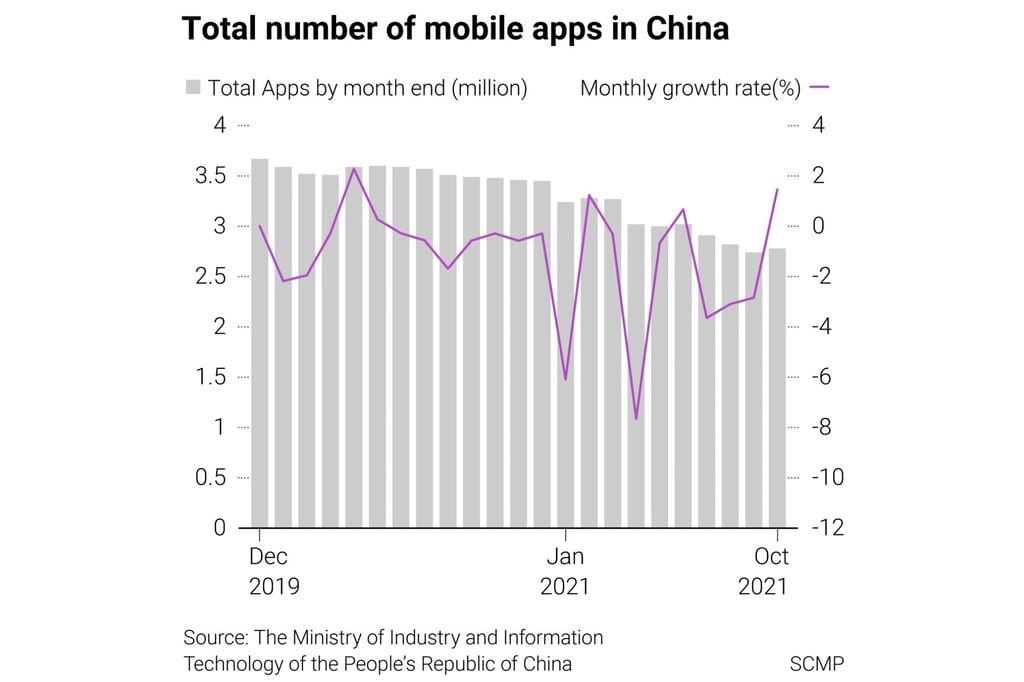

China’s Big Tech crackdown: number of apps falls 40 per cent over 3 years amid new data laws and clean-up campaigns

- Chinese app stores had just 2.78 million apps in October, down from 4.52 million in December 2018

- The biggest declines came this year, as Beijing clamped down on Big Tech platforms and introduced new data and privacy laws

Chinese smartphone users have seen the number of apps available to them fall by 38.5 per cent over the past three years, with the most precipitous drop coming this year amid the country’s crackdowns on Big Tech platforms and internet content, showing how China’s fortified market structure has taken a toll on the digital sector.

The total number of apps in Chinese app stores fell to just 2.78 million by October of this year, down from 4.52 million at the end of 2018, according to a South China Morning Post review of data compiled from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT).

Leon Sun Qiyuan, an analyst at investment research firm EqualOcean, said China’s online service market of 1 billion users is no longer a greenfield up for grabs. “China’s internet industry has developed for so many years, and the days of tremendous growth are over,” he said.

However, the change also reflects a more difficult regulatory environment, in which the app decline accelerated last spring. While the market for apps has matured globally, Google Play and Apple’s App Store have seen the number of apps they offer globally grow during the same period. While Google removed about a million apps in the middle of 2018 due to a change in company policy, the number available grew 7.6 per cent to nearly 2.8 million from December 2018 to September of this year, according to data compiled from Google by Statista.

In China, the number of apps available fell by about 850,000 over the course of 2019, when Beijing initiated a 12-month campaign in January cracking down on the irregular collection of personal information. The campaign – jointly conducted by the MIIT, Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), Ministry of Public Security and State Administration for Market Regulation – was the government’s first major review of apps.