Controlling hearts and minds: China cracks down on content algorithms to make sure the Communist Party is still boss

- Jinri Toutiao relied on computer algorithms to recommend interesting and important articles to readers, not reporters or editors

- Less than a decade on, Zhang’s news aggregator would grow into ByteDance, the world’s first hectocorn, a private company valued at US$100 billion

The third part of a series on China’s antitrust crackdowns in the technology industry looks at the regulatory scrutiny on the algorithms that power recommendations in such applications as news aggregators, video sharing platforms and live-streaming apps.

When Zhang Yiming first went about creating Jinri Toutiao in 2012, he had in mind a news service that relied on computer algorithms to recommend interesting and important articles to readers, not his own reporters or editors.

Jinri Toutiao, which translates to “Today’s Headlines” in Chinese, “can continuously learn your interests,” Zhang said in 2014. “No one sees the same page, and the longer you use it, the better it understands you, the better it recommends to you.”

Toutiao famously described the electronic front page of its algorithm-based news aggregator as having a thousand pages for a thousand faces. Many of China’s technology companies are now following ByteDance’s footsteps in applying increasingly sophisticated algorithms to make more tailored pitches to internet users, pushing content that is most likely to satisfy their consumption needs, along with links to advertisements they are most likely to click, providing them with the deals they are most likely to sign up for.

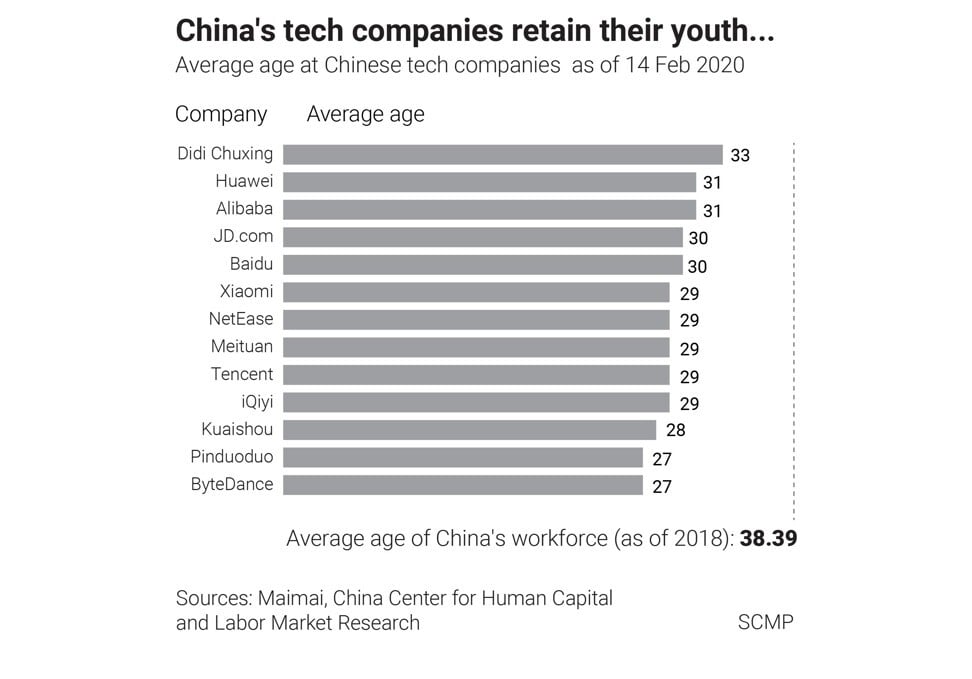

In China’s internet sector, where one billion mostly smartphone-connected internet users vie for instant gratification for everything from information to food delivery and financial transactions, the use of algorithms is one of the cornerstones of success of Big Tech firms.

“What regulators worry about is losing control over content,” said Fang Kecheng, assistant professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s School of Journalism and Communication. “The traditional way of controlling content through controlling the [reporters and editors] who produce it can’t be directly used on algorithms.”

Hence, the Chinese authorities are coming up with the world’s first government regulation dedicated to “algorithm empowered recommendations” to curb the use of technology, and to hold owners of these algorithms accountable for any content that run contrary to state policies.

According to a new draft rule published by the Cyberspace Administration of China last month, Chinese internet users will be empowered to say no to targeted alerts, and it puts additional legal responsibilities on algorithm owners in the areas of news, search, gaming, e-commerce and short video.

