Blockchain-based logistics looks increasingly Chinese after exit of Maersk, but Hong Kong’s GSBN has global ambitions

- Hong Kong-based Global Shipping Business Network has the largest blockchain platform for collaboration in shipping and logistics after TradeLens closure

- Blockchain has yet to catch on in the industry, but GSBN founder Bertrand Chen said it could take another decade amid further industry digitisation

Then another bombshell came a couple of weeks later, when Maersk and IBM announced they were discontinuing the TradeLens blockchain network.

Supply chain and logistics management was supposed to be one of the more revolutionary use cases of blockchain outside cryptocurrencies – proof that the technology was more than just hype and speculation. The dissolution of TradeLens threw that narrative into doubt.

Hong Kong-based Global Shipping Business Network (GSBN) now operates the largest platform that could be described a TradeLens alternative, and it says that a blockchain-based future is still coming, it just might take another decade.

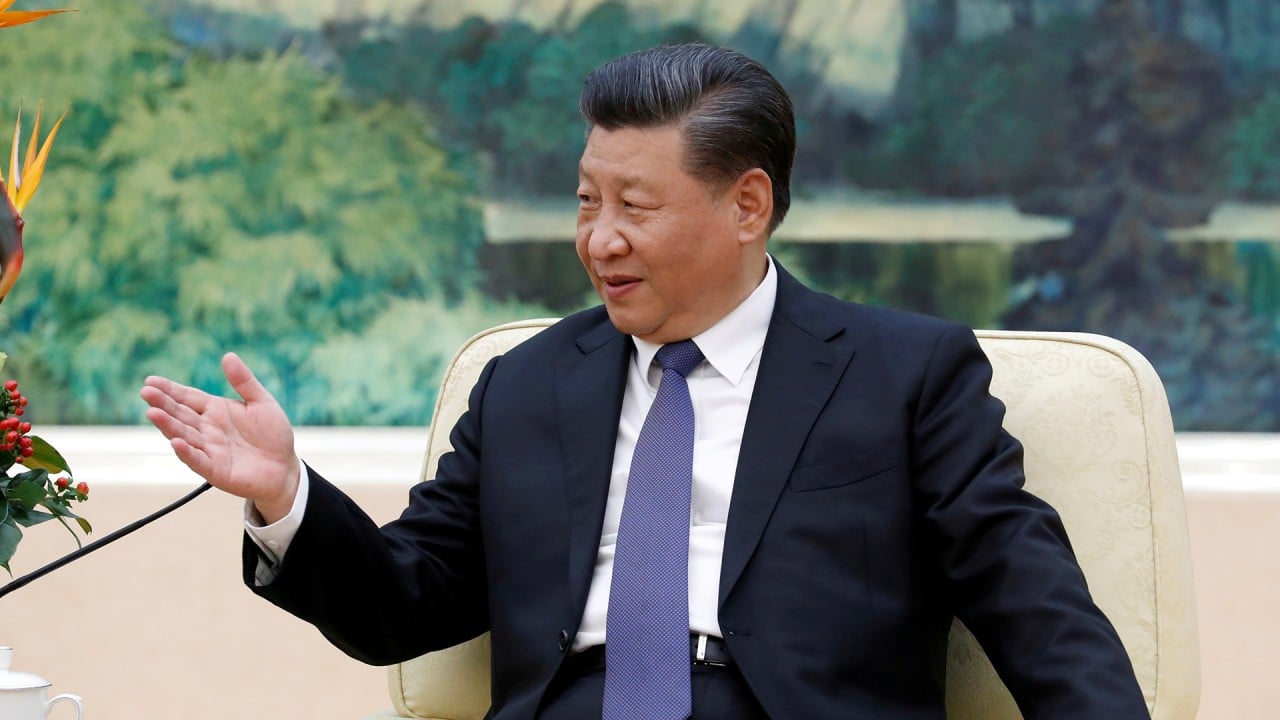

“I think for a lot of people, the clear understanding is this industry has digitised,” GSBN CEO Bertrand Chen told the South China Morning Post in December, soon after TradeLens’ closure. “There’s just no way 10 years down the road in 2032, global trade is still using pen and paper. There’s no way after Covid-19. It just cannot be.”

GSBN is a non-profit organisation with eight shareholders, each with equal voting rights on the governance of the blockchain. The members include the shipping companies Cosco, OOCL and Hapag-Lloyd, and five terminal operators – Hutchison Ports, SPG Qingdao Port, PSA International, Shanghai International Port Group and Cosco Shipping Ports.

Only Hapag-Lloyd and PSA International, which are German and Singaporean, respectively, are not based in mainland China or Hong Kong. With GSBN now operating the largest blockchain platform for collaboration in the shipping industry, the Web3 future of supply chains looks largely Chinese.

Why China is investing heavily in blockchain

Chen said in an earlier interview in November that China was taking a lead in this area because it was pouring money into the industry, but he acknowledged that many of the solutions so far are highly specific to the country, creating links between provinces or blockchains that operate in a single location.

