Chinese bitcoin miner exodus faces hurdles as equipment remains stuck from shipment delays, tariffs and legal quagmire

- As many as 2 million cryptocurrency mining machines are stuck in China’s Sichuan province, lawyers estimate, after a government crackdown halted operations

- Miners trying to move to North America are losing millions of dollars while waiting to export machines through complex shipping routes to avoid tariffs

A massive exodus of bitcoin mining equipment from China is facing hurdles as millions of machines remain stuck over complex relocation procedures, according to lawyers handling such cases.

Compounding their troubles is the fact that miners are losing potential revenue each day the machines are offline, to the tune of about 170 yuan (US$26.70) in profit per machine by one estimate. For the largest operations, this means a loss of millions of dollars that can never be recuperated.

Bitcoin miners look overseas amid crackdown in China

One lawyer representing a mining farm owner who once ran hundreds of thousands of machines told the South China Morning Post that his client is under a lot of pressure to get the machines up and running again outside of China. There were at least 2 million mining machines stuck in China’s southwestern Sichuan province by the end of 2021, by his estimate.

Mining farms used to enjoy local government support in Sichuan, where abundant hydropower made it cheap to run such energy-intensive operations. Each mining machine, usually weighing more than 15kg, uses multiple chips to solve complex mathematical problems and process massive amounts of data. This means cheap electricity is critical to eking out a profit. But now a new type of lucrative business has cropped up in the province: logistics and legal services that help miners relocate.

Since the national government made cryptocurrency mining illegal, large mining farms have been left with no option but to relocate. It is nearly impossible to find buyers for all their equipment. While smaller projects may sell what they can and buy new equipment abroad, big operations have found their search for a new destination to be tricky.

The ideal mining locations in China had cheap electricity provided by natural gas or hydropower. The combination of affordable power and an amiable local government has been difficult to find overseas. Russia and Kazakhstan were initially popular options, but they have proven risky locations because of power shortages and inconsistent policies.

Kazakhstan has cut power supplies to several miners, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev earlier this week called for a much higher tax on crypto mining. Last month, Russia mulled banning bitcoin mining and other cryptocurrency activities. However, the government is now moving to regulate cryptocurrencies as an “analogue of currencies” rather than a digital asset.

Despite its power woes, Texas has become one of the fastest-growing destinations for cryptocurrency miners in the world. Governor Greg Abbott welcomed the industry last year, tweeting, “Texas will be a crypto leader.” Some hope that new mining activity will spur new wind and solar energy production to mitigate power woes.

For Chinese miners, though, getting to Texas, or anywhere in North America, is not as straightforward as it seems. Picking a new destination is just the first step of a long process.

A Chinese mining farm, as an external investor, has to negotiate power prices with the local suppliers at the new chosen site, one of the lawyers said. Even once all the terms are settled, logistical issues remain and are exacerbated by transport disruptions during the recent surge in Covid-19 cases.

Direct shipping to the US is also costlier than to other locations because of a 25 per cent tariff put in place by the administration of former president Donald Trump. To avoid this, some owners of mining equipment going to the US are preparing to ship through Malaysia, according to the lawyers. Equipment going to Canada will follow the same path just in case, they said.

With the pit stop in Malaysia, moving machines from China to North America is expected to take one to two months and cost more than US$10 per terahash of processing power, they estimated.

“China’s strict regulations of crypto mining and trading is linked to China’s simultaneous implementation of sovereign digital currency,” said Winston Ma, an adjunct professor at the New York University School of Law and author of The Digital War: How China’s Tech Power Shapes the Future of AI, Blockchain and Cyberspace.

“The US and China have many conflicts today, but there’s one issue on which both superpowers see eye-to-eye: the regulation of stablecoins,” he said.

Decentralised cryptocurrencies like bitcoin, however, behave more like commodities, with valuations fluctuating wildly. When prices surge, it helps offset the high energy costs that go into mining.

In bitcoin’s early days, mining operations cropped up around China, where such activity proved profitable owing to the country’s cheap electricity. As a result, China emerged as an important market for cryptocurrency trading, investment and mining, with some of the world’s largest exchanges like Binance and Huobi having been founded in the country. Several major mining machine manufacturers, including Bitmain, Canaan and Ebon International, are also backed by Chinese entrepreneurs.

Local authorities in places with sufficiently cheap electricity, like Inner Mongolia and Sichuan, even welcomed investors, hoping the burgeoning industry would boost the economy.

In the mountainous areas of Sichuan that border the Tibetan plateau, installations of small hydropower stations made electricity particularly cheap, which was a big lure for mining farms. Average electricity prices could be as low as 0.15 yuan per kWh, according to investors and industry insiders. In the summer, when the region’s valleys are filled with torrential rainfall, electricity is “almost free” because the surplus cannot be stored and would be wasted if not used for cryptocurrency mining, they said.

