Scientists just discovered that NASA flew through a blast of alien ocean water in 1997 — and a US$2 billion mission may soon ‘taste’ it for signs of life

A new spacecraft could ‘sniff and taste’ the water spraying from an icy moon with a giant hidden ocean and analyse it for signs of habitability — and alien life

By Dave Mosher

Scientists have re-examined 20-year-old data from a Jupiter spacecraft, and their discovery may considerably improve the chance we’ll find alien life in the solar system.

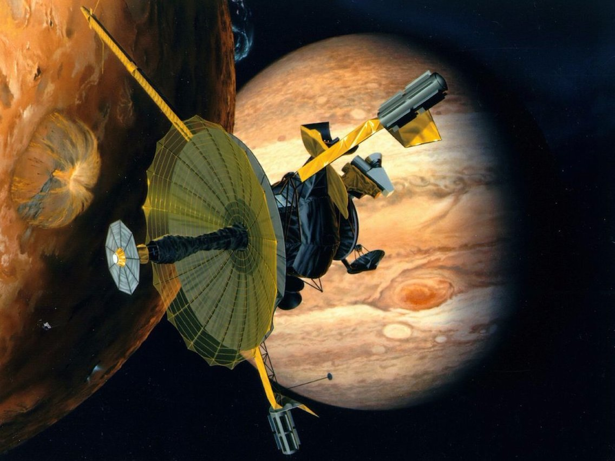

The data came from NASA’s nuclear-powered Galileo probe, which the space agency launched in 1989. The robot reached Jupiter in 1995 and orbited the gas giant and its moons, returning some of the most detailed and astounding data about the distant worlds.

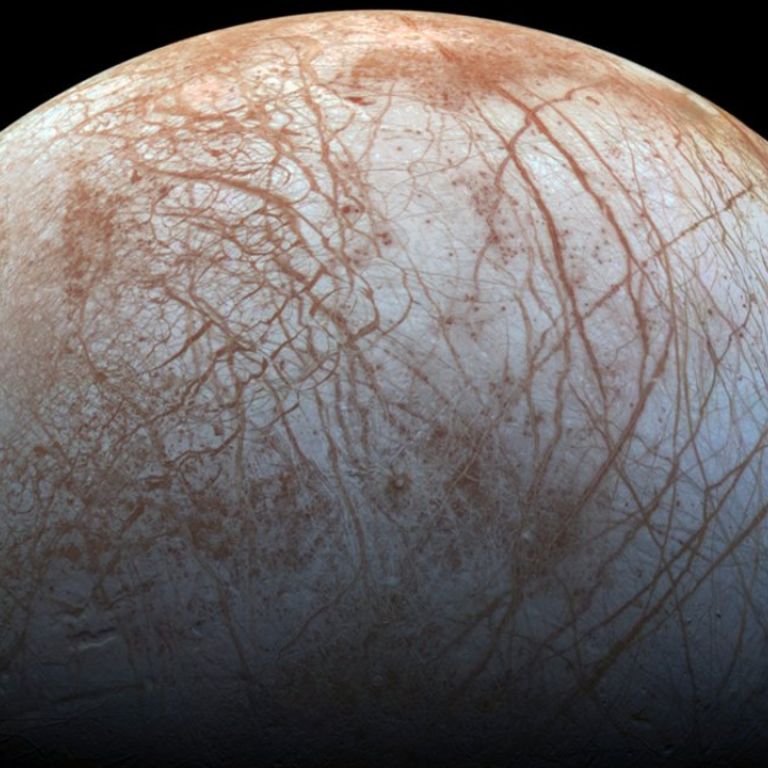

In 1997, Galileo zoomed within 130 miles of the icy surface of Europa, one of Jupiter’s largest moons. Galileo’s magnetic measurements of Europa suggested the moon hides a vast, salty, ocean that harbours more water than exists on Earth.

But the probe never directly encountered any of that water — or so scientists thought at the time.

