspected of having ties to the military.

“I’ve seen a level of deep hostility that really borderlines, if not crosses, xenophobia. And I worry about that because we want to be bringing in the best and brightest from all over the world,” said Representative Andy Kim, Democrat of New Jersey, a Korean-American who sits on the House Foreign Affairs and Armed Services committees.

If more Chinese scientists at American labs decide to leave the country, it will catch the US just as it needs the most talent it can lay its hands on.

Mignon Clyburn, a member of the US National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence, said that one of the many challenges the US faces is “a severe shortage of digital talent”.

“Not only does the government not have enough technical talent, but our government isn’t doing enough to bring in more talent into its ranks,” said Clyburn, who led the Federal Communications Commission during the Obama administration.

Our government isn’t doing enough to bring in more talent into its ranks

Clyburn suggested that the government establish a talent pipeline: the United States Digital Service Academy. Much like the nation’s military academies prepare officers, it would train the next generation of leaders of the US digital workforce.

Big Tech has been among the first to feel the talent pinch. In May, Google, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, Twitter and tech trade associations submitted an amicus brief in a federal case supporting the right of spouses of H-1B visa holders to work, arguing that the US needs an immigration system that lets skilled foreign workers into the country to foster innovation.

In April, Morris Chang, founder of the Taiwan silicon-chip giant TSMC, warned that a lack of skilled workers in the US could jeopardise its planned US$12 billion plant in Arizona.

“We had to try hard to scout out competent technicians and workers in Arizona because manufacturing jobs have not been popular among American people for decades,” Chang said.

China has been attracting tech talents back home with its Thousand Talents Plan, an initiative began in 2008, that features significant financial incentives. In its latest five-year plan for 2021-2025, Beijing said it would explore an immigration policy to attract non-Chinese talent.

China mutes volume on Thousand Talents Plan as US spy concerns rise

As of April, according to a KPMG report, more than 10,000 companies in Shanghai have received government approval to go hire foreigners who possess innovative science skills, under an easier set of criteria with less restrictive age range and expanded eligibility of applicants.

China regards the competition for talent a crucial component in the tech race. Chinese President Xi Jinping said repeatedly that “human talent is the first resource” in the country’s push for “independent innovation.”

“We must cast our eye upon the needs of national strategy,” Xi said at the 13th National People’s Congress in 2018, adding that China had to “attract top-flight scientific and technological talent from at home and abroad”.

A heated climate often accompanies such high-stakes rivalries, Ryan Hass, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute in Washington, noted. “When there is rising nationalism and increasing great power competition, racism often follows,” he said. “We need to try to break this cycle.

“The question I would ask is: Do we want the next generation [of tech talent] in the United States or in China?”