As demand for genetic testing grows in China, start-up 23Mofang can now tell if you have royal blood

- Test results include ancestral information, hereditary disease risks and traits like alcohol tolerance level

- China’s direct-to-consumer genetic testing market is predicted to reach US$4.3 billion by 2023

It is a tantalising promise: for 449 yuan (US$64) and a saliva sample, Chinese genetic testing company 23Mofang can extract your DNA and genotype it to provide a comprehensive report that includes ancestral information, hereditary disease risks and traits like alcohol tolerance level. But what sets 23Mofang apart from other consumer genetic testing providers in the market is that it can determine if you are a descendant of ancient Chinese royalty.

The company, for example, estimated that 1.81 per cent or about 25.3 million of China’s existing population are descendants of Liu Bang, who went on to become Emperor Gaozu of Han – founder of a dynasty that spanned more than four centuries.

“When we first did some market research on whether Chinese consumers wanted to get their genes tested, people thought that it was primarily for paternity tests, to check if their children are biologically theirs,” said Zhou Kun, co-founder and chief executive of 23Mofang, in an interview at the firm’s headquarters in Chengdu, capital of Sichuan province in western China.

“Genetic testing is now starting to get a bit more popular … and users realise that they can benefit by gaining a better understanding of their health and heritage.”

To say that the genetic testing market has grown rapidly over the past decade is an understatement. The costs of direct-to-consumer genetic testing has come down in recent years, and US companies like 23andMe and AncestryDNA offer test kits for as low as US$99.

At the start of this year, an estimated 26 million consumers have taken tests provided by genetic testing providers, according to a report by the MIT Technology Review. It said more people bought tests in 2018 than in all previous years combined.

The low cost of genetic testing has prompted a slew of Chinese companies, including 23Mofang and Shenzhen-based WeGene, to enter the market and tap growing demand in the world’s second largest economy, which is expected to reach US$4.3 billion by 2023. Compared to the US, China remains a fairly nascent market for direct-to-consumer genetic testing.

Founded in 2015, 23Mofang has tested only about 500,000 consumers out of China’s 1.4 billion population. By comparison, 23andMe has about 10 million clients.

Still, Chinese companies like 23Mofang and WeGene are driving efforts to tailor genetic testing for East Asian consumers, which were previously under-represented in the databases of Western genetic testing providers.

AncestryDNA currently breaks down Asian ethnic descent from several geographic markets, including China, Central and Northern Asia, Korea and Japan. Similarly, 23andMe’s breakdown for East Asia include Chinese, Chinese Dai people, Filipino, Japanese and Korean.

That means Chinese individuals who use AncestryDNA genetic testing could simply receive a result that tells they are largely descended from China, which is something they already know.