Service providers that “have the ability to influence public opinion” will need to go through a registration procedure with authorities, according to the draft rule, which is open to public feedback but likely to become official regulation.

This comes after China’s top state propaganda organs, which decide what people can read and watch in the country, jointly urged better “culture and art reviews” in China earlier this month by limiting the role of algorithms in content distribution.

Along with a rigid censorship regime that patrols content sources, from removing films and television episodes starring Chinese actors and actresses who have run afoul of state policies to shutting down the social media accounts of unsanctioned influencers, Beijing wants to use content platforms as the channels to inject “positive energy” and “mainstream values” into the online world. These include such values as loyalty to the Communist Party’s leadership and an admiration of the Chinese military.

“Algorithm recommendations are closely related to every citizen,” said Gao Yandong, a researcher at the Institute for Public Policy of Zhejiang province. “But tech firms are often guilty of misconduct in the way they use algorithms, such as charging different prices to different people based on consumer profiles and manipulating hot topics on social media platforms.” As such, China’s algorithm rule “provides a law enforcement basis to regulate these behaviours,” he said.

For some Chinese consumers, intrusive algorithms are now a fact of life. Li Yuzhou, a 27-year-old Shanghai resident, said that she spends roughly 30 minutes to an hour on content apps every day that use algorithmic recommendation, including Douyin, social commerce app Xiaohongshu and question app Zhihu.

While she generally regards the apps as entertaining and informative, she also finds them annoying when the content on her feed gets too repetitive after they’ve learned what she is most likely to click on. But Li said that even if she’s given the chance to turn off the algorithmic recommendation, she wouldn’t.

“Without recommendation algorithms, it would keep feeding me things I’m not interested in, which is also not ideal,” Li said.

However, Beijing’s wariness of letting technology decide what people read and watch is not a new phenomenon.

In 2018, the Chinese government shut down Neihan Duanzi, a joke sharing app also owned by ByteDance with 200 million users , accusing the smartphone application of spreading “vulgar content”.

Zhang made a public apology at the time and vowed to improve by hiring thousands of Communist Party members to help censor content. In fact, for China’s online content providers, censorship has always been part of the equation.

In 2019, when the South China Morning Post visited Beijing-based Inke, a large live-streaming company, the company said up to 60 per cent of its workforce comprised staff working in what was dubbed the content moderation team, responsible for taking undesirable content off air. That included any content related to politics, sexual acts, violence and terrorism, breaches of which would invite severe punishment by regulators. That meant it was the platform’s responsibility to ensure no such content would be distributed.

Still, algorithms should allow for some human interference, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), the internet watchdog agency, said in a 2019 regulation specifically for content. In one article aimed at explaining the rules, published by the regulator’s journal, it was stated that content recommendation based on algorithms poses a risk to national security because it could potentially “affect political progress and exacerbate political polarisation”.

The article referred to Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica scandal as an example, where in 2018 a private firm was found to have used the personal data of Facebook users to affect political elections.

In late 2019, Facebook agreed to pay £500,000 (US$692,300) in fine to UK authorities for breaching data protection laws by allowing Cambridge Analytica to obtain the data of up to 87 million people worldwide without their consent, and using that data to influence elections in several countries.

Wong Kam-fai, a professor in engineering at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and one of the first batch of national experts appointed by the Chinese Association for Artificial Intelligence, said different governments have different approaches towards regulating algorithms.

Europe does not have any tech giants, so the regulation is more focused on users, while the US has to balance the public interest with the effect stricter regulation could have on large employers such as Facebook and Google, said Wong.

“China has always said that there can be no chaos,” Wong said. “For the government, social stability is a very important factor when they think of new legislation. You can see that even though these three places [US, Europe and China] all want to [regulate algorithms], they have different starting points.”

State-run Zhejiang Radio and Television Group has developed a “new algorithm” to promote “mainstream values” by automatically pushing what it calls “positive energy” content to users. Meanwhile, content from official propaganda channels, such as China Central Television and the People’s Daily, are high on the government’s agenda.

It remains to be seen however, how this modern-day propaganda push will affect the long-term operations of Big Tech.

“The truth is, I lack some of the skills that make an ideal manager,” he said. “I’m more interested in analysing organisational and market principles, and leveraging these theories to further reduce management work, rather than actually managing people.”

“I used to stay on top of new developments in machine learning before 2017, but I haven’t learned much in the last three years,” Zhang wrote in his public letter of resignation.

Additional reporting by Masha Borak