Tech war: Biden’s decree zaps lucrative investments in China’s chip and AI sectors

- Experts say US investment restrictions are final nail in the coffin for foreign investment into sectors such as chips and AI in China

- Some say local yuan funds cannot make up for loss of US dollar funds, which typically have long investment horizons and high-risk tolerance

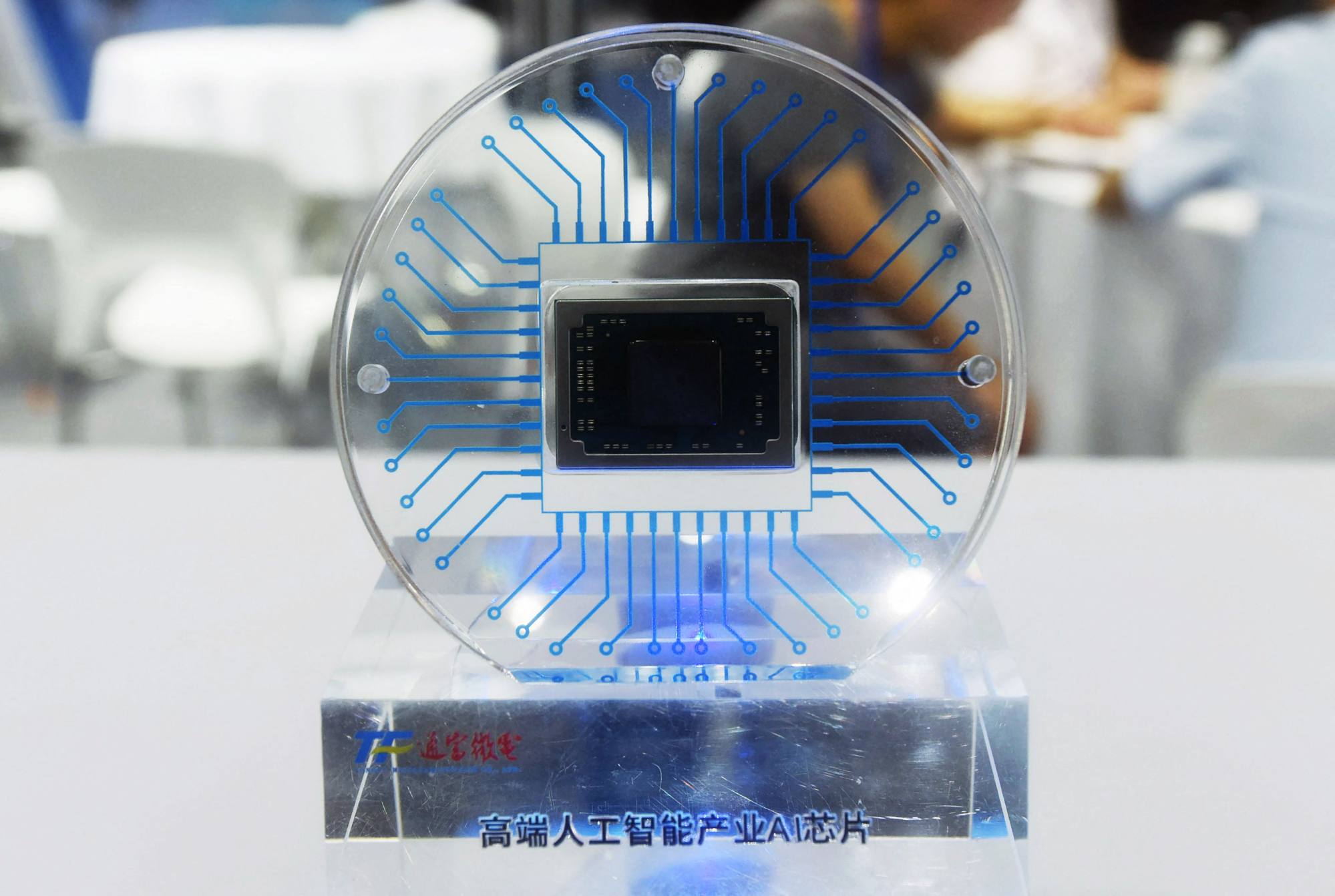

It is most likely that China’s largest chip foundry, a key piece of the puzzle in Beijing’s efforts to achieve greater self-sufficiency in semiconductors, would not have been able to set up its first plant in Shanghai’s suburbs in the early 2000s without funding from American investors such as Walden International and Goldman Sachs.

Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp (SMIC) is just one of many Chinese firms that received US venture capital funding from investors seeking extraordinary returns from China’s economic take-off, a bold example of the marriage of domestic technological ambition with adventurous American funds.

However, amid rising geopolitical tensions between the world’s two biggest economies and the implementation of tough US investment curbs, prospects for such collaboration in future have dimmed, dealing a direct blow to China’s ambitions to become a global power in artificial intelligence (AI). Industry insiders and analysts say the withdrawal of financial support and technical expertise is a game-changer.

“The damage is done in the sense that a lot of people will be scared away from the China market”, said Ben Harburg, managing partner at MSA Capital, a Beijing-based venture capital fund. “We will avoid sectors that we think are at risk or may fall foul of current or future US sanctions,” said Harburg in a recent interview with the Post.

MSA Capital manages US dollar funds with capital from sovereign wealth funds, international asset managers and pension funds, as well as Chinese entrepreneurs.

With more investors like MSA Capital trying to dodge the sanctions bullet, the backers of these funds will also have to rethink their China strategies given rising geopolitical acrimony.

Elton Jiang, founding partner at Shanghai-based Genilink Capital which backs chip start-up Black Sesame Technologies among others, said American investors will not only stop putting money into certain sectors but may also divest from companies in existing portfolios to comply with new restrictions.

Jiang added that the biggest disruption from new investment restrictions will be the deterrence factor for potential investors in China.

While US dollar limited partners (LPs) – the investors who back venture funds without being involved in day-to-day management – come from all over the world, including America, the Middle East and Southeast Asia, “historically LPs from the US account for the most significant share of all types of dollar LPs,” said Jiang. “The investment restrictions will make the LPs have second thoughts about allocating any money to China.”

In August, the Biden administration unveiled an executive order aimed at restricting US venture capital and private equity investments in Chinese companies involved in semiconductors, microelectronics, quantum technologies and AI systems.

Washington’s move to screen outbound investments came as American venture capital money was already drying up in the Chinese market, according to analysts at independent market research firm Rhodium Group. Its data shows that US backing of China start-ups plunged to a 10-year-low last year to US$1.27 billion, well down from a peak of US$14.4 billion in 2018.

While the tougher restrictions were largely anticipated by the global investment community, practitioners said that the announcement has been the final nail in the coffin for investment in the sanctioned sectors.

Tighter US chip export controls on China will mean ‘permanent’ loss: Nvidia

Kaidi Gao, an analyst at investment data service Pitchbook, said some of the largest LPs – such as pension funds on the private equity side – have now pulled back completely from fresh investment in China.

A recent report by investment research firm Preqin showed that China-focused VC funds raised US$2.7 billion from April to June, a plunge of 54.2 per cent from the previous quarter. Meanwhile, for sectors like semiconductors, funding has long been migrating to local yuan funds, according to local industry experts.

The Chinese founder of a memory controller chip design firm, who asked not to be identified due to the sensitivity of the matter, told the Post on his return from a fundraising trip, that many small Chinese chip start-ups aim to supply state-backed companies when their products are ready or they go public on the mainland’s tech-heavy STAR market. In this situation, “taking US money would send a bad signal in either case”, he said.

That comment echoes remarks made at the 2023 China Semiconductor Equipment Annual Conference (CSEAC) earlier this month, where an investor from venture capital fund Fountain Bridge Capital said they have long separated US funds and yuan funds for investment targets in China’s semiconductor industry, with the latter the only way to currently invest in the sector.

The semiconductor sector has always been a special case, with long investment horizons and high risks due to its asset-heavy profile.

The sector used to be shunned by private money until China’s self-sufficiency drive intensified due to increased tensions with Washington. Many Chinese private equity and venture capital funds were seen chasing executives at CSEAC to talk about investment opportunities.