“When you throw so much money in one sector because it’s a policy, you’re bound potentially to be able to get lucky,” Chen said. He added that China’s investment in this area would benefit GSBN by creating more partners for the company to work with.

But GSBN also has global ambitions. Chen said the company is working to attract more European shipping lines and even hopes to get Maersk on board some day, although he acknowledged that “may be slightly challenging”.

While GSBN is now the largest player, it is far from the only company trying to make blockchain happen in the industry. Some smaller data platforms like New Zealand-based TradeWindow use blockchain but have played down the technology’s role in marketing materials. Several of the biggest names in logistics have touted their own blockchain solutions only to gain little traction.

“If one company wants to do blockchain, it’s almost impossible,” Chen said. “Why do you need a blockchain as one company?”

Many in the industry agree there are huge cost- and time-saving incentives to digitise documents and processes involved in moving freight across borders. But the industry is so fragmented that agreement on new technologies and standards can be elusive.

“When we’re talking about trade documents, and the value proposition of reducing the volume of paper being used in paper transactions, there is certainly a cost saving benefit,” said Goh Puay Guan, an associate professor of supply chain at the National University of Singapore Business School. “Of course the challenge is getting all companies on board, because only when you have an integrated platform then companies actually benefit from that integration.”

For Chen and many others, the real failing of TradeLens was not the value proposition of blockchain but that it was seen as a product of Maersk, a potential competitor to other users of the platform.

“The fact that TradeLens was seeded by Maersk, from a business perspective, it was an impediment to growth,” Chen said. “Because some of the customers that they need to court say, ‘I don’t trust Maersk’.”

Chen added that he does not believe there was a real risk to user data, and there is no sign that Maersk used or could have used data on TradeLens for some competitive advantage. Still, many people have noted that this negative perception could have hurt adoption.

After the announcement of TradeLens’ closure, people on LinkedIn and in other professional spheres chimed in on where they think the platform went wrong. Many agreed that the problem was not blockchain-specific.

In one LinkedIn post that gained widespread attention, David Ziyang Fan, head of digital trade at the World Economic Forum (WEF), said that building trust is difficult, but the trend of digitisation is irreversible.

“[The WEF has] always taken a quite balanced view of what blockchain can do for the industry. We’re optimistic, but we’re definitely not blockchain maximalists,” Fan said in a video chat in December. “I feel like the pendulum has swung too far in the other direction … ‘Crypto winter’ has directly or indirectly affected people’s confidence about enterprise blockchain, especially blockchain in the trade and supply chain space.”

One of the big questions that remains around blockchain is how much it is really needed in many of the applications to which it is applied. In a LinkedIn post in December, Chen wrote that “TradeLens Core (the visibility solution) … did not require blockchain to work”.

In fact, tracing goods has existed for decades through the use of technology like bar codes, which has further improved with the use of newer chips and sensors. And transparency has increased in recent years through a variety of custom cloud platforms.

Smart Warehousing, a domestic logistics solutions provider in the US that provides product tracking in its facilities, has so far avoided getting into blockchain because its proprietary platform Swims has proven flexible enough to solve its problems, executives say.

“There are global standards for bar codes. You would have to have a global standard put in place that this is how this information is going to be passed, and here’s the formats it’s going to be passed through,” said Beth Ward, chief operations officer at Smart Warehousing.

Huawei’s automated tech on full display at Tianjin Port in commercial pivot

Even when blockchain is used to track data, companies often have their own ways of sharing the data itself, which is too large to be shared directly on a distributed ledger. Some of that data might even be in an EDI format.

The one killer application that seemingly everyone in the industry can agree might be a game-changer for blockchain in logistics is an electronic bill of lading (eBL), which has recently been gaining traction. The bill of lading is a critical document for proving receipt of goods. It remains mostly paper-based across the industry, with shippers requiring the original document to be able to transport goods.

“Because of Covid-19, because you have to change the process, I think this is one of the regular use cases of blockchain,” Chen said. “Probably that’s better than NFTs of digital art. NFTs of documents for global trade – this will be the real killer use case.”

Web3 is confused for crypto, NFTs and the metaverse, but what is it really?

GSBN facilitated the first use of a blockchain-based eBL for bulk shipping in collaboration with Cosco in January. It was issued to Brazil-based paper pulp maker Eldorado. GSBN also signed a memorandum of understanding at the end of March with Saudi Basic Industries Corp (Sabic), Cosco Shipping, Hutchison Ports and PSA International, with all agreeing to use eBLs in the future.

While eBLs have existed in some form since 1999, legal complexities and a lack of standardisation have slowed adoption. With other tools available for digitisation, blockchain could slowly be integrated into other processes in ways that make it less visible. This removes much of the hype around the technology, but it makes its use more practical and sustainable.

“In my view, blockchain has been and is still a tool in the tech stack for digitising trade,” said the WEF’s Fan. “It has always been that case.”