A brutal price war is ravaging couriers in China’s live-streaming e-commerce hub, where not even SF Express is spared

- Indonesia’s J&T Express was punished by Yiwu’s municipal postal authority for dropping delivery prices to 15 US cents per parcel

- The resulting price competition has hammered couriers trying to keep up with demand from the many e-commerce shops in the city, known for its cheap goods

In a village 250 kilometres (150 miles) southwest of Shanghai, along a street peppered with rickshaws of various colours and flanked by five-storey buildings brimming with goods, mountains of boxes sit waiting for the myriad delivery workers who have to handle them, keeping the couriers from wading through the hundreds of matchbox-sized shops in the area to find everything they need to collect.

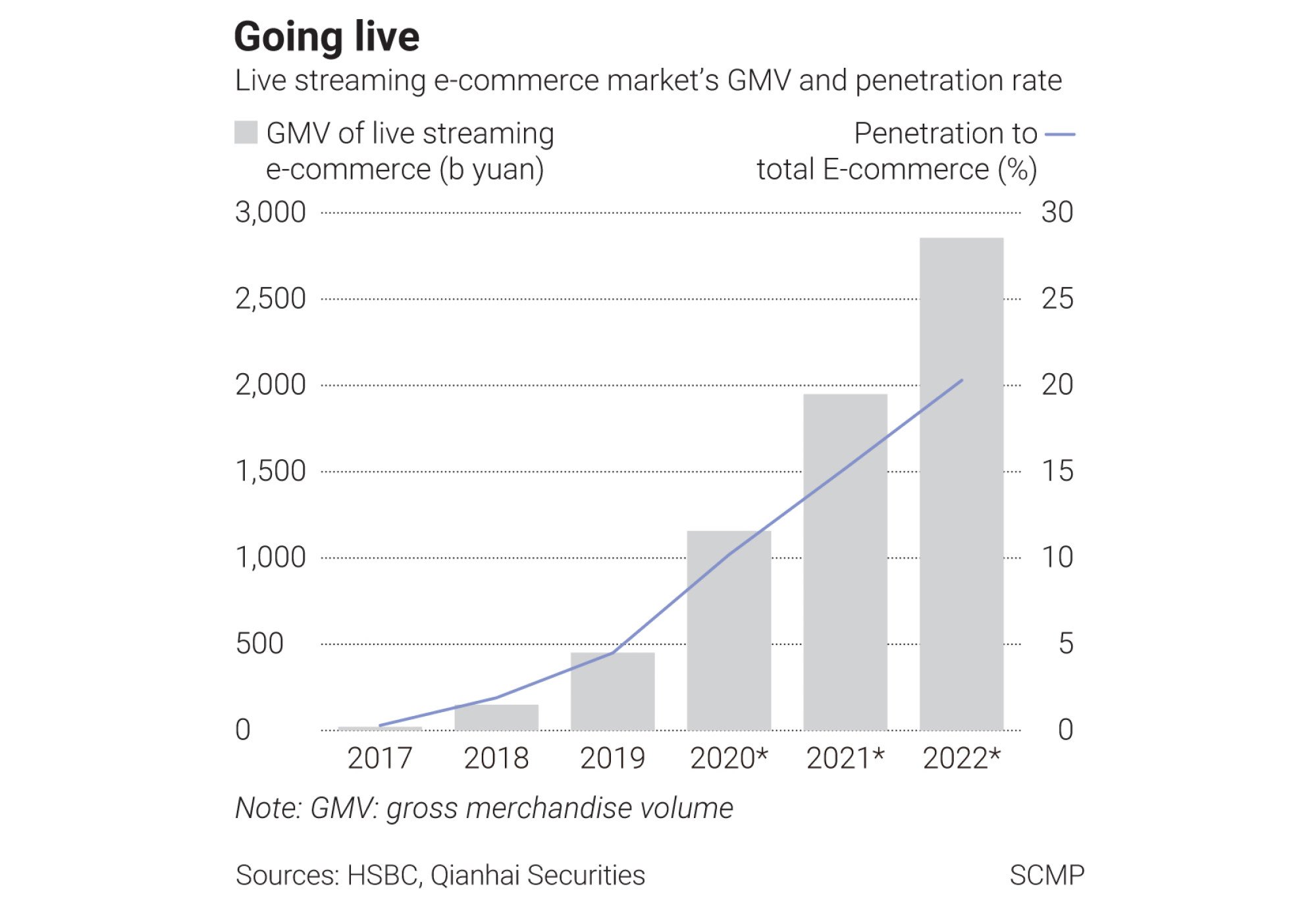

The massive logistics flow in Beixiazhu is a result of the village’s booming live-streaming e-commerce industry. Located in Yiwu, a manufacturing hub known for cheap wares such as socks and much of the world’s Christmas decorations, Beixiazhu has become the go-to place for enterprising live-streamers to hawk an endless supply of local products online in the age of Covid-19.

This has also made it the site of China’s most vicious price war among delivery companies after a new market entrant, Jakarta-based J&T Express, offered its services for as little as under 1 yuan (15 US cents) per package, raising government scrutiny and keeping China’s largest private courier, SF Express, at bay, according to interviews with dozens of merchants and delivery crews in the area.

“The price war is intensifying – express delivery companies are locking horns and revenue from single-package [deliveries] is still declining,” said Dai Mingzhe, an analyst at research firm LeadLeo. “It is still difficult to predict the turning point of the price war in the short term, and it is possible for the single-package price to further decline.”

The area’s massive output has created economies of scale that make delivery service charges in Yiwu among the lowest in China. The scale of commerce also attracted J&T Express, armed with investment from the likes of Hillhouse Capital, Sequoia Capital and Boyu Capital, which has driven down bulk order pricing to the point of drawing ire from other companies.

J&T, whose Chinese name Jitu means “speedy rabbit”, was founded in 2015 by entrepreneurs Jet Lee and Tony Chen, former CEO of Oppo Indonesia and founder of the smartphone brand, respectively. When the company started competing in Yiwu, it precipitated a price war with prices as low as 0.9 yuan to deliver a package hundreds of miles away. Competitors were forced to respond by dropping their prices, which eventually caught the attention of the Yiwu municipal postal authority.