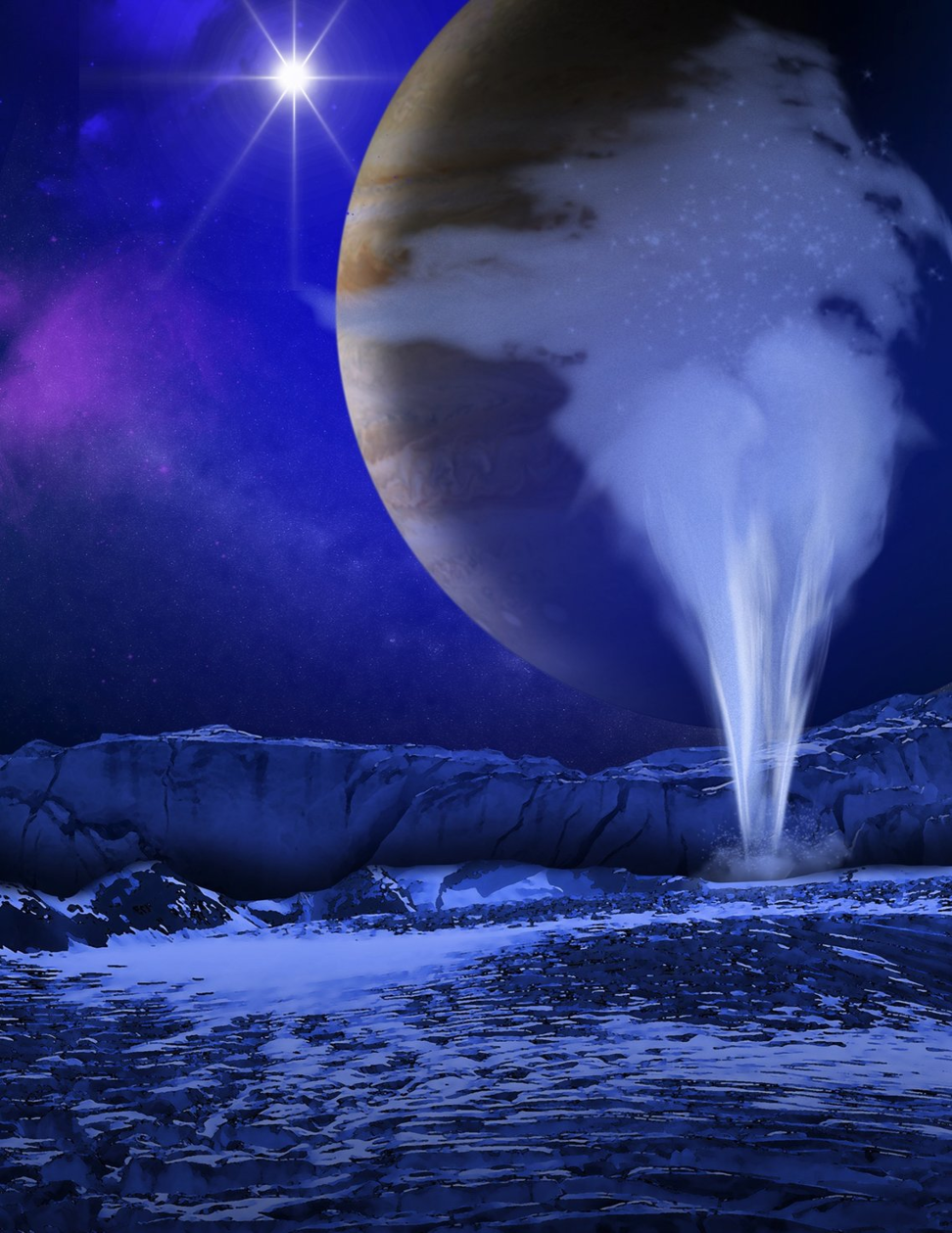

By reanalysing old Galileo data, researchers just discovered that the robot accidentally flew through a giant jet or plume of water sprayed from Europa’s ocean. The team published a study about their work on Monday in the journal Nature Astronomy.

“If this new interpretation is correct, it seems likely that Europa has frequent plume eruptions, and we may see more plumes in the coming years,” Steve Vance, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who wasn’t involved in the study, told Business Insider in an email.

The implications could be enormous. Researchers who study icy moons like Europa think two new missions that will fly by the world — one by the European Space Agency and another by NASA — could “sniff and taste” such plumes as they zoom through them once again.

This could help scientists to determine if Europa’s ocean is habitable to life — or detect signs of it directly — without having to land a probe on the moon’s surface.

