Hong Kong start-up behind protest crowd-counting using AI to estimate subway wait times, detect gas leaks

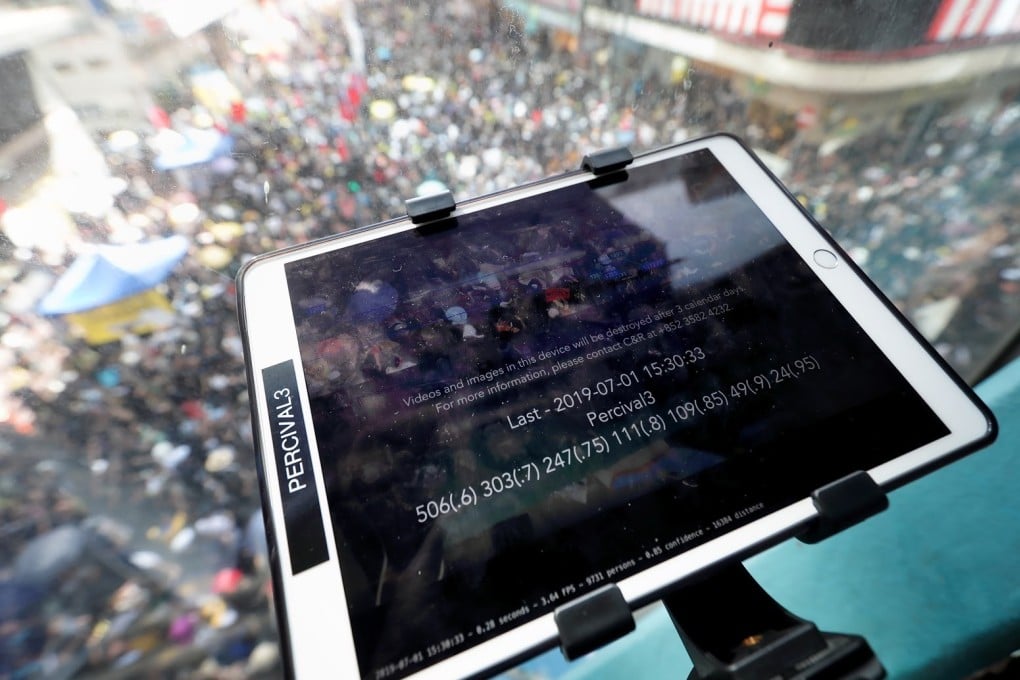

- Wong’s project concluded that 265,000 people joined the protest on July 1, while organisers said 550,000 people marched and the police estimated it was 190,000

C&R Wise AI, the Hong Kong start-up that provided artificial intelligence technology to accurately count the number of street protesters in the city, is also helping universities and railway operators better manage their crowds as private businesses and the government in the former British colony step up their use of AI.

City University of Hong Kong is deploying the company’s EdgeAI system, which runs algorithms on an industrial computer to process images of people and objects, to count the number of students and teachers on campus to provide insights into crowd flow at major entrances and exits, according to Raymond Wong, founder and managing director of C&R Wise AI.

The technology is used in the city’s subway stations to provide an estimate of passenger waiting times during peak hours, while local gas companies deploy the AI system to detect entries to remote sites as well as leaks or rust on gas pipes that need repair.

Wong, a graduate of the University of Hong Kong with a bachelor and master’s degree in computer engineering and computer science, started C&R in 2009 as a software development firm for public organisations and international brands, but soon saw the increasing potential in the application of AI. He started the AI branch two years ago to focus on using perception-based AI technology to help businesses detect people and various objects.

The focus on C&R Wise comes amid the city’s increasing adoption of AI in businesses and public organisations as the government continues to encourage innovation and build a world-class smart city in mobility, living, environment, public service and other fields.

C&R’s crowd counting technology came into the public spotlight after the annual July 1 protest march in Hong Kong. Teaming up with Paul Yip, social sciences professor at Hong Kong University, and Edwin Chow, a geography researcher from Texas State University, Wong and his team set up three iPad cameras on Percival Street in Causeway Bay and four more on Arsenal Street in Wan Chai.