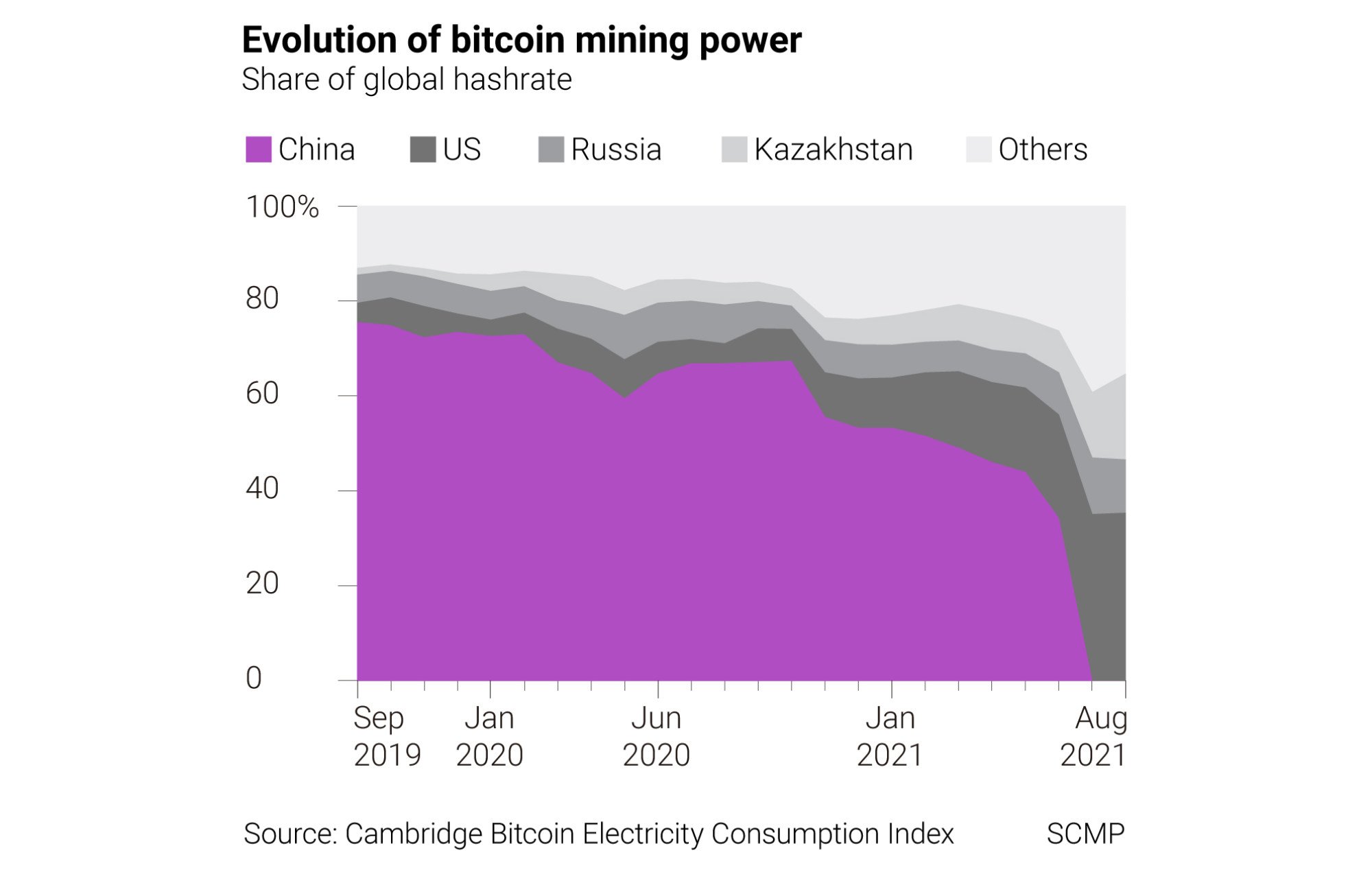

A number of local governments in Sichuan created special industrial parks to house these farms to attract local investment and potentially increase tax revenue. In 2019, Sichuan named six remote areas as “model zones” to absorb extra hydropower. The model was replicated in other areas of the country, which accounted for two thirds of the world’s mining power as late as April 2020.

The high energy consumption of mining activity proved to be a problem for the national government, which aims to reach peak carbon emissions by 2030. The crackdown that kicked off last May has also targeted people supporting the industry.

Xiao was found to have “abused his power” by supporting related enterprises, according to an official statement. He was the first senior party member to be punished for supporting cryptocurrency mining.

Now China has become largely irrelevant to the cryptocurrency world. Even related companies backed by Chinese entrepreneurs have been forced to move their headquarters to other countries.

In August, the US made up 35.4 per cent of the global hash rate, followed by Kazakhstan and Russia with 18.1 and 11.2 per cent, respectively, according to data from the CBECI.

China’s proportion fell to approximately zero, as anyone involved in cryptocurrency mining now faces criminal charges.