To date the state-backed China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, also known as the Big Fund, has been the main vehicle for the Chinese government to pump money into the chip sector. The first phase of the fund raised US$19.7 billion with the second raising about US$30 billion, and it has made multiple bets on Chinese semiconductor companies since its creation in September 2014.

It is difficult to estimate the overall subsidy package extended by Beijing and local governments to the domestic chip industry, as many forms of grants are not necessarily handed out in cash terms.

Softbank-backed Arm warns of ‘significant’ China risk in its IPO prospectus

The memory controller chip founder said the city government of Zhengzhou, capital of central Henan province, wants to have skin in the game by providing cheap land parcels, factory facilities and even by paying for some equipment rather than through direct investments, as some of their financial vehicles have been damaged by China’s patchy economy.

However, for some industry practitioners, local yuan funding can never make up for the loss of US dollar funds, which typically have a long investment maturity and high-risk tolerance.

One Shanghai-based investor, who also requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of the topic, said a strength of US dollar funds is their ability to back high-risk projects, setting them apart from many yuan funds that take money from so-called government guidance funds, which are typically more risk averse. Local currency funds are less likely to invest in early projects with no income, added the investor.

In a recent round-table discussion, Duane Kuang Ziping, founding and managing partner at China-based Qiming Venture Partners, said US dollar funds have a preference for risky projects that have the potential to generate outsized returns.

Kuang also said that despite the current ChatGPT frenzy in China – which has seen local firms rush to compete with OpenAI’s breakthrough generative AI product, RMB funds would never have backed a research lab like OpenAI in the first place. This is because yuan funds will not take a risk if the development pattern and growth path are not already clear, he said.

With tougher US investment restrictions now in place, this poses a particular problem for those Chinese start-ups looking to replicate or exceed OpenAI’s success with its ChatGPT chatbot, which can provide human-like responses to user questions.

The Shanghai-based investor said although the hype surrounding China’s generative AI sector is still gathering steam, there are fundamental obstacles to turning a potential ChatGPT competitor into a profitable business.

China to make steady progress in chip equipment self-sufficiency: UBS

The last batch of Chinese AI giants, such as SenseTime and Megvii, had a sizeable share of revenue coming from government orders or subsidies. But the Chinese government has not shown an equal amount of love for the generative AI sector, which will also be subject to the country’s strict online censorship regime.

To date, all domestically-developed AI chat bots are still in the public testing phase, and no company has yet been given the green light to roll out their products to the public on a commercial basis.

On the business side, companies have been beta-testing their AI bots in traditional industries to improve efficiency and lower costs. But the financial case has yet to be proven.

iFlyTek, a Chinese AI firm that said it had surpassed the capacity of OpenAI’s ChatGPT in October, saw its net income fall 74 per cent in the first half from a year earlier. The revenue plunge came months after the Anhui, Hefei-based company launched its ChatGPT-like bot SparkDesk in early May, trumpeting its integration into a wide range of traditional industries.

Baidu, which unveiled its Ernie Bot earlier this year, had a strong second quarter with revenue growth of 15 per cent, but financial details related to its generative AI efforts are scant.

Co-founder, chairman and CEO Robin Li Yanhong said in the earnings call that generative AI “holds immense transformative power in numerous industries, presenting a significant market opportunity” for the company, without disclosing how much revenue it has made from the service.

Despite the hazy financials, generative AI remains a hot sector for investors.

“The AI leaders are mainly in China and the US … where the technologies are mostly being created and the leading companies are going to be,” said Jeffrey Towson, a partner at research firm TechMoat Consulting. “There is a lot of capital in the world. But only two big epicentres for AI.”

But as the geopolitical storm continues to gather for US investors in China, it seems increasingly likely that they will steer clear.

Long-time SMIC investor Walden International has watched as the foundry delisted from the New York Stock Exchange in 2019 after 15 years of trading and floated its shares in Shanghai the following year.

The Big Fund and local firms such as Datang Telecom Technology as well as China Information and Communication Technology Group among other state-affiliated firms, have since emerged as some of SMIC’s biggest backers, according to the company’s latest annual report.

Meanwhile, the San Francisco-based firm has just received a letter from the House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party expressing “serious concern” and probing its investments in Chinese tech start-ups.