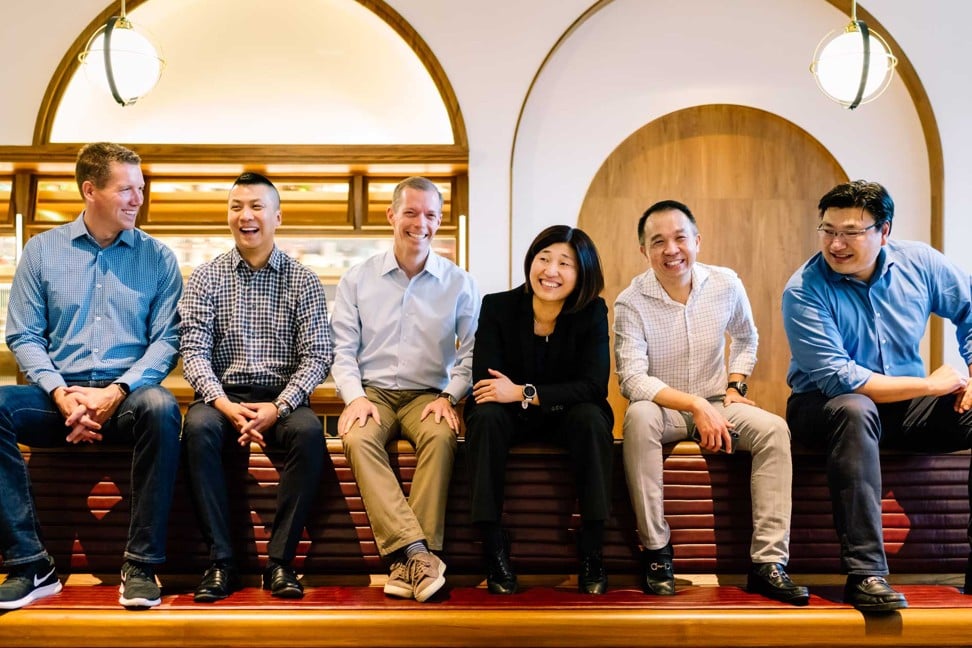

Women in tech: GGV Capital’s Jenny Lee reflects on investing in China’s technology market

- Her work as a venture capitalist in China sometimes involve being a psychiatrist or even a marriage counsellor

Jenny Lee, a managing partner at private equity firm GGV Capital, says being a venture capitalist (VC) in China can veer from analysing companies and deals to being a psychiatrist or even a marriage counsellor when needed.

Based in Shanghai, Lee said in an interview that she once had to call up a start-up founder’s wife, who thought her husband was neglecting their family, to explain that the man frequently slept at the office because he was working hard to raise a new round of financing to keep their company afloat.

“Sometimes female investors are more emotional and sensitive than male investors,” Lee said. Still, she considers that trait as a strength because “VC [deal making] is a people business”.

Such insights have served Lee well since 2005, when she established Menlo Park, California-based GGV’s first office in China. At GGV, she has been instrumental in investing and helping eight early stage start-ups go public on the New York and Hong Kong stock exchanges as well as on the Nasdaq-style ChiNext board of the Shenzhen Stock Exchange.

China’s venture capital firms outperform US, European peers amid breakneck economic growth in the past two decades

Lee, 47, is widely considered to be one of the most respected VC investors in the world’s second largest economy, according to the 2019 Midas List, the annual ranking of the world’s top tech investors published by Forbes magazine in partnership with TrueBridge Capital Partners.

She first made the Midas List in 2012, ranked at No 94, and cracked its upper echelon in 2015 when she took the No 10 spot, which was the highest ever ranking for a female VC at that time. This year, she was ranked No 19.

“A lot of my investment decisions derive from my life,” said the Singapore-born Lee, who credits her deep understanding of China’s tech market to being constantly curious and open to new information.

Her decision to invest in Tangdou, operator of a social media app that teaches elderly people how to dance, was based on her observation of middled-aged Chinese men and women dancing for hours at a public square.

Tencent eyes silver generation with investment in video app for dancing grannies

Tangdou, which means “jelly bean” in English, was launched in 2015 as a dancing video app by Beijing-based Xiaotang Technology. It features tutorials that break down the choreography for a variety of dance styles including Chinese folk dance, jazz, ballroom and even hip-hop.

Lee, however, also admits to missed opportunities, which have provided valuable lessons about China’s tech sector.

The GGV team in China knew about ByteDance founder Zhang Yiming and his project, news app Jinri Toutiao, very early on, but decided not to pull the trigger and invest in the start-up.

“We thought advertising-driven businesses had short ceilings in China,” Lee said. “We were wrong.”

GGV Capital raises US$1.88 billion to invest in US and Chinese start-ups

GGV swapped its shares in lip-synching karaoke app Musical.ly to ByteDance when the TikTok operator acquired the Shanghai-based company in November 2017. ByteDance merged Musical.ly with TikTok in August last year. ByteDance became the world’s most valuable start-up after it received an estimated US$76 billion valuation during its latest funding round in October last year, backed by investors such as SoftBank Group Corp.

GGV has secured US$1.88 billion in new financing, one of the largest global fundraising efforts last year, that allows it to manage 13 funds worth US$6.2 billion, focusing on both China and US investments. The firm has sharpened its coverage on four sectors – consumer new retail, internet services and social networking, business and cloud services, and cutting-edge technology.

Lee said she first aspired to become a VC after taking an entrepreneurship course at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, where she earned Master’s and bachelor’s degrees in electrical engineering.

Following graduation, Lee returned to Singapore and worked for four years at STE Aerospace, where she served as an engineer retrofitting fighter jets.

She later went back to the US to get her Master of Business Administration degree from the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University. In 2001, she moved to Hong Kong to work at Morgan Stanley. The following year, she took a job at Japanese VC firm JAFCO Asia where she cut her teeth in investments before joining GGV as a managing partner in 2005.

“You need to understand technology and finance – and [have] an MBA, too – to be a good tech investor,” Lee said.

Still, there have been barriers to overcome in terms of diversity in the VC community.

When the VC industry initially developed in the US, it started from family businesses where the focus was on industrial investments, according to Lee. She said things later shifted to Ivy League schools, such as Harvard University and Yale University, where fellow MBA holders teamed up to pursue deals.

“It was hard to start up a firm, so people tended to find people they were already acquainted with to be partners,” Lee said. “Their resumes look almost the same.”

China’s gig economy attracting more women as they seek financial independence amid slowing economy

Only 11 per cent of decision-makers at US-based VC firms, with a portfolio valued at more than US$25 million, are women and 71 per cent of VC firms in the US have zero women investors, according to data from VC group All Raise. As a result, it estimated that only 12 per cent of US VC funding in 2018 went to start-ups with at least one female founder.

At GGV, there is considerably more diversity, with two out of four presidents being female. Lee said the firm did not set out to have that ratio because it recruited people who most fit the work, regardless of their gender. For example, a good investor in the consumer sector would be a retail specialist, according to Lee.

“I can see more women investors and entrepreneurs in China than the US,” she said.