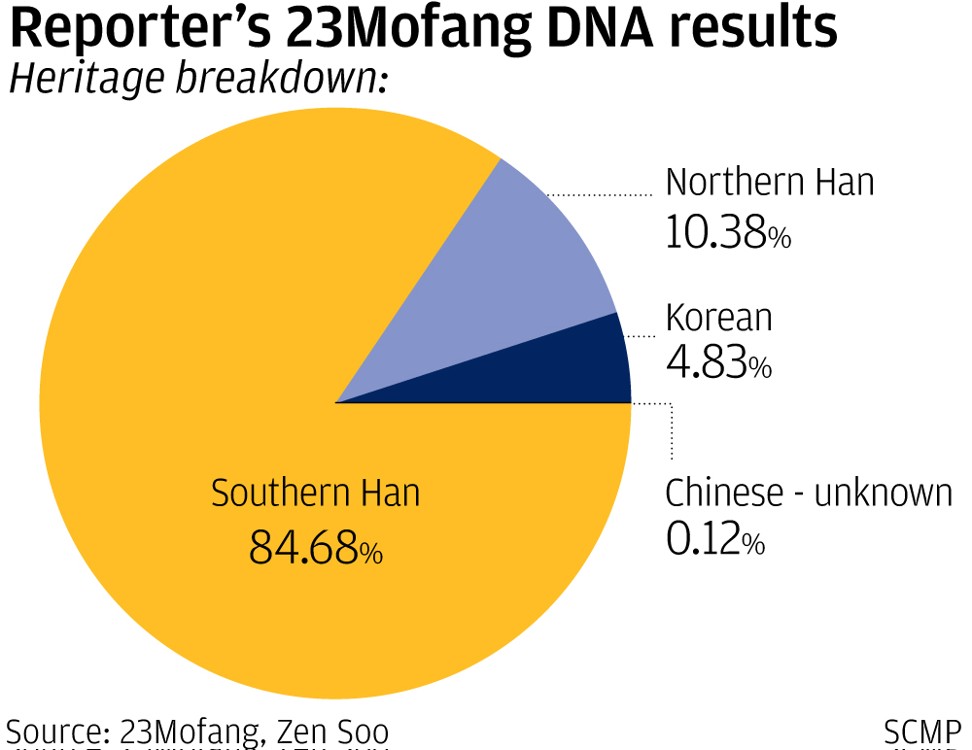

The difference with the databases of genetic testing companies like 23Mofang is that these consist largely of East Asian and Chinese users. These firms are able to break down ethnicity even further into subgroups, determining whether a Chinese person is Northern or Southern Han, or part of minority ethnic groups such as Miao, Zhuang and Dai, or Uygur.

“Previously, there were these funny reports of Chinese who took these genetic testing kits, only to find that the results would come back informing them that they are indeed Chinese,” said 23Mofang’s Zhou. “It’s a joke, right? I mean, just based on how I look, I know I’m Chinese. I wouldn’t need a genetic test to tell me that.”

Who are you? DNA tests help Chinese retrace ancient steps

“In China, people want to go a layer deeper and find out what ethnicity they are exactly,” Zhou said. “It’s different from the US, which is a country of immigrants where people want to find out which European countries their ancestors came from.”

He indicated that genetic testing users in China place more emphasis on retracing their family tree and how family surnames were passed on. These users find it more interesting to know whether they are genetically related to emperors and legendary figures in Chinese history, such as Emperor Gaozu or Song dynasty scholar-official Sima Guang.

For descendants of the first Han emperor, research by the 23Mofang team found nearly a quarter of a specific haplogroup – a genetic population of people with a common ancestor – had a strong association with people surnamed Liu in China.

The company sequenced 70 DNA samples from this haplogroup and determined that these users shared a paternal ancestor from more than 2,000 years ago, which was roughly the time when Liu Bang’s father, Liu Tuan, was born.

That genetic testing also confirmed that over the next 300 years, there were occasions where the haplogroup expanded in population, which corresponded to the reigns of subsequent emperors who would father multiple sons, many of whom spread the Liu family name.

As such, 23Mofang was able to conclude with confidence via genetic testing whether an individual is a descendant of the Han dynasty’s founder.

23Mofang also offers a variety of tests that purport to determine if you are more inclined to altruism, whether you work well under pressure and even how your skin could be acne-prone. Those are in addition to tests that can predict one’s vulnerability to diseases such as diabetes, glaucoma and arthritis.

“With genetic testing we’re not trying to diagnose users,” Zhou said. “We simply provide a guideline on how users can live a better life or make lifestyle changes to reduce risks [from hereditary illnesses].”

In future, Zhou said life can be digitised and computed with the aid of genetic testing, which would provide opportunities in everything from disease prediction to medical research. 23Mofang, however, is not yet focused on working with hospitals and medical institutes and is still at the stage of building a more comprehensive database, he said.

At this early stage of the genetic testing industry, the goal for 23Mofang is to compile a database of 50 million people. This effort will require Chinese consumers to learn more about how genetic testing can help improve their lives, according to Zhou.

Most of 23Mofang’s users currently come from the large Chinese cities and tend to be well-educated white-collar workers, who also buy genetic testing for their families.

“I believe that it’s always better when humans try to understand themselves more … to help gain a better quality of life,” Zhou said.