A fresh discovery decades in the making

Planetary scientists think there’s a good chance Europa’s hidden ocean might be habitable to alien life. Nutrients sprayed onto the ice by the nearby volcanic moon Io, the thinking goes, may sink down to the ocean floor and serve as food. Meanwhile, hydrothermal vents that blast out hot water could make environments cosy enough to support deep-ocean life (as they did and still do on Earth).

Researchers have long suspected that Europa sprays plumes of water into space — as Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus does — and provide a shortcut to testing these ideas. But until now, solid evidence has been hard to come by.

The best data previously came from the Hubble Space Telescope, which photographed Europa passing in front of Jupiter in 2012 and 2014. Images of Europa’s silhouette cast against the bright clouds of Jupiter showed what looked like water plumes shooting 125 miles into space.

While Hubble’s measurements “were made at the limit of sensitivity” for the telescope, casting doubt on their reliability, the authors of Monday’s study said, they nonetheless inspired the team to reassess Galileo’s 20-year-old data.

Margaret Kivelson was a project scientist during the Galileo mission and is an author of the new study. As a space physicist, she’d used the probe’s 11 flybys of Europa to take detailed magnetic readings, which ultimately helped her prove the moon’s subsurface ocean exists.

But the closest flyby in 1997 created data that perplexed Kivelson and others on Galileo’s science team.

“There were some strange signatures in the magnetic field that we had never really been able to account for,” Kivelson, who now works at the University of California, Los Angeles, said Monday on NASA TV.

The recent Hubble data gave Kivelson and others the idea that a water plume might be responsible, since the spacecraft had passed close enough to Europa to possibly fly through one. So the team reanalysed Galileo’s magnetic data with modern computers and techniques, including a simulation by Zianzhe Jia, a space scientist at the University of Michigan, of what a plume would do to Galileo’s instruments.

“When he ran this simulation, it agreed just beautifully with the data that we had collected” in 1997, Kivelson said.

Their discovery not only suggests Europa’s watery plumes really do exist, but are also frequent and widespread.

“If we find active plumes, then we can sail on through them and sniff and taste that stuff that’s in the plume,” Bob Pappalardo, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who wasn’t a study author, said on NASA TV. “We can analyse the particles and the gases to get a detailed composition of Europa’s interior.”

The two probes on track to ‘sniff and taste’ Europa’s water plumes

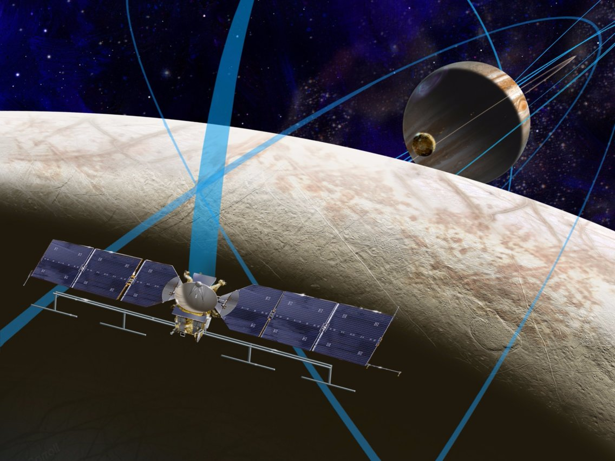

The recent discovery is very good news for two upcoming, multi-billion-dollar missions to Jupiter and its moons.

The European Space Agency’s spacecraft, called the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE), is scheduled to launch in 2022 and reach Jupiter in 2030. That mission calls for two flybys of Europa from about 200 miles away.

The other mission is NASA’s roughly US$2 billion Europa Clipper probe, which may launch sometime between 2022 and 2025 and arrive about half a decade later.

But the Europa Clipper will make 47 flybys and come within 20 miles of the moon’s surface. That would give it unprecedented access to visuals of plumes and the ability to taste of their water for salts, organic compounds, and other chemicals.

“The ... instruments are designed with Europa’s plumes in mind, allowing us to infer the oceans composition and thus its suitability for life, and even to look for direct chemical signs of extant life,” Vance said of the Europa Clipper mission.

Pappalardo previously told Business Insider that oceans on moons like Europa “may be the most common habitats for life that exist in the universe.”

He added: “If there’s life at Europa, it’d almost certainly be an independently evolved form of life. Would it use DNA or RNA? Would it use the same chemistry to store and use energy? Discovering extraterrestrial life would revolutionise our understanding of biology.”