Last week, the authority ordered J&T to shut down some production lines in its delivery centres and raise its prices. The delivery spots in Yiwu, marked by the company’s bright red logo with white letters, were still operating on Sunday along the busy street where boxes were collated using motorised rickshaws.

Delivery workers nearby said J&T’s lowest price was now up to 1.4 yuan per parcel for merchants that guarantee 1,000 parcels per day. This was just slightly higher than the 1.3 yuan price the company had just before the government intervened, a change that workers say happened because the market could not sustain the cut-throat pricing long term.

The new pricing still undercut the competition, though. Other players such as ZTO Express and STO Express were charging 1.5 yuan under the same conditions, which is about a third less than the nationwide average and is likely not enough to cover costs.

Shu Xi, who runs a 30-person team selling lighters from Yiwu, where he has lived for more than a decade, said that delivery prices have gradually declined since 2016. “From 6 yuan to 5 yuan, then further declines to 4, 3, 2, 1 yuan,” he said, “J&T Express is still the cheapest one.”

J&T did not respond to multiple interview requests.

The competition in Yiwu is a sign of a broader trend in China that some have referred to as economic involution, or slowing growth amid the rapid development of new market segments. The result is a bruising fight for market dominance that eventually forces consolidation, resulting in an oligopoly controlled by the few survivors.

LeadLeo’s Dai said J&T Express is a typical “catfish” in the market, which causes other players to follow its lead.

“After just a few years of rapid development, the company’s valuation has surpassed [some of those market leaders],” he said. “However, the express logistics industry is an asset-heavy industry, after all, and it can only go through further large-scale capital expenditures and improved management efficiency.”

Chinese courier giant’s US$12 billion stock wipeout sends a warning to traders

Delivery firms are sacrificing short-term profits in the hope of pricing out competitors, according to Dai, but “such vicious competition is unsustainable, and this phenomenon may not be alleviated until the market concentration rises to a certain level.”

