How toilet paper-sharing is a warning sign that China’s start-up fervour is overheating

Awash with money, Chinese venture capital funds chased marginal ideas, leading to a boom-and-bust cycle still playing out in the sharing economy

As an analyst covering tech start-ups in China, Zhao Ziming has seen some really wacky ideas cross his desk. Even so, he was surprised by his cousin, who was preparing to launch a start-up to share rolls of toilet paper.

“My cousin said he always cannot find toilet paper in the restrooms in most office buildings in China, so he is going to start an app to share toilet paper, at one yuan for a roll,” said Zhao, who works for Beijing-based consultancy Cyzone. “I told him that was a really stupid idea and brought him to some restrooms in Beijing to prove that his idea can’t work, that there’s no demand for sharing toilet paper.”

China has seen an entrepreneurial fever sweep the population, lured by tales of exponential riches made seemingly overnight and news about a new class of billionaires minted by the internet boom. Venture capital funds were awash with money and chased marginal ideas, leading to a boom-and-bust cycle that is now still playing out particularly in the so-called sharing economy, which is a term for owners renting out something they are not using.

Reminiscent of the dotcom boom in the late 1990s when any company that added a .com suffix

guaranteed investor interest, many start-ups in China have raised millions of dollars by shopping around concepts tied to sharing. Except that start-up founders and the venture capital money funding them have moved on from cars and homes, represented by the likes of Uber and Airbnb, to areas like rental of bicycles, power banks and even life-size companion dolls.

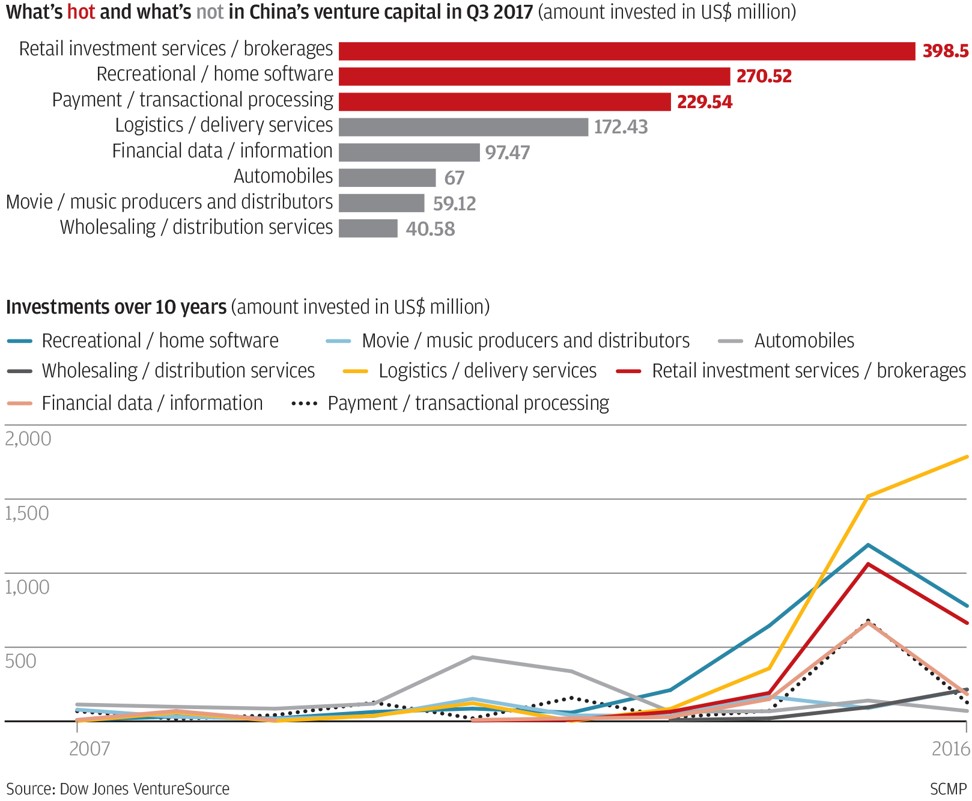

China-based companies raised a total of US$8.8 billion in the quarter ended September, or about half of the US$16.8 billion raised in the same period two years earlier, according to data compiled by Dow Jones VentureSource.

The biggest proportion of that money – 42 per cent – was invested in consumer services, a broad category that covers everything from bicycle sharing and second-hand car trading to online learning. Fintech, shorthand for computer programs that support banking and financial services, was second with about 32 per cent of the investment.

Other reports put the amount of funds raised by sharing start-ups at about US$24.4 billion in the first seven months of this year, about enough to fund two new US aircraft carriers.

Among the most prominent sectors attracting institutional investment is bicycle sharing, which has been popularly referred to as one of China’s four modern-day “inventions” together with high-speed railway, mobile payments and online shopping. The reference itself is a nod to ancient China’s role in the making of paper, gunpowder, printing and the compass.

At its peak, there were about 100 companies offering similar dockless short-term bicycle rental services in China. The market was so crowded – not to mention pedestrian walkways outside subway stations and major tourist attractions – with multi-hued bicycles that those late to the game ran out of colours to paint their bikes. These days, only three companies, Mobike, Ofo and Hellobike, are seen to have enough scale and financial muscle to potentially survive another price war.

The casualties aren’t restricted to bicycle sharing. Beijing-based car-sharing companies Ezzy and Youyou, as well as umbrella-sharing company Huoli Modeng and sleeping-capsule sharing enterprise Xiangshui Space all announced they had ceased business operations this year.

These start-ups typically failed because they had run out of funds before being able to find a sustainable profitmaking model. Many times, these companies had to effectively give out their products and services for next to nothing in the hopes of building a sizeable user base that they could then either charge a fee (once the other competitors all died off) or sell the data to some third-party user to mine for marketing and sales leads.

With the era of fast-and-easy money largely over, venture capital investors like Andrew Yanyan are becoming more selective.

“I have become humbler and more cautious in selecting investment projects and entrepreneurs over time because of my experience of failure,” said Yanyan, who has been in the venture capital industry for over 20 years and is founding managing partner of SAIF Partners.

Separating good ideas from bad is easy compared with identifying a good start-up founder, which is arguably a more important determinant of the company’s eventual success, he said. “But I myself get confused about what makes a good start-up founder.”

For Zhao at Cyzone, the current fever for all things artificial intelligence, spurred on by high-profile backing by the central government, is a harbinger of a bust to come.

“The golden time of attracting investments only by ideas has passed,” said Zhao.

“Now people and capital are shifting their attention to artificial intelligence and machine learning. In the coming two years, closures will increase in these sectors.”