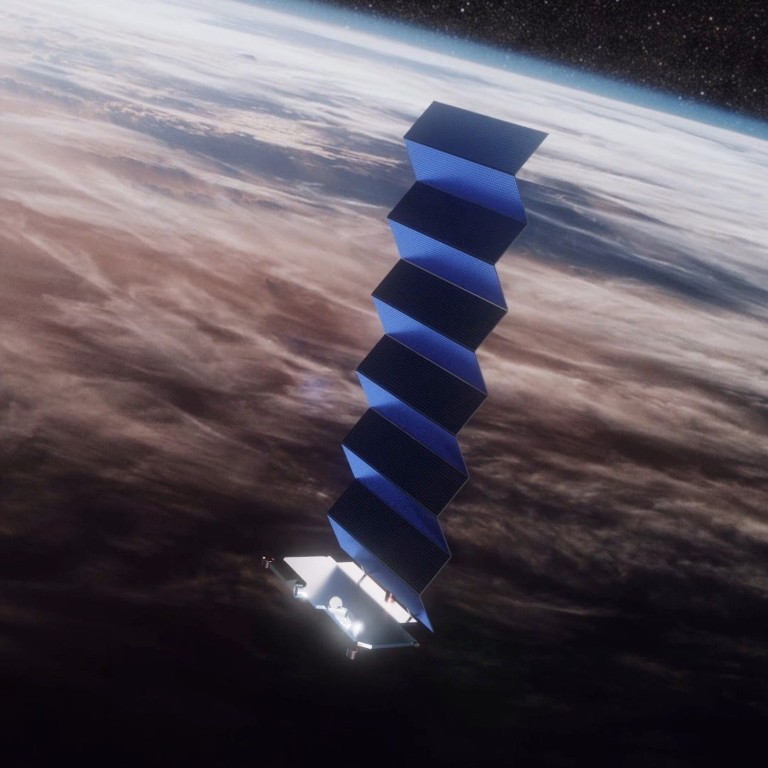

To compete with Elon Musk’s Starlink, China’s private space ventures must work with their state-owned competitors

- In an effort to catch up with Elon Musk’s Starlink satellite internet, China established a new state-owned group to coordinate industry resources

- Private rocket and satellite makers bring innovation to China’s state-led space efforts, but they also face competition from state-owned giants

He and his colleagues were inspired by Google’s Lunar X Prize, a competition for privately funded teams to be the first to land a lunar rover on the Moon. Since paying a state-run company to launch the rover would have been too expensive – and there were no private options – they had to give up before they could even start.

“I felt like someone in China must start this, even though at the time it still wasn’t recognised by most people, and there weren’t clear policies,” said Xie, founder and CEO of Chinese commercial satellite start-up Commsat. “By the time we realised it was the right time, it might have been too late.”

Two such companies – China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) and China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC) – have been planning their own constellations named Hongyan, Hongyun and Xingyun. The three projects combined plan to launch more than 500 satellites into low-Earth orbit.

Despite being just a few months old, China SatNet ranks 26th on an official list of 96 state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Some analysts interpret the list as a ranking of the importance Beijing places on the firms, with the top mostly populated with military- and infrastructure-related companies.

China SatNet comes in right after the country‘s three major telecoms providers: China Telecom, China Unicom and China Mobile. Analysts say this suggests China SatNet could operate as the country’s fourth telecoms provider and help spur the development of commercial space firms.

“The founding of SatNet will stimulate the entire space supply chain, because it needs to procure satellites and launch services,” said Lan Tianyi, founder and CEO of Beijing-based space consultancy Ultimate Blue Nebula.

Blaine Curcio, founder of Hong Kong-based Orbital Gateway Consulting, said that while it is unlikely that China’s first big satellite broadband constellation will be run by a private company, such enterprises can still supply the rockets and satellites.

“If China wants to launch thousands or tens of thousands of satellites, they need a lot of rockets,” said Curcio. “A lot of CASC’s future rockets are spoken for. They have missions, including to Mars and China’s space station, so private rocket companies can contribute.”

Commercial space companies started to appear in China in 2014, after the State Council issued a policy paper that encouraged private investment in the sector, which was previously restricted to SOEs. Chinese entrepreneurs, motivated by the success of SpaceX, quickly joined the fray, according to research conducted in 2019 from the Institute for Defense Analyses, a US non-profit organisation that manages government-funded research centres.

In 2020, Chinese private space companies raised more than 10 billion yuan (US$1.5 billion) in funding, up from 1.4 billion yuan four years earlier, according to a June report from Cyzone, a Chinese start-up consultancy. That includes manufacturers of satellites and rockets.

Beijing-based satellite maker Galaxy Space said in November that it is now valued at more than 8 billion yuan after a series B funding round. Commsat’s latest funding round included money from the China Internet Investment Fund, a state-owned fund jointly launched by the country’s internet watchdog Cyberspace Administration of China and the Ministry of Finance. The company would only confirm the undisclosed sum as above 100 million yuan.

Last year, Chinese commercial rocket manufacturers LandSpace and i-Space each raised 1.2 billion yuan from major investors, including Sequoia China and Matrix Partners China.

Commsat’s Xie said that commercial companies can complement SOEs by taking on smaller and more flexible space missions, while the important national missions that must be “absolutely safe” are left to the state-run space giants.

However, private firms still have to compete with SOEs, as both CASC and CASIC already have their own launch capabilities for vehicles and satellites. Private firms are at a disadvantage, as well, as SOEs use their insulation from market pressures to advantage themselves, according to Lincoln Hines, an assistant professor at the US Air War College who researches China’s space capabilities.

“Although it may be in China’s economic interests to increase competition domestically, it is hard to imagine the Chinese Communist Party abandoning its national champions, which have allowed it to accrue prestige with domestic audiences,” Hines wrote in a column for East Asia Forum.

Ultimate Blue Nebula‘s Lan said this means private firms must rely on “new technology and bolder experiments” to compete with the “national team”.

One of these bolder experiments is using liquid methane to fuel rocket launches, which is being developed by some of China’s leading private rocket companies. Liquid methane produces more momentum per unit of fuel, making it less costly than traditional solid fuels. However, it faces technical challenges.

One start-up working on this solution is LandSpace, which hopes to fuel its medium-lift launch vehicle Zhuque-2 with liquid methane, enabling it to carry a 6,000kg (13,228lbs) payload to low-Earth orbit. The company is planning to conduct the rocket’s highly-anticipated first orbital launch this year.

01:03

China launches Long March 2D rocket carrying Beijing-3 and three other satellites

“We’re competing with ourselves,” LandSpace CEO Roger Zhang said at an online conference hosted by the Asia-Pacific Satellite Communications Council last December. “No one in China has ever proved that they can make liquid launchers.”

No liquid methane-powered rockets have yet to make it to orbit, including SpaceX’s booster for its Starship system named Super Heavy, which uses the fuel in a reusable engine called Raptor. SpaceX plans to conduct its first orbital test flight next month, after it reached an altitude of 10km (6.2 miles) earlier this year.

So far, SOEs have preferred to stick with solid propellants, which are more reliable, Lan said.

Even as dozens of private companies, with the help of beneficial government policies and funding, work to build an industrial base in support of China’s satellite internet vision, the industry remains fragmented, according to Orbital Gateway Consulting‘s Curcio.

“It’s still to be decided whether a centralised thing like SatNet can provide the coordinating element,” he said.