While the delivery service price war is particularly intense in Yiwu, the trend is visible nationwide. China handled 83.6 billion express delivery orders last year, a 31.2 per cent increase over 2019, according to data compiled by China’s State Post Bureau. Total revenues were only 17.3 per cent higher last year, though, showing unit prices continued to fall.

The per unit price from Yunda Express, one of China’s largest delivery services by volume, fell 30 per cent, while STO’s declined 23.7 per cent.

While China’s express delivery industry supports many smaller players, and more than 3 million workers, 80 per cent of it is controlled by just eight companies, which include Yunda Express, STO Express, YTO Express and SF Express.

As China’s largest courier, SF charges an average of 17 yuan per delivery, while others charge closer to 2.5 yuan. As a result, SF has more than three times the revenue of its nearest competitor.

SF Holding, the owner of SF Express, reported 154 billion yuan in revenue in 2020, a year-on-year increase of 37 per cent. By comparison, Yunda Express had 32 billion yuan in revenue last year. YTO Express pulled in 29 billion yuan and STO Express made 21 billion yuan.

But SF Holding, which reported a profit of 907.3 million yuan in the first quarter last year, shocked the market last Thursday when it said it expected a net loss of between 900 million yuan and 1.1 billion yuan in the first quarter of 2021. The company’s share price plummeted 20 per cent in the three trading days after the announcement, piling onto a decline that has seen the stock shed nearly half of its peak value from mid-February.

To stem some of the bleeding, delivery service providers are cozying up with some of the biggest names in e-commerce.

YTO, STO, ZTO and Yunda all have backing from Alibaba. This has given the e-commerce giant a foot in an industry that competitor JD.com entered directly by building out its own delivery force under JD Logistics, which is expected to float shares in Hong Kong soon.

J&T Express, which has 350,000 employees globally, is considering a US initial public offering that could raise more than US$1 billion, Bloomberg reported this month, citing unnamed sources. Its rapid expansion in China has fanned rumours about the company having a deal with e-commerce platform Pinduoduo, which now boasts more active online buyers than Alibaba.

Addressing potential competition from livestreaming, Alibaba’s chief executive Daniel Zhang described the trend as “more like event marketing, as part of [an] entire operation, [that] is impossible to do seven days, 24 hours.”

“If you look at the details of livestreaming today, most merchants view it as a way to do promotion and acquire new customers, but they do need a sustainable and day-to-day operation platform, which is the Alibaba platform,” he said during an earnings call last year. “That is why a lot of merchants build their stores from our platform and they are trying to bring all their consumers and customers from different ways to Taobao, because this gives them the best way to operate, as well as the highest returns on their investments.”

After J&T Express was disciplined by Yiwu authorities, Pinduoduo told merchants in a notice last week that it had no special relationship with the delivery firm. Instead, it punished J&T by raising its deposit requirement for allegedly misleading merchants by suggesting its service would allow them to avoid certain regulations on the platform.

Despite this recent tension, the two firms are actually following similar strategies, according to iiMedia Research CEO Zhang Yi.

“If J&T Express wants to win the market … it has to offer a price cheaper than anyone else, and this won’t be a short term thing,” Zhang said. “Just like the low price strategy offered by Pinduoduo, [companies need to] grit their teeth and keep going.”

The price war is also the main reason for SF’s losses, Zhang added.

For merchants in Beixiazhu, this is obvious. Hardly a single SF Express vehicle can be seen on the local streets. Its average price is higher than what is preferred on e-commerce platforms, which often advertise shipping prices of “9.9 yuan to your door”, be it a T-shirt, a pair of socks, a toothbrush, a mug, or even a potted plant.

Many of the merchants said they have not seen an express delivery price of more than two yuan for small parcels in a long time. For now, that pricing pressure does not appear to be letting up, even after the local government stepped in.

“In my memory, the express delivery fee [in Yiwu] is lower than any other place,” said Zheng Liuping, a 36-year-old live-streamer living in the city.