While genetic tests provide a wealth of information to users, there are many tests which should only be taken with a pinch of salt, according to Zheng Chaogu, an assistant professor at the University of Hong Kong, who specialises in the fields of neuroscience and genetics.

To be sure, many of the scientific papers that have found correlations between a specific gene and traits, which have helped form the basis of 23Mofang’s genetic testing results, are not conclusive studies.

On determining whether one is of Northern or Southern Han ethnicity, 23Mofang based its conclusions on a study of 1,700 Chinese people from 26 provinces. That study excluded large metropolises like Beijing and Shanghai because such cities tend to have a large number of immigrants from other regions.

“So for such studies, there are assumptions made, and you have to buy into those assumptions [if you believe the results to be true],” the University of Hong Kong’s Zheng said. “The sampling of Chinese people is limited in the study, less than 2,000 people [compared to the total population of 1.4 billion]. To get really good coverage, you need millions of people … for statistical power to discern the differences between Northern and Southern Han.”

What one Hong Kong writer found out when she had her genes sequenced

For “fun” tests that can tell whether an individual has the gene for altruism, Zheng indicated that the results were based on a German study, which took cheek swabs from participants and then surveyed their willingness to donate money.

The study found that a mini-mutation of the so-called COMT gene could affect how altruistic people become, with certain variations leading some survey participants to donate twice as much as others. This study was termed “explorative” by the authors, and did not control for factors such as the economic backgrounds of participants.

“So from a scientific point of view, many of these studies are a first step for a deeper study to find a bunch of candidate genes that may be related to this particular problem,” Zheng said. “But unless you can kind of recreate the mutation in the animal model to confirm that the mutation can cause this problem, you can’t make a definitive conclusion.”

The kinds of genetic tests that produce solid results in consumer genetic tests today are largely the same ones that are already used in hospitals, such as lactose intolerance and blood type, and whether one has phenylketonuria (PKU) – a rare disorder where one’s body is unable to break down a substance called phenylalanine, found in proteins and some artificial sweeteners like aspartame. Tests for PKU are typically administered to infants right after birth.

“These are very well-established tests,” Zheng said. “Regular hospitals already do this, so you don’t necessarily have to do a genetic test to find out.”

In China, people want to go a layer deeper and find out what ethnicity they are exactly

As demand for direct-to-consumer genetic testing has grown in China, so have privacy concerns. Since DNA essentially makes up a person’s biological identity, giving private companies that data in exchange for some interesting information about genetic traits is considered a massive trade-off.

“In exchange for your DNA they give you several hundred test results, but you won’t know if they’re testing your DNA for your entire genome or doing all kinds of association studies in the background,” Zheng said. “You don’t know what they could be doing with your sample, and the scary part is that … without regulation, they can do many things that could constitute an invasion of privacy.”

Zheng also indicated that these providers are currently not making money, based on the low prices of the genetic testing kits in the market. “They’re bleeding money in exchange for building their databases,” he said.

Why DNA testing kit makers are investing in China

He urged all persons interested in genetic testing to first read the terms of service from the provider to ensure they know how their genetic information will be used. “It’s like any sort of trade-off,” he said. “If you want to do the test to know what’s wrong with you or improve your life, part of your privacy has to be given up.”

The terms of service from 23Mofang, for example, indicates that the genetic information collected will be used for further scientific research if users agree to take part in other studies. It emphasised that the company will not disclose any personal information to third parties without user consent, with the exception being to comply with certain laws and regulations, or judicial systems in the country. It also offers users the option for their biological sample to be destroyed at any time, instead of being kept in storage.

Zheng said consumers must also consider the privacy of others when they decide to do genetic testing because their DNA can reveal those of their entire family. “Everyone should think of DNA as their data,” he said. “It’s very valuable. It’s basically your identity that you’re giving out to a company.”

Illustration: Henry Wong

For more insights into China tech, sign up for our tech newsletters, subscribe to our Inside China Tech podcast, and download the comprehensive 2019 China Internet Report. Also roam China Tech City, an award-winning interactive digital map at our sister site Abacus.